Karl Henrik Johansson

Professor of Networked Control

Wallenberg Scholar

University:

The Royal Institute of Technology (KTH)

Research field:

Networked control systems.

Wallenberg Scholar

University:

The Royal Institute of Technology (KTH)

Research field:

Networked control systems.

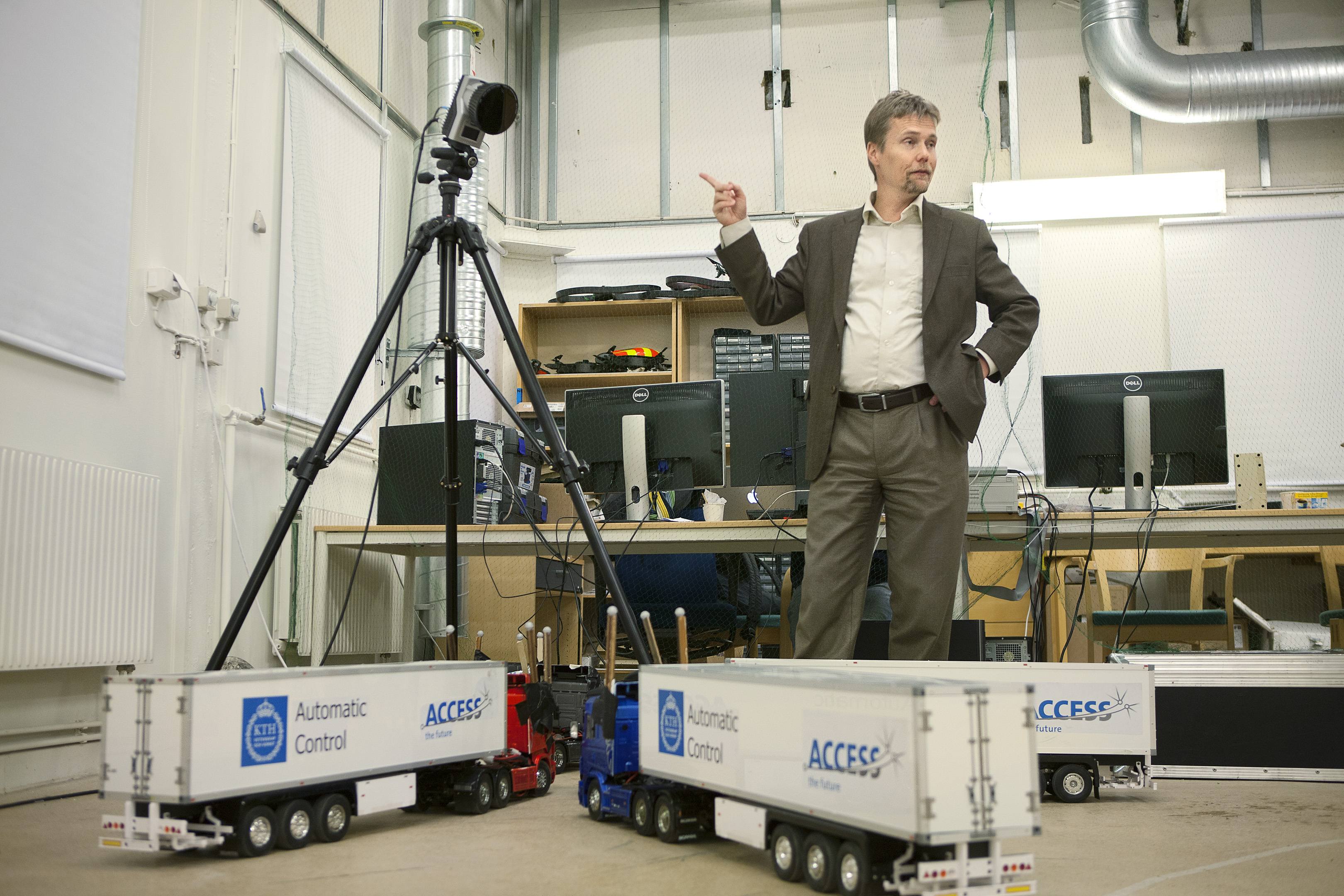

A group of radio-controlled model trucks stand waiting in the experimental lab. The high ceiling, the exposed ventilation ducts and the concrete floors with bare patches where the paint has been worn away make it feel a little like a warehouse. Karl Henrik Johansson, Professor of Networked Control, has just moved the practical parts of his activities here. A few hundred meters away, on KTH Royal Institute of Technology’s main campus, lies the department where he and his research team are developing new theory in networked control: how different devices can collaborate to solve a common task. The trucks mentioned earlier are being used to work out how they can communicate to drive close to each other without colliding. The vehicle at the front must have a driver but the others follow along behind automatically at a distance of only some tens of meters. The closer they are together, the less the air drag and the greater the fuel savings.

– Freight transportation worldwide is expected to increase by 50% between 2000 and 2020. If we group trucks into convoys or platoons so that they travel together we can save 5-10% of the fuel, says Karl Henrik Johansson, a Wallenberg Scholar since 2009.

Scania is already using his technology on the roads. The company has a haulage business where they among other things are testing platoons of 3-4 trucks at a time between Stockholm and Zwolle in Holland. But here at KTH the technology will be refined still further. The vehicles must be even better at collaborating, shipments must be transported at set times and the road network must be utilized more efficiently. The model trucks and other vehicles in the lab are equipped with micro-computers, sensors and wireless communication.

– If the trucks are to drive at a certain distance from each other they must be able to communicate. The trucks that are following must be able to adapt quickly when the one in front brakes or accelerates, Karl Henrik Johansson goes on.

The trucks are in effect mobile sensors that know where they are and can receive and communicate information about road conditions and other traffic. Using infra-red cameras the team of researchers have set up an indoor GPS system in the former warehouse. It’s the same kind of system film-makers use when they animate characters like Gollum in Lord of the Rings. The team intend to project the road network onto the floor and the idea is for the map to roll along to allow the model trucks to drive around the whole of Europe in a space that measures only 10 by 15 meters.

As far as Karl Henrik Johansson is concerned, the truck experiments are about more than just fuel consumption. He sees the trucks as mobile devices in a dynamic network, where each device is dependent to a greater or lesser degree on all the others. When the devices communicate they can adapt to each other and benefit from one another’s information. Devices or systems do not necessarily have to be trucks; they could also for example be rooms in a building or interconnected processes in industry.

– We develop basic theories for designing interconnected systems, says Karl Henrik Johansson.

The team devise equations that describe the systems’ communication and program computers to control and optimize the processes automatically. The research field is called “networked control”. Karl Henrik Johansson takes another example: washing machines developed for the Stockholm Royal Seaport, an ecodistrict currently being built in Stockholm. The washing machines, developed by Electrolux, sense transient peaks in power consumption and act accordingly. Automatic adaptation like this evens out the load on the power grid.

− One machine makes no difference, but when all the households in the Royal Seaport, or all of Stockholm, do their washing like this it suddenly makes a big difference, explains Karl Henrik Johansson.

When he applies his theories it is often a matter of small changes that lead to substantial energy savings; simple yet smart innovations that make things more efficient. A doctoral student has recently begun experimenting with KTH’s energy use and wants to connect temperature regulation to the university’s teaching schedules. An empty lecture room must use a minimum of energy and heating and ventilation will not be turned on until an hour before students arrive.

But Karl Henrik Johansson also has some wilder visions. On a shelf in his lab stand some model that look like helicopters. With the help of dynamic network control these will fly in formation around the warehouse. The helicopters will sense and adapt to each other and the traffic on the floor – fully automatically. He hopes to be able to invite school pupils to come and try them out and be inspired by the spectacular technology. So it’s a good thing that there’s also room for fun inside Karl Henrik Johansson’s lab.

“Thanks to the long-term funding that a Wallenberg Scholar award brings, I can approach some of the biggest and most important research problems in my field. The award is also an acknowledgement that the research I lead is at the international forefront and important to Sweden, which makes it easier for me to recruit doctoral students and researchers.”

Text Ann Fernholm

Photo Magnus Bergström