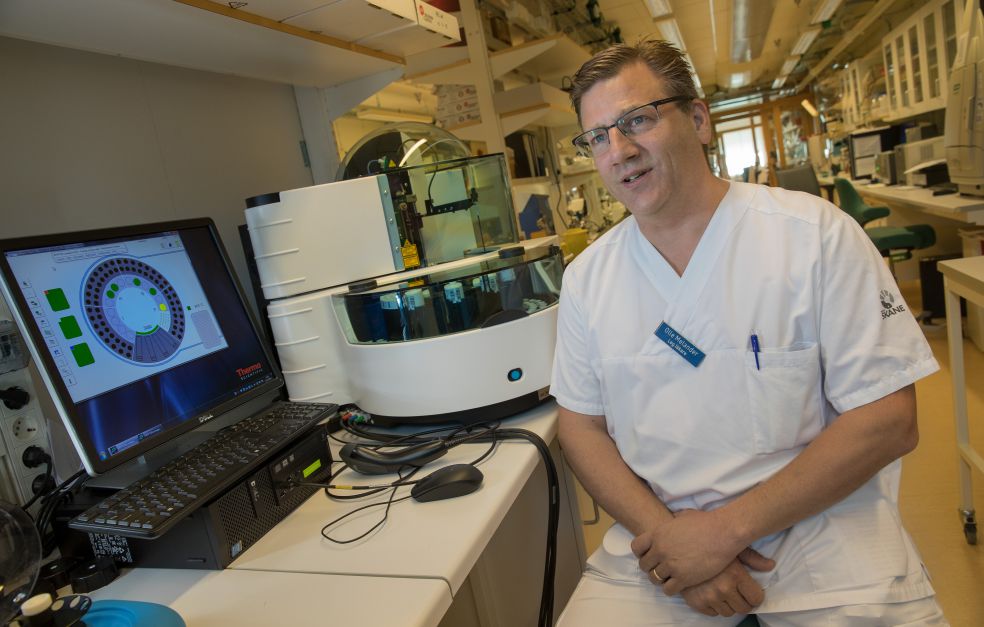

Many people live without knowing they run a risk of suffering from serious diseases. They have no known risk factors, but nonetheless develop cardiovascular diseases or serious kidney disease. If they could be identified and helped in time, thousands of people could be spared suffering and premature death. Olle Melander at Lund University is looking for new tests and preventive therapies.

Olle Melander

Professor of Internal Medicine, specializing in cardiovascular diseases

Wallenberg Clinical Scholar 2016

Institution:

Lund University

Research field:

Multidisease – risk factors and prevention

Smoking, obesity, high blood pressure, high levels of blood fats and blood sugar. These are some of the known risk factors for cardiovascular disease, diabetes and kidney diseases.

“But half of people hospitalized following a heart attack are theoretically in the low-risk category. If we’d met the person three months earlier and measured the risk factors we know about, we’d have said ‘no action needed’. And heart attack patients are only one example. So there is room for improvement,” says Melander.

He is Professor of Internal Medicine at Lund University, and a doctor at Skåne University Hospital in Malmö. As a Wallenberg Clinical Scholar, he will be examining new ways of measuring the risk of disease using simple blood samples. He also wants to identify preventive steps that can be taken before the disease strikes.

Melander describes internal medicine as taking care of patients suffering from several diseases at the same time. There are often good treatments available for a patient with diabetes alone, or narrowing of the arteries, or kidney disease. But when the same person suffers from several chronic diseases, therapies may begin to counteract one another.

“And the risk of sharply deteriorating quality of life and premature death is much greater among those suffering from several chronic diseases at the same time. These are the patients we want to identify and help even before they fall ill.”

Genes play a key role in disease

The project Melander is heading as a Wallenberg Clinical Scholar is pursuing three lines of enquiry.

One is to map in greater detail the genetics behind the diseases. The researchers may be said to be taking a back-door route; they are searching for genetic changes that appear to protect people from disease by preventing certain genes from doing their job. This gives an idea of the genes that are “disease genes”, on which preventive efforts should focus. Perhaps their activity can be inhibited with drugs, or by lifestyle changes.

Another approach also concerns genetics, but in this case the researchers know which genes they should focus on. These are the genes that code for a hormone called neurotensin. It is secreted when we eat, and drives the uptake and storage of fat from food.

“This was a great hormone to have plenty of in the Stone Age, when food was often in short supply. But in modern-day society there is often a surfeit of food. High levels of neurotensin are now a strong factor indicating a risk of early heart attack, early diabetes and premature death,” Melander explains.

“Being admitted as a Wallenberg Clinical Scholar is a pretty unique form of support, especially as it covers such a long period. It’s a career-changer. Also, there are not many funding bodies investing in clinical research. The Foundation’s support will enable me to take on long-term projects that I would never have been able to pursue otherwise.”

Genetic profile and risk hormones tested in blood samples

High levels of neurotensin are the result of multiple copies of the gene responsible for producing the hormone. People with many copies of the gene take up more fat. Melander points out that diets rich in fats and low in carbohydrates have gained in popularity in recent years, but that they are probably a bad idea for the 20 percent of the population with the highest levels of neurotensin.

One study currently in progress is examining whether high levels of neurotensin can be reduced by a low-fat diet. In another study researchers are attempting to design a drug – probably an antibody, that binds the hormone as it circulates in the blood, preventing it from doing its job. Further research aims to ascertain whether neurotensin really does cause disease, or whether it actually serves as a marker for the risk of disease, without itself being the cause.

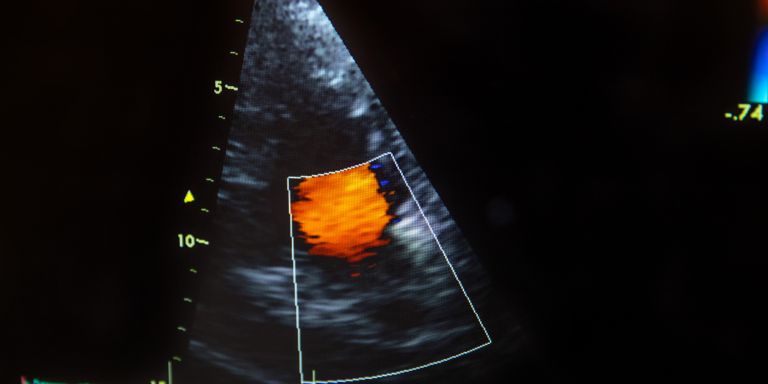

“A common goal for the whole project is to find things that can be tested in the blood - things that show whether there is a risk of disease. Genetic profile testing may be one way – high levels of certain hormones another.”

Personalized preventive therapy

The third part of the project centers on another hormone, vasopressin, which regulates the fluid balance in the body. Low fluid levels cause higher secretion of vasopressin, which retains fluid in the body. Melander and his colleagues have noticed that people living with constant high levels of vasopressin appear to run a greater risk of suffering from serious diseases. If this is so, treatment is very simple: drink more. In one study, people with high vasopressin are selected at random to either drink one-and-half liters of extra fluids every day for one year, or to drink the amount they normally do.

“There has been much discussion of how important it is for one’s health to drink enough. But roughly one-fifth of the population has high concentrations of this hormone. Other people probably drink enough as it is,” comments Melander.

He divides his time between research and his patients, some of whom are seriously ill, some living with a high risk of disease. They attend a preventive medicine clinic. Much of the research begins with observations the doctors make at the clinic.

“You can’t base everything on theory. The disease profile is so extraordinarily complicated. There is much talk of ‘personalized medicine’ nowadays. I’m sure we need the same thing in preventive health care. We must devise tests so we can measure the risk in blood, and design ‘personalized prevention’. What works for you might not work for me at all – whether it’s drugs or exercise.”

Text Lisa Kirsebom

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström