Quality of political institutions, trust, and corruption. These concepts form the basis for Wallenberg Scholar Bo Rothstein’s research. At the Quality of Government Institute, founded by Rothstein, researchers are attempting to define corruption and identify methods of combating it.

Bo Rothstein

The August Röhss Chair in Political Science

Wallenberg Scholar

Grant from Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation

Institution:

University of Gothenburg

Research field:

Quality, welfare policy, social trust, and corruption in political institutions

Oxford University Press publishes handbooks presenting the latest research in various fields. Rothstein’s colleagues at the Quality of Government Institute in Gothenburg (QOG) were recently commissioned to write such a book – a thousand-page tome on “quality of government”. New generations of researchers will get to see which methods and theories are relevant, what knowledge is available, and what gaps need to be filled.

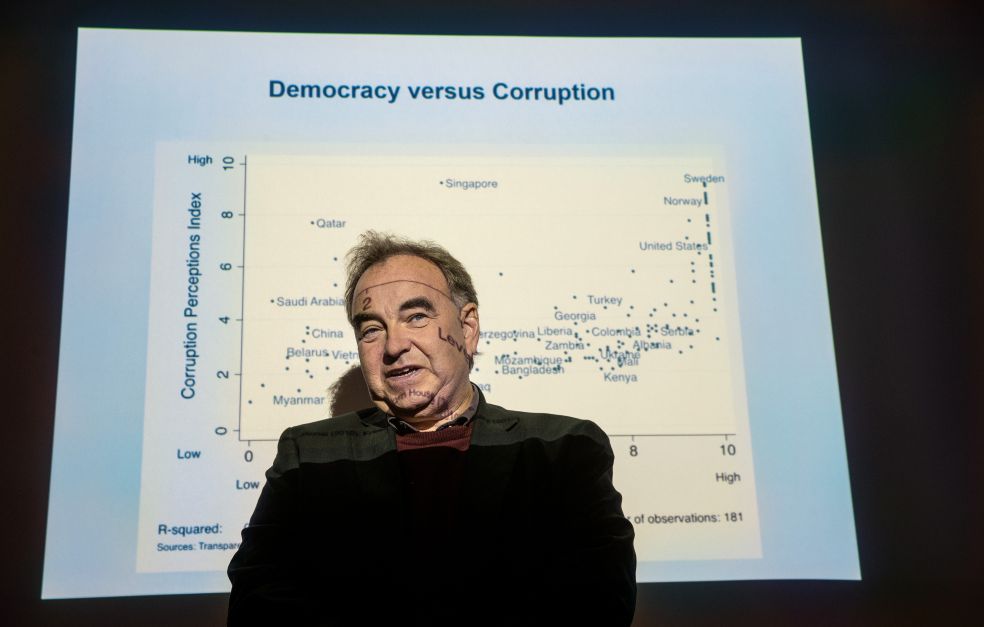

“I see an enormous interest in this kind of research. It’s very different from when we started the institute fifteen years ago, when corruption was a taboo subject,” Rothstein says.

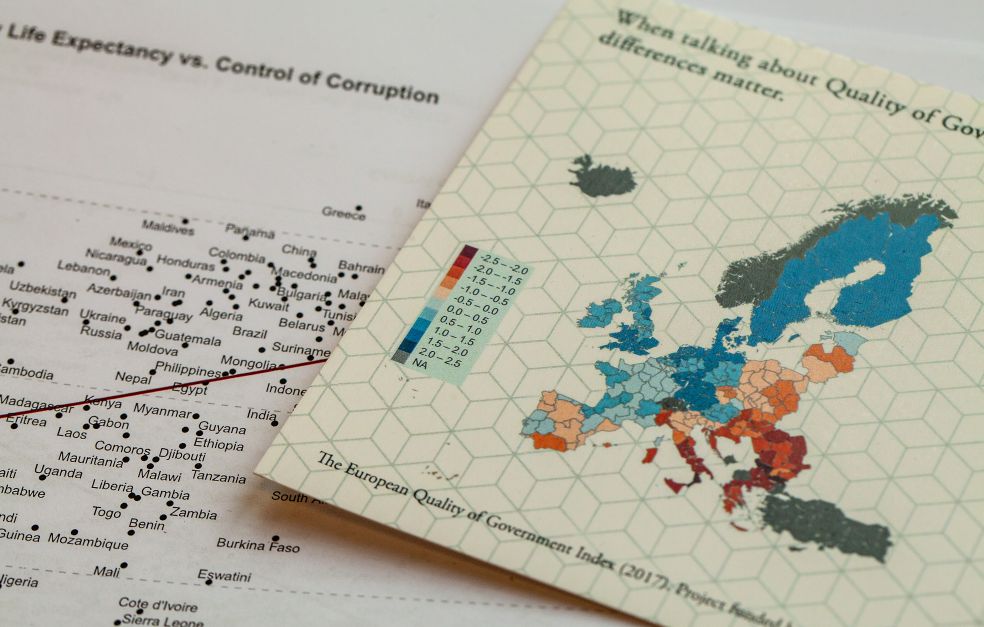

At that time there were no data on which to base empirical research. According to Rothstein, discussing corruption in developing countries was a delicate matter. It was perceived to be pointing the finger of accusation; and researchers in economics also thought that these problems would resolve themselves in a market economy.

“Many people thought that if we just leave the market alone, it will be efficient. But it’s not. Corruption occurs,” Rothstein comments.

What corruption is not

Corruption is a broad term, difficult to define. The researchers in Gothenburg decided to approach the problem from the opposite direction: What is not corruption? They attempted to define quality in political organizations. After many years of collecting statistics, in-depth interviews, and collaborating with other experts, including anthropologists, they have concluded that the most important characteristic of non-corrupt organizations is impartiality. Citizens are treated fairly and equally. When the researchers studied codes of ethics for public administration in some 30 countries around the world, they also identified impartiality as a recurring theme. It seems to be a universally accepted norm for good public administration.

Other inferences drawn are that corruption is less prevalent in administrations based on meritocracy, i.e. that the person best suited for the job should be appointed (rather than someone who is related to someone, or is able to pay), and that there is less corruption with a higher proportion of women in decision-making roles.

“It’s not really all that surprising. Over ninety percent of criminals serving time in prisons across the world are men. Corruption is usually illegal, so why shouldn’t we see the same trend here? Whether it’s due to heredity or environment is a complicated issue – as a social scientist, I can’t really provide the answer,” Rothstein says.

He sees corruption becoming an ever more pressing issue on the international agenda. Rothstein considers that many of today’s popular protests have more to do with corruption than they do with traditional dimensions such as right- and left-wing politics or religious/non-religious politics.

Striking at the roots of corruption

QOG is also studying what is needed to come to grips with corruption, and has ruled out several strategies that do not appear to work, such as harsher punishments or more control and surveillance of officials. Rothstein has now arrived at a hypothesis linking corruption to an existing sociological theory on individual rationality and collective rationality – two phenomena that may very well conflict with each other.

“Being the only honest police officer in a Mexican police force may be pointless, possibly even dangerous. Corruption is a problem of frequency: Individuals do what they believe most other people would do. Defeating this kind of logic requires a signal, not only that you should change, but that the majority of people are in the process of changing,” Rothstein explains.

“Receiving a grant as a Wallenberg Scholar means a great deal to me and to the institute. It has enabled me to create an infrastructure, recruit researchers, and build up the databases we use in our work.”

He is now working on a book describing the nature of corruption, the factors that govern it, and is also attempting to suggest a way of defeating it. He believes in an indirect strategy: not attacking corruption itself, but striking at the premises on which it is based. These include what is usually referred to as a “broken social contract”. When the state does not deliver the things it should, such as security, education and infrastructure, people do what they need to do to safeguard their own position. They become less willing to pay tax, and therefore care less about how the powers that be spend tax revenues or the foreign aid budget. Thus, to counter corruption, the state needs to establish an effective social contract that creates trust and engagement in how society is governed.

When Bo Rothstein is not writing books and scientific articles, his op-ed articles can often be seen in the daily newspapers. He sees it as a researcher’s duty to contribute to public debate in various ways.

“I have the enormous privilege of having had my research publicly funded or, as now, privately funded by a public foundation such as Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation. If I discover something of importance to society – I think it would be unconscionable not to make my findings known. And given that it usually takes at least three years from discovery to scientific publication, it’s quite gratifying to write something on a Thursday and see it published in the newspaper on Monday. But not all academics like to be in the public eye. It naturally depends to some extent on what kind of person you are.”

Text Lisa Kirsebom

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström