Researcher Lars Nyberg in the northern Swedish city of Umeå is using MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) to study how the brain works. Among other things, his findings reveal a link between physical activity and a good memory.

Lars Nyberg

Professor of Neuroscience

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Umeå University

Research field:

Longitudinal mapping of memory and cognition in relation to the structure, function and dopamine system of the brain.

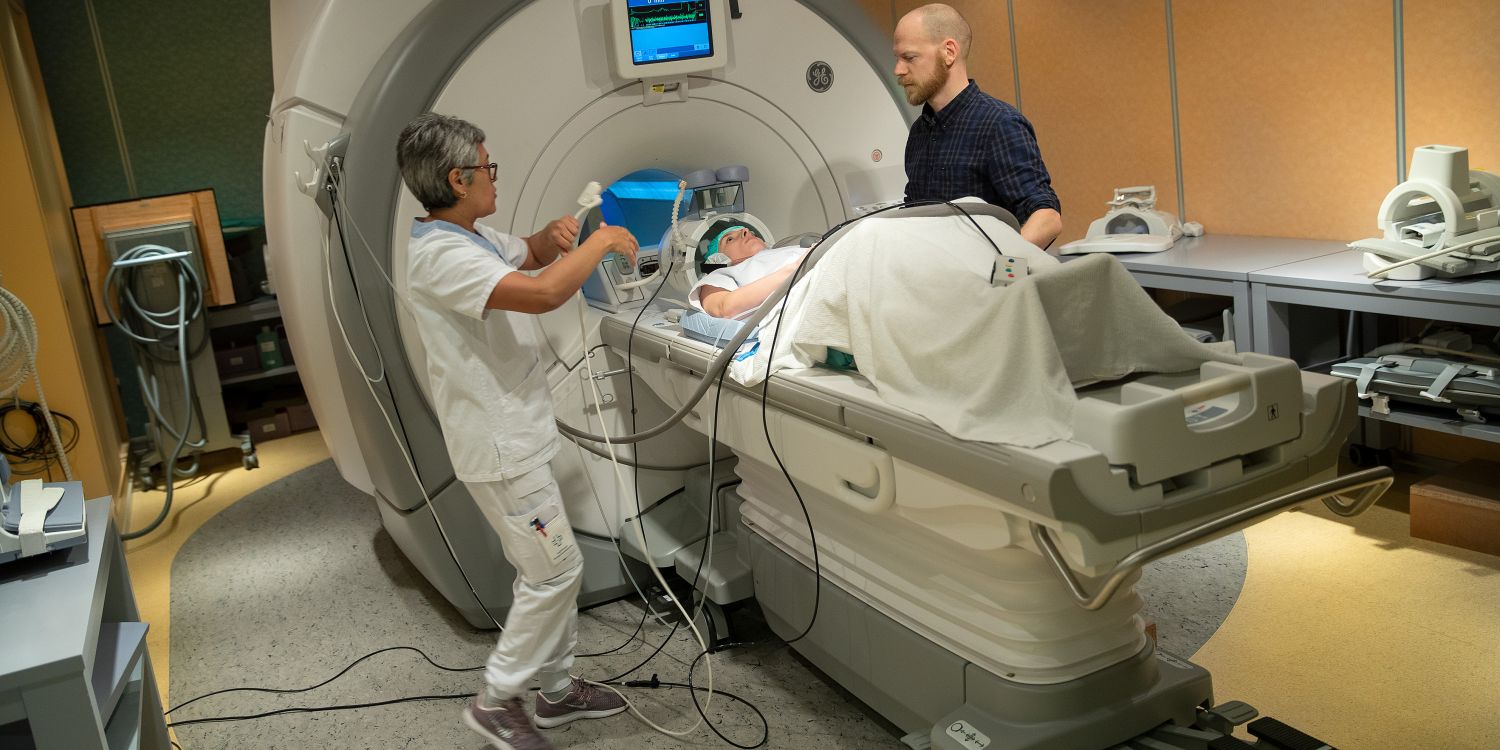

Nyberg is standing and waiting in the room outside the MRI facility one floor down from the Main Hall at the University Hospital of Umeå. We have a look at the huge machine through an open door, taking care not to step over the threshold. It is not a good idea to get too close to the strong magnetic field before discarding mobile phones, hair slides, and anything else containing metal.

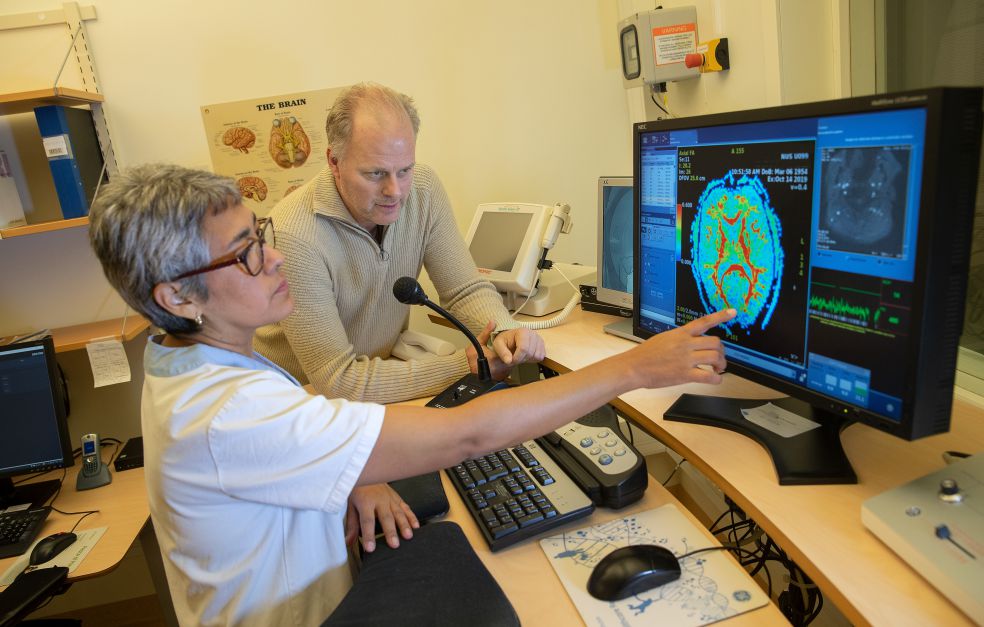

MRI is a radiological method being used by Nyberg and his research team to study ageing of the brain. Among other things, the scanner can be used to see how activity changes in different parts of the brain when we use it to remember or focus our attention on something.

Changes over time

Nyberg heads Umeå Center for Functional Brain Imaging (UFBI), and is leading two studies using various new technologies to examine the brain and memory. In one project, called Betula, which has been running since 1988, participants have been tested, interviewed and examined medically and psychologically. In recent years they have also undergone MRI scans. The tests are repeated at regular intervals over many years, to show changes in individuals over time.

“Longitudinal studies are costly and time-consuming, but provide unique information about long-term processes,” Nyberg explains.

Another project – Cobra – is studying the brain’s dopamine system in collaboration with Karolinska Institutet in Solna, north of Stockholm, and the Max Planck Institute in Berlin. Dopamine is a signal substance that plays a major role in memory and other intellectual functions. It is measured using the PET imaging technique (positron-emission tomography).

Betula and Cobra are also evaluating the extent to which the brain’s intellectual functions are affected by hereditary characteristics, social interaction and physical activity.

“We hope to obtain unique information on links between the structure of the brain and its function, as well as intellectual capacity, and how changes in the brain can explain why some people, but not all, experience cognitive impairment over time,” says Nyberg.

The hippocampus, located in the temporal lobes, plays a central part in episodic memory of events and experiences. These are memories that fade over time.

Semantic memory (our memory of facts) is not affected to the same extent. Some studies suggest that it might even improve up to a fairly advanced age.

A connection between the brain and its structure is one of many discoveries that have already been published. Memory deteriorates if the brain shrinks, i.e. atrophies.

“The brain is plastic. It can change. We have gone on to analyze various sub-groups that experience rapid deterioration or whose memory remains good,” comments Nyberg.

“Long-term funding means a great deal to a researcher. Every funding application that I don’t have to make gives me more time for research. That’s how I want to spend my time.”

Major individual differences

The Betula study has also shown that memory function remains fairly stable until people reach their sixties. There are also seventy-year-olds whose memory is as good as someone in their thirties. So there is great variation from one individual to another.

“We’ve managed to link good brain functions to hereditary factors, and in some cases to specific genes, and a specific lifestyle, such as regular physical activity.”

Being surrounded by family and close friends is another healthy factor. Daily conversations about events in the local surroundings, and in the wider world, help to keep the brain in shape: “Have you been following what’s going on with Boris Johnson? And where did Greta Thunberg give her latest speech – was it in Madrid?”

“We need someone to share our thoughts with. It gives our memory the daily training it needs.”

The researchers want to find a systematic method of training memory, and to this end have developed an app in collaboration with Swedish National Memory Team. Hundreds of participants have downloaded the app to take part in tests and evaluations over a three-month period.

Nyberg is a little worried that employers do not always value older employees. Some people are physically worn out when they reach retirement age; others are able to continue working, and can contribute know-how and abilities that are still intact, and that may even increase over time.

“We continue to build our semantic memory and analytical capacity. It would be a huge waste if society didn’t make use of these assets.”

In his own field, he has seen how professors are obliged to retire and leave the academic world.

“I think we’re starting to see a change for the better, with special positions being offered to senior professors. It doesn’t have to be at the expense of the next generation. I think that the young and old can co-exist.”

Trained as psychologist

Nyberg trained as a psychologist, and received his PhD in 1993, with a thesis on memory phenomena. As a postdoc in Canada, he became increasingly fascinated by complex functions in the frontal lobes of the cerebral cortex.

“The frontal lobes are often described as the conductor orchestrating the activities of the brain. They are intimately connected to other parts of the brain, including the hippocampus, which is central to memory functions, and are vulnerable in various diseases.”

He was appointed professor of psychology in 1999 and neuroscience in 2006. In 2009 he was chosen as a Wallenberg Scholar, and his grant from Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation has been extended for a further five years.

“Long-term funding is essential for young researchers, as well as for more senior ones. Longitudinal studies take a long time but yield results.”

Text Carin Mannberg-Zackari

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström