How does the immune system adapt to the oxygen shortage resulting from the presence of a tumor? Randall Johnson is studying the complex interaction between the individual immune cells. He sees potential for new and better cancer therapies.

Randall Johnson

Professor of Molecular Physiology and Pathology

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Research field:

Interaction and response to oxygen availability in the immune system

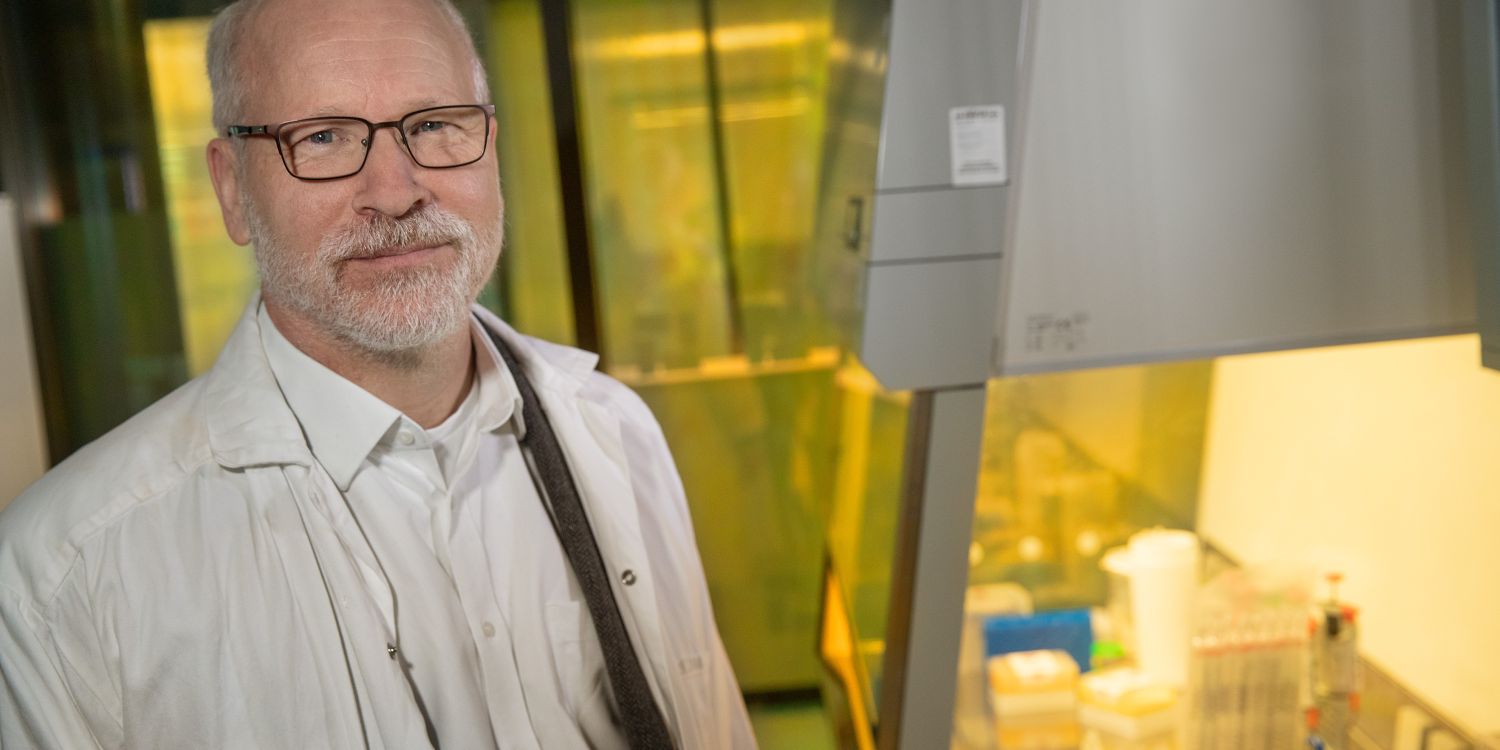

Professor Johnson meets us in the eight-story high atrium in Biomedicum, on Karolinska Institutet’s campus in Solna, north of Stockholm. The center was inaugurated only a year or so ago, and is home to one of Europe’s foremost research environments. Professor Johnson was born and bred in the U.S., but surprisingly, speaks almost perfect Swedish. The reasons can be traced back to the 19th century and Västergötland province in the south of Sweden. Of this, more later.

For many years Professor Johnson has been working to improve our understanding of how oxygen deficiency impacts our immune system. Among other things, he has demonstrated that immune cells have the ability to adapt depending on the availability of oxygen. This ability enables them to survive even in the most oxygen-deficient tumors.

“But individual immune cells are affected in different ways, and we have made strenuous efforts over the past few years to find out why,” says Professor Johnson.

Nobel Prize

The exact way that the body senses and adapts to oxygen availability was a long-standing mystery. It was not resolved until the 2000s. In 2019 the scientists behind the explanation were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. One key to the riddle was found in the HIF (hypoxia-inducible factor) protein, which helped in understanding an essential adaptive ability that our cells possess.

“This issue has engaged numerous scientists over the years, as the Nobel Prize also shows. But few researchers have looked into the relationship between oxygen availability and immune cell function,” Professor Johnson explains.

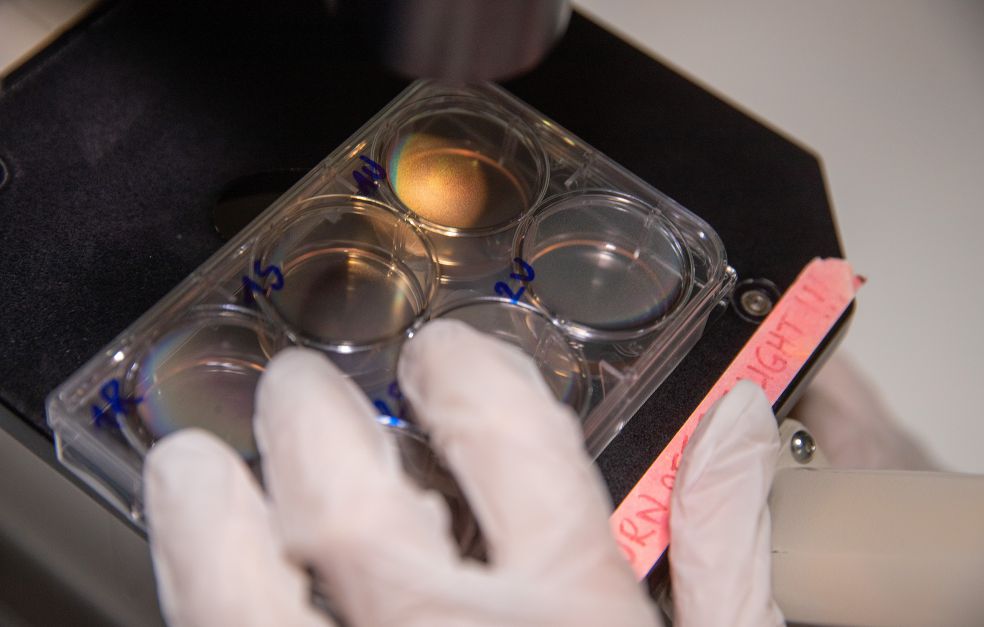

So it was a breakthrough when Professor Johnson was able to show that the HIF protein also performs a key function in the immune system. But the function has proven difficult to understand and describe. This is because the HIF protein can both activate and inhibit the immune system, depending on the kind of immune cell it regulates.

“Also – oxygen availability governs the ability of immune cells to interact with each other. We need a better understanding of the communication itself. How does it work, and how can it impact the immunotherapies currently in use?”

So far Professor Johnson has managed to show how oxygen deficiency and the HIF level impact individual immune cells. But the manner of the interaction between them remains an unanswered question.

“Our next task is to understand the big picture – piecing together the puzzle. But this is also by far the hardest part.”

This is why the five-year Scholar grant from Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation is so welcome.

“It’s a hugely generous grant from the Foundation. And the timing could not be better, now that we’re on the point of gaining a broader understanding,” Professor Johnson enthuses.

A better understanding of the interaction between different immune cells may lead to better treatment methods for cancer, and also methods of inhibiting the immune system’s reaction in the case of auto-immune diseases.

“I hope our findings will help to make future tumor therapies as effective as possible,” says Professor Johnson.

“The Scholar grant gives me the freedom to pursue new ideas to see where they will lead – the freedom to choose my own research path.”

Swedish roots

Back to Västergötland in the 1800s. Professor Johnson’s ancestors were among the million or so Swedes who emigrated in the years around 1900 to seek their fortune in the United States. He was told of his family history even as a small child.

“Although my parents didn’t speak Swedish, they kept a number of traditions alive, such as Swedish Christmas celebrations, for instance.”

So when he began his studies at the University of Washington, Seattle, he read the history of Swedish literature. He also wanted to speak the language of his ancestors. To improve his chances of success, he chose to spend a year as an exchange student at Stockholm University. Alongside his studies, he worked for SL (Greater Stockholm Public Transportation), interviewing bus passengers.

“It was those interviews that really taught me to speak Swedish. Back home in the U.S., my paternal grandfather was the only one who still spoke Swedish. When I returned from Sweden we could speak Swedish with one another, even though he spoke a very archaic form of the language, liberally sprinkled with English loan words.”

His time at the University of Washington bore fruit in the form of degrees in Swedish literature and biology. Biology took precedence when it was time to choose a career. When he was offered a position at Cambridge, England, his thoughts turned to Sweden once more. By that time he had made a name for himself in the field, and Karolinska Institutet welcomed him with open arms. And he could already speak Swedish, of course.

Nowadays he conducts most of his research at Biomedicum in Solna. He has also been a member of the Nobel Assembly since 2015.

“My role there enables me to extend my knowledge to other fields, while also helping to disseminate new research findings.”

Text Magnus Trogen Pahlén

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström