Wallenberg Academy Fellow Mikael Roll is exploring how the structure of the brain influences our linguistic ability. One unexpected finding is that a thicker cerebral cortex seems to help in understanding grammar. The research may result in new language learning methods and a new theory of how language works.

Mikael Roll

Professor of Linguistics

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, prolongation grant 2018

Institution:

Lund University

Research field:

Neurolinguistics, including interaction in the brain between different kinds of linguistic communication, such as intonation and grammar

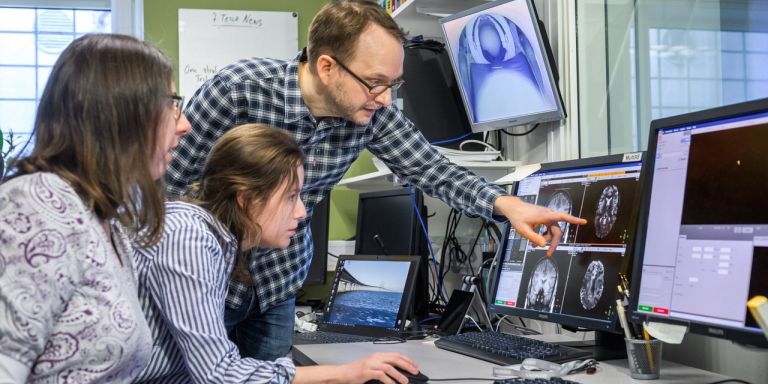

Neurolinguistics is a subject where medicine and natural sciences meet the humanities. Various imaging techniques are used to map the regions and networks in the brain that are involved in our linguistic behavior. Roll works at the Centre for Languages and Literature at Lund University.

“For me it feels natural to work in these overlapping fields. It’s exciting to establish an environment that bridges the gap between faculties. At the moment, for example, I have a person working on their doctorate in medical radiation physics – someone who is a hospital physicist and virtually a phonetician as well.”

In recent years Roll has published findings revealing how we make use of intonation to predict grammatical inflection. In Swedish the pitch used by the speaker at the beginning of a word is related to its end. Bilen (the car) has one intonation; bilar (cars) has another.

“This applies to virtually all words in Swedish; these small tonal differences say what ending the word will have. When we listen to someone talking and hear their voice, we also hear a certain tone of voice, and unconsciously use the information to predict how the word will end. This enables us to process words more quickly.”

All Swedish words ending in -en have the same tone. Bilen can be compared with bussen (the bus) and båten (the boat). It works the same way for all words ending in -ar: bilar, bussar (buses), båtar (boats).

Discovered an unknown brain signal

Using EEG to measure brain activity, Roll discovered a hitherto unknown brain signal that shows that the brain activates different ways the word might continue when we predict something. He calls the signal “preactivation negativity”.

“The more certain we are about what the person we’re listening to will say, the stronger the signal.”

Further studies have shown that we not only use tonal accents, but all kinds of language sounds to predict how words will continue.

“As soon as we hear a word, we begin to activate different potential continuations; the fewer continuations there are, the more certain we become, and the activation strengthens.”

The mechanism is particularly valuable when we talk to each other amid high background noise, as in a noisy pub, on the phone or via a video link.

Thickness of the cerebral cortex is key

Roll also uses MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) to obtain a picture of the brain’s structure in relation to activity in different areas. There have been some surprising results. The researchers have found that the structure of the brain differs in people assumed to have higher activity in the area used to process tonal variations to predict how words will end.

“The more a person uses tonal signals, the thicker the cerebral cortex is in that area.”

This unexpected discovery spurred Roll on to continue along the same lines. He is now examining more linguistic abilities to see how they correlate to the thickness of the cerebral cortex. It turns out that the cerebral cortex is thicker in a specific area in the left-hand side of the brain, known as Broca’s area. This area plays a part in how we learn and process grammar.

“We’re using a made-up language in our studies, and the thicker the subjects’ cerebral cortex in Broca’s area, the better they were at learning the artificial grammar.”

It could also be seen that the thickness of the cerebral cortex in the corresponding area in the right-hand side of the brain correlates with the subject’s ability to hear small differences in pitch.

“But there the correlation is the opposite – the thinner the cerebral cortex, the better the ability to hear the differences.”

From simple to complex abilities

The findings form the basis for a new project in which the emphasis is on the mother tongue. The hypothesis is that a thinner cerebral cortex appears to be better for simpler tasks, such as distinguishing between frequencies, and a thicker one is better for more complex abilities, such as learning grammar.

“We envision a gradient going from simple abilities to complex ones, corresponding to a gradient in thickness of the cerebral cortex.”

It may be likened to a stairway on each step of which the brain analyzes increasingly advanced information further and further forward in the brain, while the walls simultaneously become thicker.

“We can see in the primary auditory cortex how people differentiate between frequencies – a fairly simple form of processing. One step up we can see more use of differences in sounds to distinguish meaning. Then we reach syllable level, and eventually even bigger units, such as words, phrases, and so on.”

Roll’s dream is to be able to use the findings as the basis for a new theory on how language works, founded on processes in the brain and learning. The research may also be used to shed light on the progress of diseases such as Alzeimer’s, and on various brain injuries.

“Being chosen as a Wallenberg Academy Fellow is the main factor that has enabled me to establish a research team to realize our visions. The interdisciplinary network of Fellows is also fruitful and engenders discussions on interesting topics.”

Roll has also developed a language learning game, which is of interest in research, and may be of use in the school environment.

“The game is based on our findings about the prediction mechanism, and has been developed to enable people to learn the entire Swedish inflection system. But the game can be modified to enable the player to learn grammatical phenomena in many languages, and has great potential.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Kennet Ruona