People who eat too much and move too little get fat. But do they get sick? Not for sure. Mikael Rydén at Karolinska Institutet is studying how the behavior of our fat cells indicates who runs the greatest risk of obesity-related complications.

Mikael Rydén

Consultant and Professor of Clinical and Experimental Fat Tissue Research

Wallenberg Clinical Scholar 2020

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Research field:

The role played by fat cells in obesity, type 2 diabetes and other conditions

Overweight and obesity can cause type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and other complications. But not all overweight people get sick. Mikael Rydén, a consultant and Wallenberg Clinical Scholar at Karolinska Institutet, is studying white adipose (fatty) tissue (WAT) to find out why these diseases occur.

One of the key tasks of fat cells is to take up, store and release fat in line with the body’s needs. When people put on weight their fat cells change, but not in the same way in everyone. Rydén has observed this fact in the overweight patients whom he and his colleagues are monitoring at a clinical research center. Some of them have been providing samples for as long as fifteen years.

“We’re trying to find out precisely what characterizes ‘bad’ and ‘good’ adipose tissue by examining exactly how the cells work, and how they interact with other cell types.”

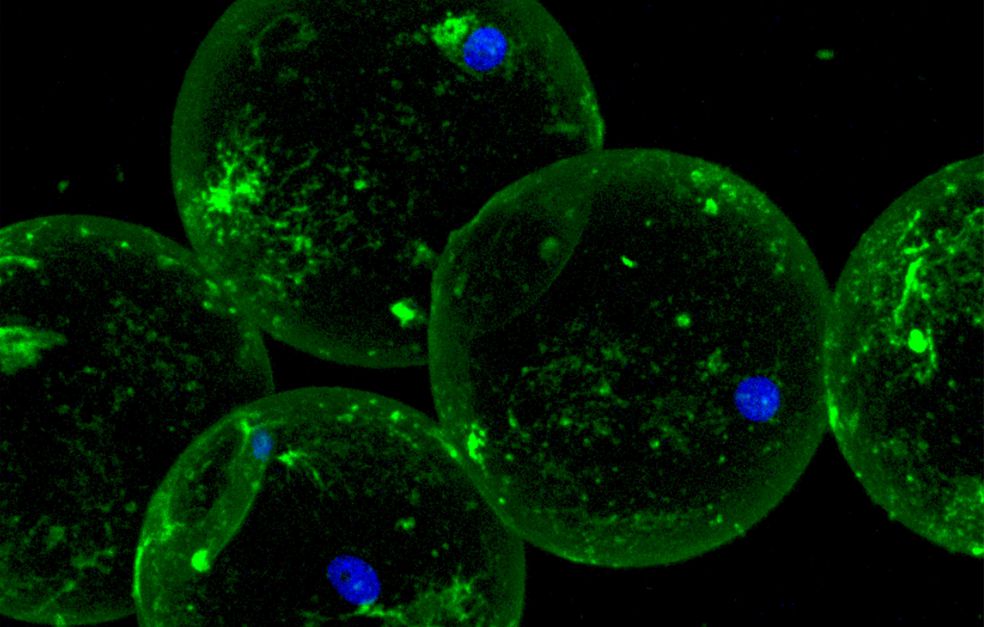

Cells outside the body like those inside

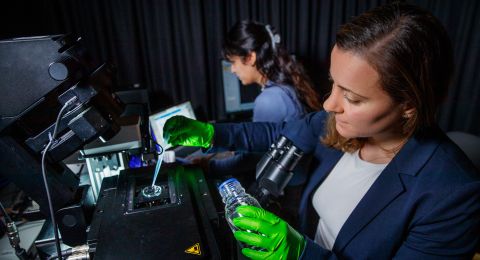

The subjects in the study start by providing a small tissue sample. A local anesthetic is given and a needle is inserted close to the navel to extract two or three grams of fatty tissue. The researchers clean the tissue and dissolve it using an enzyme, so the fat cells separate from each other. They can then be stimulated with various substances, like stress hormones, which stimulate fat decomposition, or insulin, which increases fat storage.

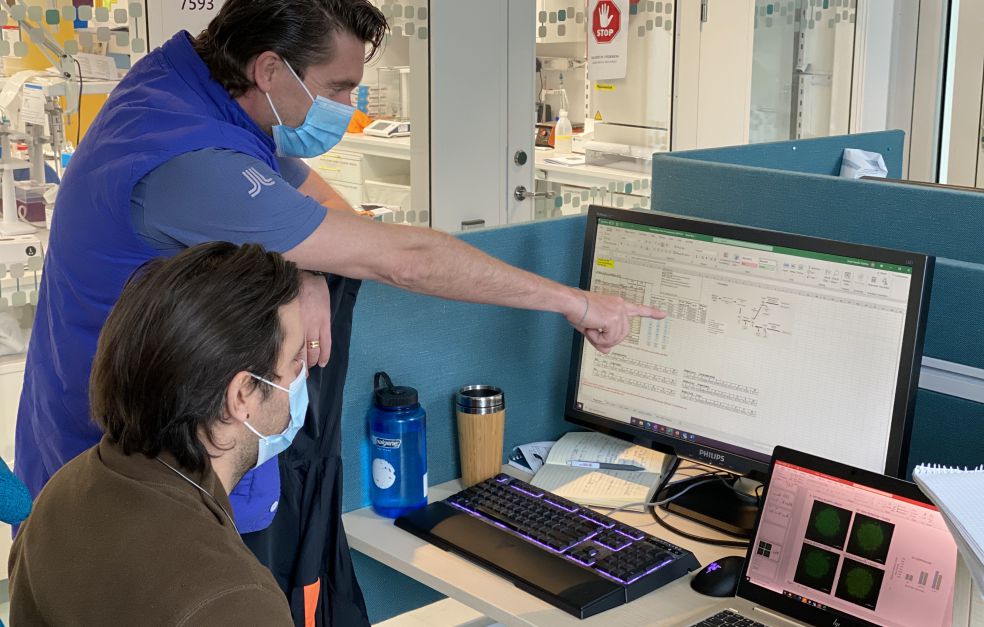

“We know that the cells’ reaction to these substances very closely mirrors how they work in the body, and that their ability to metabolize fat is critical. We’re also studying proteins and decomposition products in the cells, and are examining our subjects very thoroughly – how much adipose tissue they have, where it is, how sensitive to insulin they are. The aim is to see how the traits of the fat cells can be linked to health.”

Among other things, Rydén has seen signs that cell metabolism is compromised in obesity so that it starts to produce inflammatory substances. These can trigger the body’s immune system, potentially resulting in disease. He has also begun to differentiate between different types of fat cell, which may have different roles. But first and foremost he is studying the breakdown of fat in the cells, a process known as lipolysis, which is impaired in many diseases related to overweight.

Tape measure shows who needs help

To date Rydén has been able to show that impaired lipolysis is linked to high long-term weight gain. But lipolysis is tricky to measure, and so he is also making studies with the aim of assessing lipolysis using methods that work in normal health care.

“Using a combination of simple yardsticks such as insulin production and waist-hip ratio, it’s fairly easy to work out whether someone has high or low lipolysis. This might be a way to identify people who should make a special effort to prevent problems arising.”

Scientists have long sought genetic explanations for obesity and related diseases such as diabetes. Rydén no longer thinks this is the right way to go.

“The specific gene sequence we have explains only a couple of percent of an overweight person’s elevated risk of disease. I think that metabolism of fat, and the combination of genes that are active in adipose tissue, are much more important factors in identifying people at risk of complications.”

Curiosity and sure instinct

As a child, Rydén was something of a nerd, a collector who had several hundred candles under his bed. Then it was model cars, followed by stereo systems. He has always been interested in the details of how things work. His first research project was for his PhD thesis in neurobiology, focusing on a small group of substances in the nervous system, which he studied in the laboratory. He enjoyed the work, but afterwards felt that he wanted to do more patient-related research. A colleague asked him if he would like to specialize in adipose tissue. He said no at first – he didn’t think he would enjoy endocrinology, which includes the study of hormones and diabetes. But he was wrong.

“I love it – it’s a huge intellectual challenge, requiring careful thought and discussion. It still involves a large element of intuition, since we don’t yet have many tried and tested treatments. I was soon hooked. When I started, I was also able to contribute lab experience that not many of my colleagues had. I felt useful.”

Nowadays he spends 70 percent of his time on research, and the remainder at the clinic. He has a normal outpatient clinic and does his rounds just like his fellow doctors.

“My day-to-day work is important so I can keep abreast of developments. It gives me confidence. Working as a doctor helps me to know the questions I should be asking in my research, and research helps me to understand pathological mechanisms in my role as a doctor.”

Text Lisa Kirsebom

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Niklas Mejhert, Mikael Rdén, Christina V. Jones