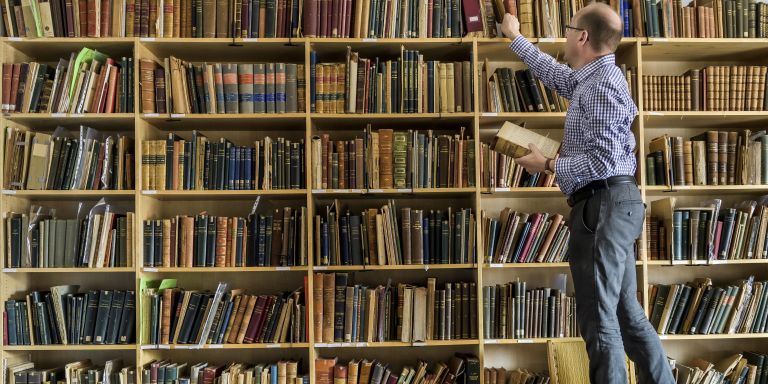

In Canada there are monuments to Ukrainian history rooted in nationalism and anti-Semitism. When historian Per Anders Rudling came across the phenomenon, it awakened his curiosity. He is now researching the Ukrainian diaspora in Canada, and how their memory culture and historical accounts have political consequences in modern-day Eastern Europe.

Per Anders Rudling

Associate Professor of History

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, Prolongation grant 2024

Institution:

Lund University

Research field:

Culture of history, nationalism and ideological use of history in Kresy Wschodnie, the border zone that is now western Belarus, western Ukraine and Lithuania

Having researched abroad for many years, Rudling has returned to Sweden. He is building on the long-established and renowned Eastern European research at Lund University carried out by researchers such as Kristian Gerner and Klas-Göran Karlsson.

“Sadly, interest in Eastern European research has declined in recent years, but thanks to the Wallenberg Academy Fellow scheme, we can now revitalize the field with a new generation of historians.”

Rudling first became acquainted with Eastern Europe when he was studying Russian at high school. They were turbulent times, with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union. He went on to study Slavic languages at Uppsala University, where he developed a growing interest in countries that had become marginalized.

“In those days hardly anyone wanted to write about Belarus, Ukraine or Moldavia. Anywhere beyond the Baltic States was seen as a black hole.”

Rudling received a scholarship to study in St. Petersburg. This both whetted his appetite and furthered his academic career, during which he has lived in Russia, the U.S., Canada, Germany and Singapore. His research has included Polish-Ukrainian-Jewish relations.

“Being chosen as a Wallenberg Academy Fellow is the greatest acknowledgement I’ve received as an academic researcher. As a historian specializing in Eastern Europe and as someone in the humanities, I see the grant as a unique opportunity to build a research team. It has also given me the opportunity to move back to Sweden, which has fundamentally changed my life.”

Large Ukrainian diaspora

During his time in Canada Rudling became interested in the Ukrainian diaspora, one of the largest minorities in the country, numbering about 1.3 million people. Some of them migrated as far back before as the First World War from the Habsburg Empire; others did so between the wars. A third category comprises refugees after World War II and their relatives.

“Many in the ‘third wave’ were radical nationalists. A number of them had served under the Germans on the eastern front and were strongly anti-communist and authoritarian.”

Once in exile, the Ukrainians began to create their own memory culture. Over time the most politically articulate of them have taken over large parts of the institutional life of the diaspora.

“They started cultural societies, put up candidates in political elections, and formulated an account of Ukrainian history with a radical agenda.”

History has been revised and certain accounts highlighted; others are suppressed. Nowadays the collective memory emphasizes the sacrifices made by Ukrainians during the disastrous years 1932–1933 under Stalin’s rule. But less mention is made of controversial links to Nazism and the Holocaust.

Ukrainian nationalists such as Stepan Bandera and Roman Shukhevych are hailed as freedom fighters, even though they led totalitarian organizations, and were responsible for bloody pogroms. The Polish minority in western Ukraine was subjected to ethnic cleansing between 1943 and 1944; about 100,000 people were killed. Waffen-SS Galizien was a Ukrainian division in the service of Germany, some members of which have been linked to brutal attacks on Polish and Jewish civilians.

“But commemoration of the Holocaust remains, to some extent, a taboo. It has become a non-memory.”

Monument with Nazi associations

Rudling was surprised to come across a monument to Ukrainian nationalists and the Waffen-SS Galizien division on the other side of the Atlantic in Canada.

“One of the first things the Ukrainian exiles did after the introduction of official multiculturalism in Canada was to build a large monument to Shukhevych, who fought against the Soviet Union. But between 1939 and 1943 he also fought in a German uniform, and stood under Himmler’s direct command on the eastern front.”

Rudling’s curiosity was aroused even more when he understood that this nationalist agenda had been paid for with state cultural funding.

“Canada, a liberal country, was the first country in the world to introduce normative multiculturalism in 1971. This means that nationalistic associations and groups can receive funding.”

Since Ukraine gained independence in 1991, exile groups have begun to exercise political influence in their former homeland. The ideological use of history shaped in the diaspora is now being re-exported to Ukraine. A statue of Bandera was unveiled in the city of Lviv as recently as 2007.

“The minority in Canada produced a gallery of ready-to-use national heroes, which now forms the basis for a new national memory in Ukraine.”

Creating new conflicts

Germany is perhaps the country that has made the greatest effort to come to terms with its grim 20th-century history. But the concept, referred to by Germans as Aufarbeitung, is not applied in a number of post-socialist countries. New political conflicts arise as a result. Ukraine’s rehabilitation of highly controversial historical figures of the recent past has caused widespread dismay and anger, not least in neighboring Poland.

“Whereas Ukraine has banned any expression of disrespect for its national hero Bandera, Poland has made it a criminal offense to glorify him. Here we can see two neighboring states, both strongly anti-communist, but with mutually exclusive and incompatible memory cultures in regards to key moments in their modern history.”

Rudling is researching into different aspects of long-distance nationalism, which is a growing phenomenon. He says it is a paradox that liberal policies have given a boost to nationalistic forces. Ukraine is just one example. In a world with large migration flows, similar processes can be seen in many places.

“Among other things, we have seen how Recep Erdogan, the president of Turkey, has directed campaign messages to Turks in the Netherlands and Germany. And Sweden, too, has what might be termed ‘professional nationalists’, who are heavily involved in the politics of their home countries, with a desire to control how history is written.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Kennet Ruona