Project Grant 2022

Sex matters in autoimmune disease

Principal investigator:

Professor Marie Wahren-Herlenius, Karolinska Institutet

Co-investigators:

Karolinska Institutet

Olle Kämpe

Björn Reinius

Uppsala University

Nils Landegren

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Grant in SEK:

SEK 39.1 million over five years

In autoimmune diseases the immune system attacks the body’s own tissues. Some of them, particularly rheumatic diseases, affect women much more often than they do men. Sjögren’s syndrome is an extreme example: nine out of ten patients are women.

Researchers at Karolinska Institutet and Uppsala University are seeking an explanation, and are also trying to understand the general factors distinguishing the male immune system from its female counterpart.

“Three out of four people with rheumatoid arthritis are women, as are two out of three with multiple sclerosis. There are examples to the contrary, where almost all sufferers are men. But there has been very little research into differences between the male and female immune systems,” says Marie Wahren-Herlenius.

She is Professor of Experimental Rheumatology at Karolinska Institutet, and is heading the project, which is being funded by Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

A number of DNA variations are associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. All of them are also common in healthy people, but the more variations an individual has, the greater the risk of developing Sjögren’s syndrome – if the carrier is a woman. The researchers are studying both fundamental differences between male and female immune systems, and differences specific to this particular disease. They hope their findings will provide a basis for better therapies.

Differentiated genes and hormones in mice

One way of studying the immune system involves using genetically modified mice, bred for research purposes. Normally, mice – like humans – have X and Y chromosomes if they are male, and two X chromosomes if they are female. But these mice have been modified so XX mice can be bred with male sex organs and XY mice with female sex organs. This enables the researchers to distinguish between sexual differences driven by chromosome genetics from hormonal differences, primarily occurring in testicles and ovaries.

“These mice have been available for research for a while now, but no one has characterized their immune system,” says Wahren-Herlenius.

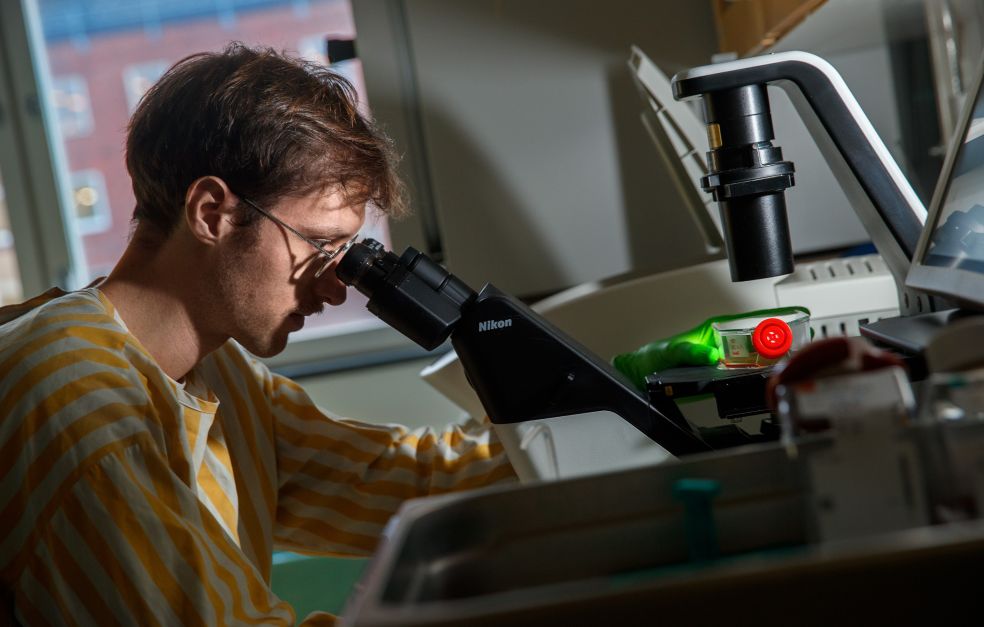

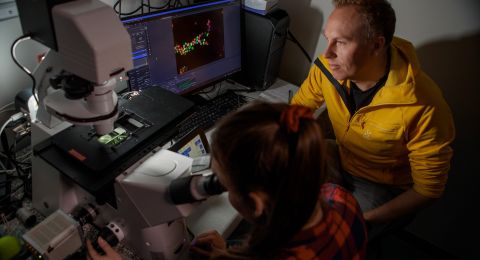

The researchers are using single-cell genomics to study genetic activity in individual immune cells in mice. They are looking for patterns related to the hormone and chromosome variants.

New insights from transpersons and chromosome deviations

The next step will be similar studies on humans. Different groups of subjects will enable the researchers to study how either hormones or chromosome combination impact the immune system. One such group comprises transpersons – people who consider themselves to have been born the wrong sex. They undergo hormone treatment to acquire the right sex characteristics. Their chromosomes remain the same but their hormonal environment is changed, which makes it possible to study how sex hormones impact the immune system.

The opposite applies to another group of study subjects. In this case the hormones are constant, either typical of women or of men, but gene and chromosome composition vary between the individual’s cells. These are people born with chromosome abnormalities, where, for example, certain cells may have only one X chromosome, and others one X and one Y chromosome.

“The fact that women are more prone to develop autoimmune diseases may be the price we pay for an immune system that seems to respond more effectively to infections. We saw this recently during the Covid pandemic, when men ran a greater risk of becoming seriously ill,” Wahren-Herlenius points out.

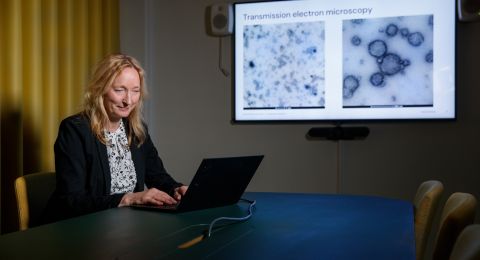

The researchers will also be studying Sjögren’s syndrome specifically, to gain insights into the importance of risk variants in DNA. These might be linked to signal pathways in the body’s cells that could be blocked by a new therapy.

“I believe that by studying hormones and genetics separately we’ll be able to show that Sjögren’s syndrome is due to interaction between them.”

Finding the underlying mechanism

The researchers have different fields of expertise, including regulation of genes in X chromosomes, sequencing technologies and single-cell analyses, studies of human hormones and sex chromosomes, as well as rheumatology and Sjögren’s syndrome.

“This team represents a new spectrum of combined skills, which is really exciting. Everyone is making contributions that are completely new to the rest of us.”

One challenge is to recruit skilled bioinformaticians to the team to analyze the huge quantities of data produced. According to Wahren-Herlenius, expertise of this kind is in short supply in Sweden.

Another potential challenge is if the genetic factors identified prove to have a fairly limited impact on the disease. In that case the researchers will need a large number of subjects to demonstrate the link, which will entail collaboration with researchers in other countries.

“And if we find a genetic variant that obviously has various impacts on the immune system in women as compared with men, the question of course is why this is so. As far as I know, no such mechanisms have yet been described. Perhaps we won’t be able to find them either. But I hope we can. I hope that in a few years’ time we will have identified a number of factors, as well as how they control the diseases.”

Text Lisa Kirsebom

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström