Demographic inequality – social differences in health, longevity and family formation – is nothing new. But how have such differences shifted throughout history, and what drives them? This is what Wallenberg Scholar Martin Dribe is studying at Lund University.

Martin Dribe

Professor of Economic History

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Lund University

Research field:

Long-term trends in demographic inequalities and factors that contribute to inequality in people’s lives

Population illness and health, fertility, mortality, family formation and migration are some of the factors included in the concept of demography. Dribe, professor of economic history at Lund University, is currently studying demographic inequality from the early 1800s to the present day.

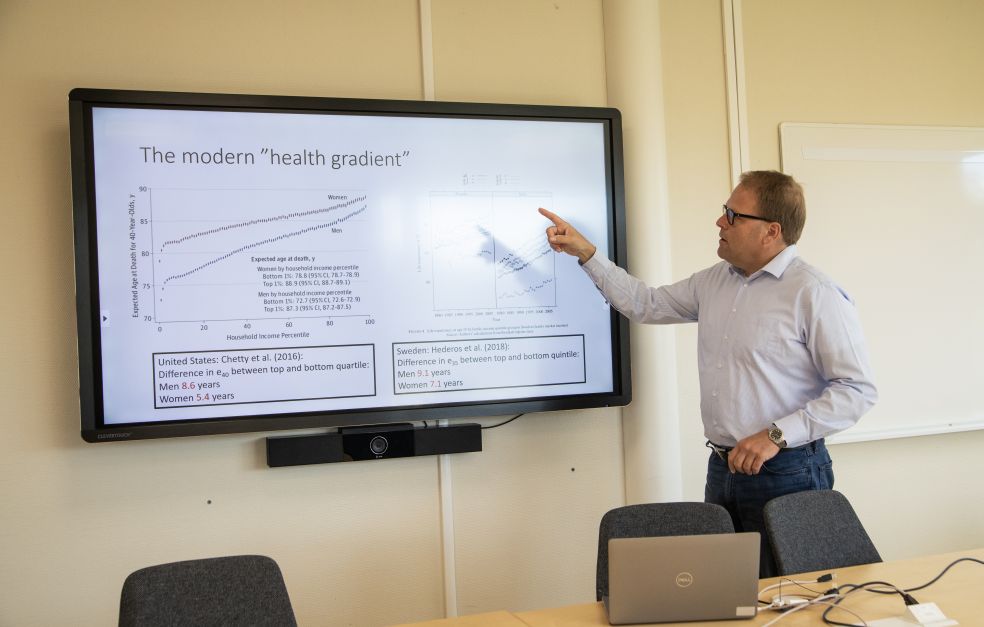

Among other things, he has conducted a historical analysis of socioeconomic differences in mortality among adults. Today, lower socioeconomic status is linked to poorer health and higher mortality, but with demographic data from the late 1800s and early 1900s, Dribe and his colleagues were able to show that the picture was entirely different back then.

“The socioeconomic gradient in mortality among adults is a fairly modern phenomenon. After 1970, we get a distinct gradient in mortality – not only is there a difference between rich and poor, but also those with only slightly higher income or status have better health and live longer. This is how it looks in all developed countries today.”

Social differences in health and mortality have widened since 1970 in countries with relatively marked economic equality such as Sweden, and in more unequal countries such as the United States.

Dribe is not the first to note the lack of this gradient in earlier years, but he has backed up these findings with significantly more data.

“Among those born in the mid- or late 1800s, it was in fact men that had the highest socioeconomic status who had the shortest life expectancy.”

It is not really known why this was the case. It is difficult to ask people who died a hundred years ago how they lived their lives, notes Dribe. But there are some statistics from the time on alcohol and tobacco habits, and surveys on what people consumed. Possibly the shorter lives of the rich men were due to sedentary work, alcohol, smoking (which was more common in the upper classes at the time) and diet increased the incidence of cardiovascular disease. The fact that they had better access to healthcare was probably less important, because there was not much healthcare on offer.

“With the development of modern healthcare and the emergence of the welfare state, paradoxically you see increased socioeconomic differences in health.”

Linked databases make it possible to research generations

Dribe’s research is based on large amounts of data from sources such as church records, population registers and historical censuses. Old address data make it possible to ‘geocode’ people on maps.

Data from the 1960s onwards is available from Statistics Sweden and the researchers in Lund work with the Swedish National Archives and colleagues at other universities. The SwedPop national research infrastructure links the five most important historical databases on Sweden’s population so people can be followed throughout their lives and down generations.

“SwedPop data has been harmonized and coded so it’s comparable and accessible to anyone who wants to research it,” says Dribe.

The ability to follow the entire arc of people’s lives is worth its weight in gold for a historical demographer, and thanks to modern technology and digitization, links between historical and modern data are becoming increasingly common. And Sweden is an exceptionally good place to do this.

“Many countries lack comprehensive population registers for recent decades and not all have legislation like ours, which permits research on personal data from such registers.”

Neighborhoods more significant than parents’ profession

Dribe and his colleagues have used a method that involves unusually precise geocoding. Rather than determining where people are brought up purely based on city districts, each individual is allocated a point on a map that can be linked to a number of their closest neighbors, so that you can easily vary the size of a neighborhood.

Using such detailed analysis, the researchers have been able to show that it is beneficial to grow up in areas with large numbers of adults who work in white-collar professions. As adults, children from such environments tend to enjoy better health and lower mortality and stay in education for longer. This also applied if their own parents were less educated or were civil servants.

“Perhaps this is related to peer effects, good role models... There are lots of theories about this.”

Dribe himself grew up in Kristianstad, southern Sweden, with parents who did not have a higher education. His own early image of university was that you went there to become a teacher, lawyer, doctor or an engineer.

“I had no idea there were people who read subjects just for fun. Personally, I’d planned to study economics but realized that I probably didn’t really want to work in a bank. So, I started studying political science simply because it interested me.”

He quickly became fascinated by population history and already during his student years he authored essays on the subject. Today, he hopes that his research will increase understanding of inequalities in society, how they arise and how we can influence them.

"The existence of social differences is nothing new, but we’ve been able to show that some of them are very recent phenomena. These aren’t historical constants that can’t be changed, but a product of the society we have. That’s a key insight.”

Text Lisa Kirsebom

Translation Nick Chipperfield

Photo Åsa Wallin