Many children in Sweden survive even if they are born as early as week 22 of pregnancy (instead of the normal 38-42 weeks).

“Some even survive in week 21. Sweden and Japan are unique in this respect. Most countries do not save children born earlier than week 25,” Hellström explains.

Babies born so prematurely are far from fully developed, which means they must receive highly advanced medical care. They run a high risk of suffering from a number of diseases, both at the time of birth and later in life.

“One organ system often affected is the eye and visual system. Eyesight is closely related to the brain, so if the eyes are affected, then the brain often will be too,” says Hellström, who is a pediatric ophthalmologist.

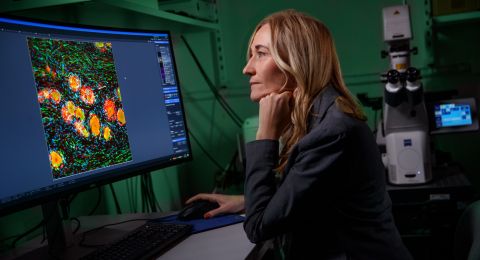

For the past 25 years she has worked both as a doctor and a researcher to reduce the risk of children becoming sick or poorly developed. An abiding theme during this time has been that of what is in children’s blood. Among other things, her research team has mapped growth factors and fatty acids in the blood of infants, and studied ways of reducing the quantities of blood taken from them.

Screening fewer children

The focus has been on an eye disorder called retinopathy of prematurity (ROP). The disease, which is caused by abnormal blood vessel growth in the retina, results in impaired vision and sometimes blindness. It is not uncommon among premature infants. All children born before the 30th week of gestation are screened for ROP. This may be done from 3–4 times up to 20 times during the neonatal period. Only about six percent of the 1,000 or so children screened every year need treatment. Treatment is either by focal laser therapy or use of special antibodies.

Hellström and her colleagues would like to see fewer infants screened because the examinations are unpleasant and painful for them. Instead, they want to identify children in the risk zone and focus their efforts on them.

The team has previously mapped different levels of growth factors in blood, and discovered that the IGF-1 growth factor was very low in children who developed ROP. These results form the basis for work in progress at one drug company. The team is conducting another study in which it is examining fatty acids in children’s blood.

“The mother passes on DHA, which is an omega-3 fatty acid, to the child towards the end of the normal pregnancy. This means that preemies have very low omega-3 levels. Another fatty acid passed on by the mother to her baby is omega-6, which is an important building block during the fetal stage. The balance between different fatty acids is a delicate and complex one, and not always easy to restore later on,” Hellström points out.

But in a recently concluded study, funded by the Swedish Research Council and the Foundation, newborn premature infants received a daily dose of a solution containing both these fatty acids until week 40 (normal term). The results look very promising.

Adult blood

A third line of inquiry concerns the quantities of blood taken from prematurely born infants.

“Nearly 60 percent of their blood is replaced as samples are taken for clinical analyses and research. Children born after 22 weeks of gestation have, over time, their entire volume of blood replaced. The infants’ fetal blood is replaced with blood from adults. Hellström believes this has a negative impact on them.

“Fetal blood is constituted to enable the infant to develop in the best way. It contains more stem cells, and their hemoglobin in the blood cells, which transport oxygen, is composed quite differently. If we could reduce the quantity of blood taken from these children by 50 percent, much would be gained. Every drop counts.

In the future, the idea is to reduce the amount of blood taken and add red blood cells from fetal umbilical cord blood, working with the Umbilical Cord Blood Bank in Gothenburg.

“We are convinced that their health would improve, and that nerve tissue and vessels would continue to develop, since fetal blood has the ability to transport oxygen farther out to the organs. The children who develop serious ROP and a lung disease called BPD are also those with the lowest levels of fetal blood.

“We would never have been able to do everything we’ve done without ‘no-strings’ funding from the Foundation. Most funding sources demand preliminary results before they approve a grant. The Foundation commits to projects it believes in even at an early stage.”

Most blood discarded

She considers that one success factor has been interdisciplinary collaboration, and the fact that her research team possesses expertise in so many fields, including biomedical analysis. She has understood from the specialists in that field that the majority of all blood taken from preemies is thrown away

“We have discovered that surplus blood is taken merely to suit the requirements of the analytical equipment, and that most of it is then discarded. This has to stop.”

To reduce the quantity of blood taken from infants, a biobank has been started to save surplus blood removed as samples, provided parents’ consent. Researchers wishing to use blood from infants born prematurely can now turn to the biobank instead.

“The biobank is globally unique. We already have 1,200 samples. The response from parents has been fantastic.”

Digital solutions

Since the inception of the biobank a great deal of time and effort has been spent on digital solutions to maintain contact with parents, and also to ensure the biobank is available and secure for research purposes. Machine learning has been used to produce algorithms to predict which children run the highest risk of developing ROP. They have also initiated solutions enabling data to be transferred at the push of a button from medical records to the quality register.

“Quality registers are essential to develop and continuously optimize medical care. But we know that one in twenty values is wrong when they are put in by hand, and it is also time consuming. We hope that we now have a simple, digital solution that can be launched in the Gothenburg region early next year.”

In addition to all the above and more, Hellström is engaged in a long-term project monitoring the progress of preemies.

“Those of us who work with these children also have a responsibility to see what happens to them. Extensive resources are expended on them to start with, but later on the children and their parents are pretty much on their own – unfortunately.

Text Carina Dahlberg

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Ann-Sofie Petersson, portrait Mikael Sjöberg, test tubes Johan Wingborg