Camilla Svensson is seeking new explanations for pain and chronic discomfort, not only in the sensory nerves, but also in their immediate surroundings – among antibodies, satellite glial cells and macrophages.

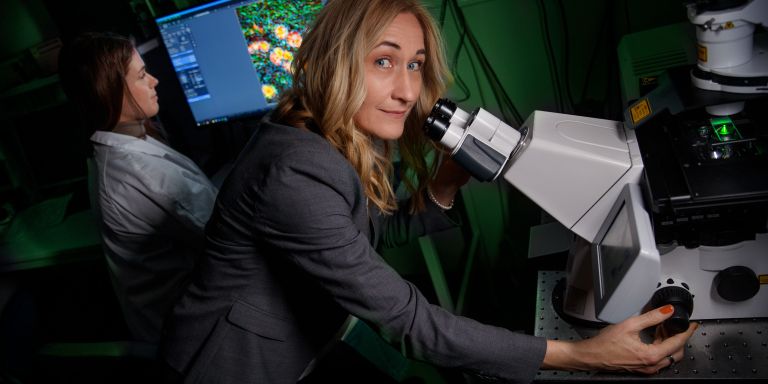

Camilla Svensson

Professor of Cellular and Molecular Pain Research

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Research field:

Cellular and molecular pain research

Svensson, who is a Wallenberg Scholar and professor of cellular and molecular pain physiology at Karolinska Institutet (KI), is leading a team of some 20 researchers studying the causes of pain conditions linked to rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia.

In the past, the widespread, long-lasting pain that often affects women was often met with skepticism among healthcare professionals. But Svensson and her research team have made substantial progress in the search for biological explanations, and they hope that further research can pave the way for new more effective treatments.

“Knowing how important this issue is to both patients and the healthcare system gives me the energy and motivation to keep pushing forward,” she says.

To understand how pain develops in conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia, the research team is investigating cellular changes in the blood, muscles, skin and dorsal root ganglia in humans and, when needed, in mice.

The dorsal root ganglia – clusters of sensory nerve cells located near the spine – contain the cell bodies of sensory neurons that detect sensations like pain, touch and temperature. These neurons transmit information through their axons to the spinal cord, where the signals are processed and sent on to the brain for interpretation.

What changes?

“We’re currently focusing on what happens in a nociceptor (pain nerve) in the skin, muscles or joints in connection with fibromyalgia and arthritis. We’re trying to understand what changes in the nociceptor’s environment make it overly sensitive, causing it to transmit more impulses than normal – or even pain signals in response to stimuli that shouldn’t hurt at all,” she says.

The research team has previously studied antibodies from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and how these can affect nociceptors. More recently, they have now isolated antibodies from patients with fibromyalgia and injected them into mice – an experiment that led to widespread sensitivity and skin changes similar to those observed in fibromyalgia patients. This is a groundbreaking finding.

Surrounding the cell bodies of neurons in the dorsal root ganglia are satellite glial cells, which form a tightly connected network. These cells can sense and respond to changes in their environment, and in doing so, influence the activity of nearby nociceptors.

In fibromyalgia, certain antibodies may bind to these satellite glial cells, triggering increased activation. This has been observed after injection of antibodies from fibromyalgia patients into mice and in tissues from humans.

There may be an immunological change that has not previously been understood.

Establishing model systems

“About 40 percent of the fibromyalgia patients we’ve studied have antibodies in their blood that bind to satellite glial cells, so this response is not present in everyone with the condition. But what is very interesting is that the strength of this antibody binding to satellite glial cells may be linked to how much pain the individual experiences,” Svensson explains.

The KI researchers are now establishing model systems in which they use human satellite glial cells to explore how the antibodies affect cell function. They have also obtained dorsal root ganglia from organ donors who had been diagnosed with fibromyalgia. This will allow them to map changes in neurons, satellite glial cells, and macrophages – a type of immune cell.

In addition, they will measure whether individuals with fibromyalgia have higher-than-normal levels of antibodies in their dorsal root ganglia, since early findings suggest this may be the case.

“We know we’re dealing with IgG antibodies, but we still don’t know which specific subclass of IgG is involved. The answers we obtain will be key to understanding how the immune system is affected,” she explains.

Changes in nociceptors

In a complementary study, the team is comparing skin biopsies from fibromyalgia patients with those from healthy individuals.

Svensson elaborates:

“Previous research has shown that the nociceptors in the skin are altered in 30–40 percent of fibromyalgia patients. Our data also reveal unexpected changes in other skin cells, suggesting an immune imbalance that hasn’t been recognized before. We want to understand exactly what kind of immune shift is taking place. What we’re observing doesn’t match other known diseases and may point to changes that are unique to fibromyalgia.”

Several exciting therapy-related studies are now under way.

“We’ve been able to follow a Belgian company testing a drug in a small study involving fibromyalgia patients”, she says. “The drug works by increasing the breakdown of antibodies in the body. The results are expected to be published this fall.”

The team is also preparing a collaborative study with the Rheumatology Center in Stockholm and several other clinics in Sweden to investigate whether other immunomodulatory treatments could relieve pain and fatigue in fibromyalgia patients.

Text Monica Kleja

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström