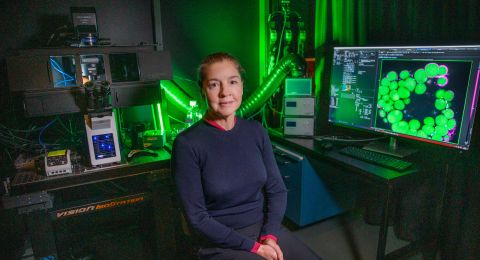

In a few years’ time there may be a completely new kind of stem cell treatment for age-related macular degeneration. The therapy is based on Fredrik Lanner’s research into stem cells and early development in human embryos. Using refined methods of studying both donated and synthetic embryos, he aims to develop more cell therapies, and to understand the reasons for infertility.

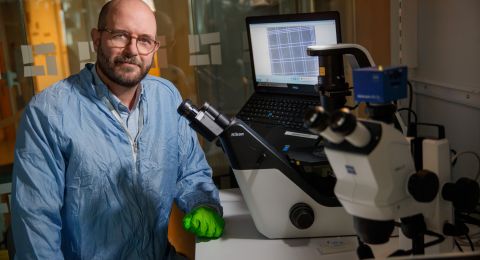

Fredrik Lanner

PhD Developmental Biology

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, prolongation grant 2021

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Research field:

Human embryonic stem cells – modeling of early embryonic development, and development of stem cell therapies

“My research centers on human embryonic stem cells (ESCs), which form during the first few days after an egg has been fertilized. Human embryo development and mechanisms are different than those in mouse embryos, for instance. So if we want to understand human developmental biology, we need to study the human embryo,” Lanner explains.

His laboratory is at the Novum research park in Flemingsberg. The research team is studying donated embryos from the IVF Clinic at Karolinska University Hospital, which is right next door.

"These are embryos that are not used in treatments for infertility, and that would otherwise be destroyed. Instead they can be donated for research,” says Lanner.

The research is driven by a desire to understand the fundamental molecular mechanisms in the early stage of life, as well as to learn more about the causes of infertility.

“The biology itself is absolutely fascinating. But learning more about the causes of infertility is also of enormous interest, and a topic dear to my heart. Although we still have quite a long way to go, I believe the fundamental scientific platform on implantation biology we’re building will ultimately help involuntarily childless couples.”

Lanner’s second line of research involves using embryonic stem cells to develop new therapies for macular degeneration, an eye disease caused by age-related changes in the macula. The work is being carried out in collaboration with eye surgeon Professor Anders Kvanta at St. Erik Eye Hospital in Stockholm and Novo Nordisk, a pharmaceutical company. They aim to begin a clinical study in 2023.

“We’re really pleased with the progress we’ve made together. We hope that if we can transplant these cells in the patient at an early stage, we’ll be able to halt the loss of vision. It’s a completely new kind of cell therapy – one produced in Sweden. So we’re doing everything for the first time, which is both enjoyable and challenging.”

Embryo models

Earlier, with funding from Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, Lanner has studied embryonic development during the first week after fertilization. This is the period during which the embryo, known as a blastocyst at this early stage, attaches to the wall of the womb, and implantation occurs. This is also the period during which the embryo is cultured in IVF.

“The Fellow scheme enables me to focus long term on the research I consider to be most promising. I can continue with embryo research, as well as development of cell therapies from human embryonic stem cells.”

“From the point at which the blastocyst attaches to the wall of the womb until the woman becomes pregnant numerous interesting processes occur – processes that we know very little about, since there are so hard to study. So we are now extending our embryo studies to the second week by implanting donated embryos artificially in the lab and culturing them for an additional week.”

A major development in the field over the past few years is that it is now possible to create synthetic embryos or embryo models from embryonic stem cells.

“This is a new tool for understanding and modeling early embryonic development. We can create something resembling a blastocyst in the lab, and study how it is built up. That makes it even easier for us to examine the second week of embryonic development. We can use the synthetic embryos instead of being dependent on donated ones. We’re delighted about this.”

Lanner and his research team produced the first gene map of the first week of embryonic development. This is now the basis of their further research. They are also taking steps to verify and fine-tune the new methods of creating synthetic embryos.

“We’ve been able to use our gene map to help determine which genes the different cell types express. In collaboration with several researcher partners, we’ve also started to extend the gene map to day 14.”

Replacing photoreceptors

The goal has always been to carry out a clinical study in Sweden in collaboration with St. Erik Eye Hospital on stem cell therapy for macular degeneration. If everything goes according to plan, it will start in early 2023. Partnership with Novo Nordisk has given impetus to the initiative.

“It’s a big plus to have the support of such a large drug company. But for me this is new ground – both producing a completely new drug, and collaborating with industry. But it’s gone very smoothly and been a real pleasure.”

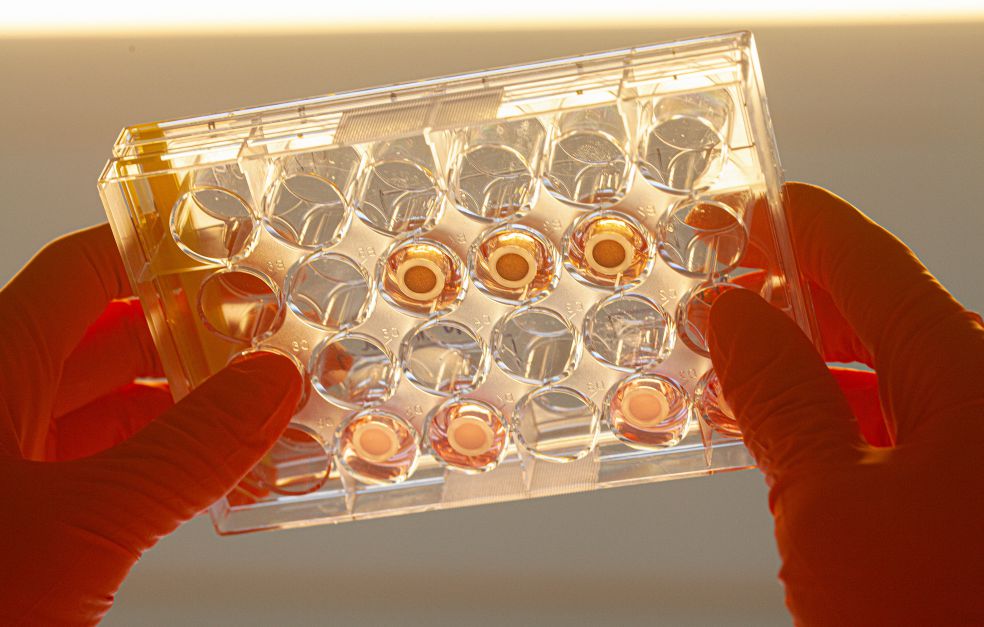

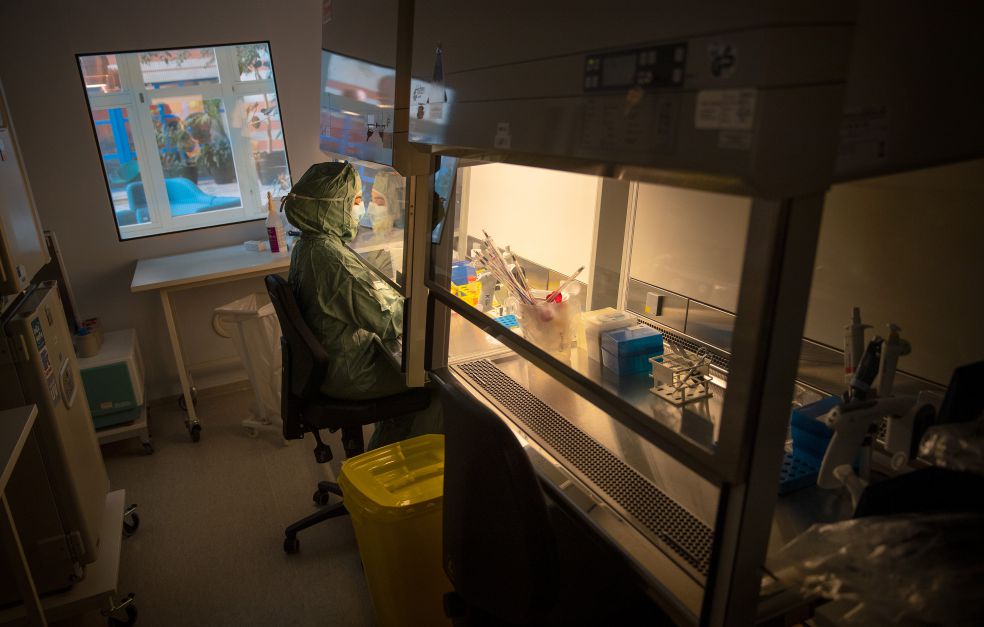

The retinal pigment epithelial cells to be transplanted are cultured from embryonic stem cells under rigorously controlled conditions at Karolinska University Hospital’s ultraclean cell therapy facility.

As part of the Wallenberg Academy Fellow project, he wants to take cell production a step farther, to recreate sight in the macula.

“So far we’ve produced the support cells needed to preserve the remaining vision and photoreceptors – rods and cones – in the eye. Now I want to try to produce new photoreceptor cells. Hopefully, in a few years’ time we’ll also be in a position to carry out clinical studies on replacing rods and cones.”

Text Susanne Rosén

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström