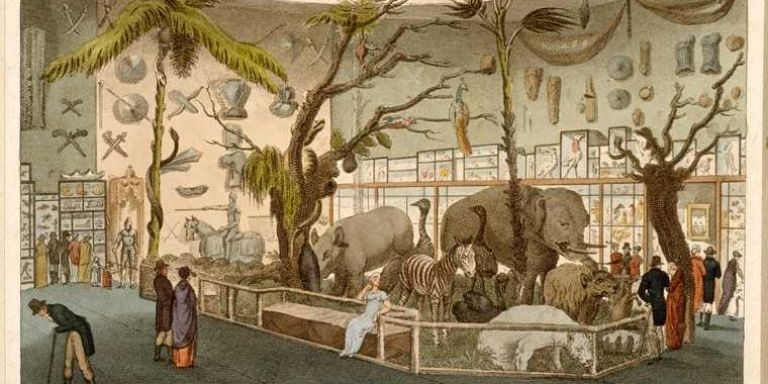

Citizen science, where members of the public help researchers in various ways, is not a new phenomenon. Natural history evolved in the 18th century as the fruit of collaboration between universities, museums and laymen. Carl Linnaeus – was a forerunner, and historian of science Linda Andersson Burnett is now studying how his ideas influenced developments far beyond Sweden’s borders.

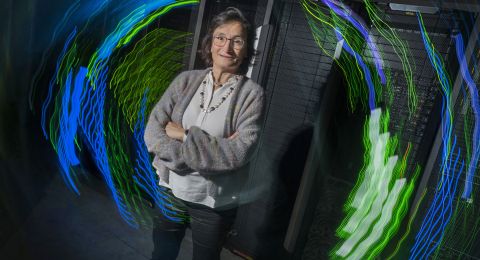

Linda Andersson Burnett

PhD, History

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2019

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

History of science, including Linnaean natural history, transnational history, colonial collecting and citizen science

In the mid-18th century, Linnaeus wrote instructions how natural historians should collect and record the natural world. His ideas were embraced by his students, known as the Apostles of Linnaeus”, but were disseminated internationally, lending impetus to the development of science resulting from interaction between amateurs, academics and museums.

Earlier research has focused on the espousal of Linnaeus’ teachings by professors and prominent scientists, but Andersson Burnett is now exploring how Linnaeus’s legacy gained a foothold among the general public.

“The focus has often been on Linnaeus’ instructions to his apostles, rather than the impact they had on society in general.”

Lived in Scotland

The idea for the new project was hatched in Scotland, where Andersson Burnett lived and studied for 14 years.

“I have researched the methods of teaching Linnaean natural history at Scottish universities during the Enlightenment in the 18th century. Surprisingly, we found that great importance was attached to Linnaeus’ expedition to Sápmi and his ideas about how to travel and gather knowledge and specimens.”

Linnaeus’ accounts of journeys in Sweden attracted interest in the British Empire, and inspired people of the day to explore their own local areas.

“Great Britain was at the forefront when it came to spreading Linnaeus’ teachings outside Sweden. Linnaeus’ own collection was even purchased from his family, and the Linnean Society of London was founded in 1788.”

Interest in natural history took root in society, and a wide variety of people became involved in contributing to the research, including merchants, landowners, military officers, sailors, priests, council officials, missionaries. Even Indigenous people and enslaved people joined the networks that took shape.

“Fundamental questions I would like answers to are how researchers and lay citizens collaborated, and how interaction between the public and university museums evolved during the period 1750–1850.”

“The Wallenberg Academy Fellow grant is the best thing that’s happened to me as a researcher. It gives me both resources and time to conduct long-term research based on more challenging source material. It also enables me to build up a team, which is unusual in the humanities.”

Varied source material

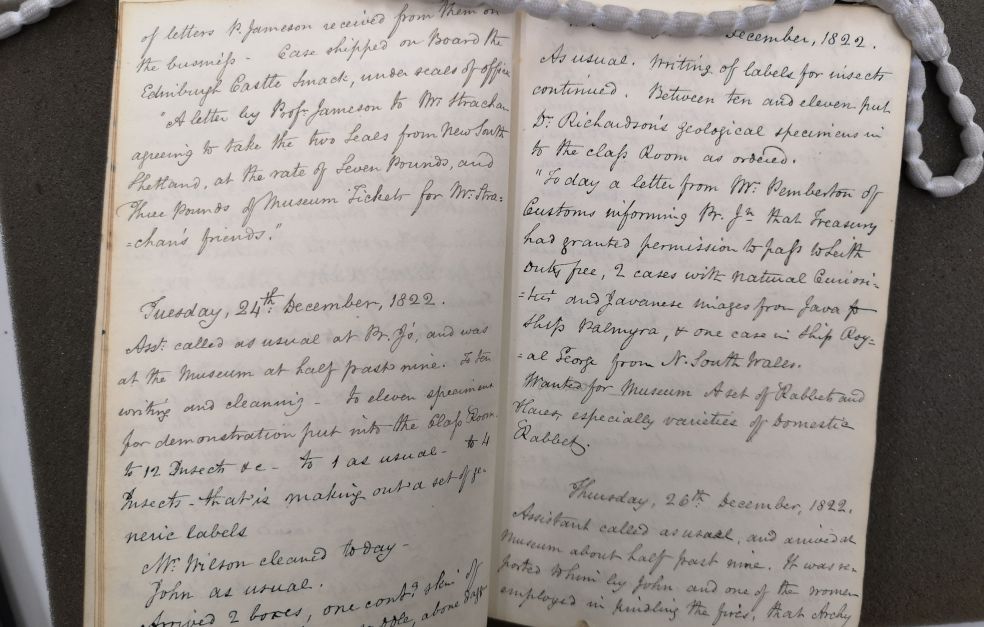

Andersson Burnett finds most of her source material at two university museums, in Aberdeen and Edinburgh, and also at the Linnean Society and Kew Gardens in London. The archives contain notes made in daily logbooks.

“Museum staff kept detailed records of the objects received and who had donated them. There is also correspondence in which offers were made from various quarters to collect specimens for the museum. Some mention their passion for science; others were obviously just out to make money.”

The material reveals myriad people and events that paint a vivid picture of how the collections were accumulated.

“For instance, there were the women who arrived at the museum early in the morning to light the fires, and the man whose job it was to take a puma for a walk around Edinburgh and the university area every day. It later ate birds belonging to the collection and had to be moved from the museum.”

The collections grew rapidly thanks to the efforts of the public, but it is also sometimes possible to discern disappointment among the staff over poor-quality specimens as they open a crate containing “yet another badly-stuffed zebra”. The collections influenced the British Empire’s self-image, and played a part in shaping natural history as a subject.

“Museums desired status, and wanted to exhibit specimens and objects from around the world. There was a particular cachet attached to uncommon specimens.”

The general public was also driven by a desire to be included in the scientific networks and to be able to correspond with a professor. Society at that time was deeply hierarchical, and not everyone enjoyed equal authority.

“Clergymen, for example, often contributed plants and other items, and they were sometimes disappointed when their name and contribution were not mentioned in publications.”

Present-day debate on citizen research

The project will not only shed new light on dissemination of Linnaeus’ ideas in new contexts in the 18th and 19th centuries. Another aim is to add to our understanding of contemporary citizen science.

“Nowadays when citizen science is discussed it’s often seen as a new development, but although the term itself is fairly new, the phenomenon has a long history. My research provides a deeper historical understanding, and also gives us some ideas about how knowledge is accumulated and spread in the present day.”

A topical example is how gamers playing computer games are helping researchers to analyze images of cells, increasing our understanding of how the immune system reacts to Covid-19. Other examples are monitoring of changes in bird populations or transcription of historical letters. But questions of hierarchy, status and trust are just as relevant today.

“Hopefully, historical perspectives can enrich the conversation about present-day citizen science, for instance in terms of ethical dimensions, and who’s knowledge and contributions count and are recognized,” Andersson Burnett concludes.

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo private, Wellcome Collection, Attribution 4.0 International, Wikipedia Commons, Marcus Marcetic