Ergang Wang

Professor of Polymer Chemistry

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, extension

Institution:

Chalmers University of Technology

Research Area:

Developing polymers for organic electronics

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, extension

Institution:

Chalmers University of Technology

Research Area:

Developing polymers for organic electronics

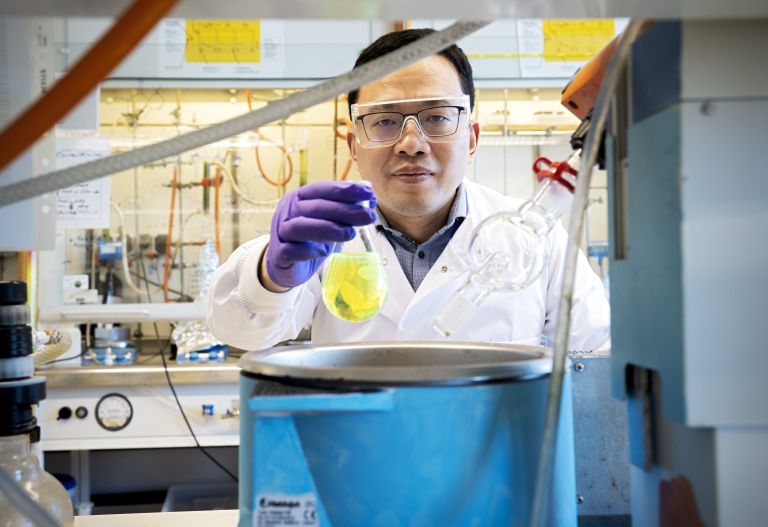

In recent years, Wang, a professor at Chalmers University of Technology, and his research team have developed semiconducting polymers: plastics with tunable electronic properties. The materials have many advantages: they are lightweight, transparent and easy to process. They can be used in solar cells, field-effect transistors and light-emitting diodes, for example. However, one problem remains: the polymers are difficult to recycle and do not decompose naturally.

Wang’s team is now addressing this challenge head-on. The goal is to create new semiconducting materials that combine the desired electronic properties of polymers with the ability to decompose at the end of their lifecycle. If successful, the idea is that such products could be buried in the ground and decompose within a few months – transforming e-waste from an environmental burden into a sustainable, circular solution.

”Huge quantities of electronic waste are generated every year, and the products are also difficult to recycle because they must be disassembled so the components can be utilized,” says Wang. He continues:

“As you may know, only ten percent of all plastics in the world are properly recycled. It is not hard to image that electronics – with their much more complex structures – are even harder to recycle. That’s why electronics made from biodegradable semiconducting polymers represent a critical step toward reducing electronic waste and enabling circular systems.”

The secret to making these materials biodegradable lies in using ingredients from nature: molecules or segments that break down naturally. Chlorophyll, which is abundant in nature, is one example. Together with Umeå University, Wang’s team have demonstrated light-emitting devices using chlorophyll extracted from spinach – rich in chlorophyll – a proof-of-concept showing how natural molecules can be used in electronics.

Within a few years, Wang hopes his team will have created a completely new class of biodegradable semiconducting polymers. He believes this could be an important contribution to a future transition from the age of plastics to an era of sustainable materials. But there are already many potential applications in the near term.

“One application is in biodegradable electrical implants, which could eliminate the need for surgery to remove the implant when it is no longer needed. Another is in health monitoring, such as internal body imaging. Instead of imaging via gastroscopy, which involves inserting a tube into the body, the imaging could be done via a pill containing biodegradable electronics that the patient swallows,” he says.

Electronics made from biodegradable semiconducting polymers represent a critical step toward reducing electronic waste and enabling circular systems.

He also believes the material could be used for remote-controlled sensors in nature to monitor the effects of a hazardous environmental spill, for instance. Since the equipment is biodegradable, it does not risk burdening the environment with hazardous waste.

Looking further ahead, there could even be a need to apply the technology to complex electronics like mobile phones, which today have an average lifespan of less than two years.

“It will take longer to realize that vision since cell phones contain various metals and highly complex electronics. But it’s not out of the question that solutions for mobile phones could be found in the future,” he says.

Wang’s curiosity about the research world began in childhood when a junior schoolteacher explained that research offers an opportunity to be creative and invent new things. As he grew older, he was inspired by a chemistry teacher who sparked his interest in chemical experiments and creating new components.

“As a researcher, I have the freedom to explore new and exciting realms. Every day brings new challenges in finding solutions and potential pathways. It’s also fantastic to have discussions with enthusiastic students and to hear their often brilliant ideas,” he says.

Originally from China, Wang has lived in Sweden for many years. He finds that research in Sweden is conducted in a strong and supportive collaborative climate, where colleagues are helpful and supportive. Receiving funding from Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation is a great honor, significantly improving the prospects for advancing his research.

“It’s fantastic to receive such long-term support without constraints on what I can do. It also enables me to recruit doctoral students and strengthen young researchers’ skills and competitiveness,” he says.

Text Ulrika Ernström

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Johan Wingborg