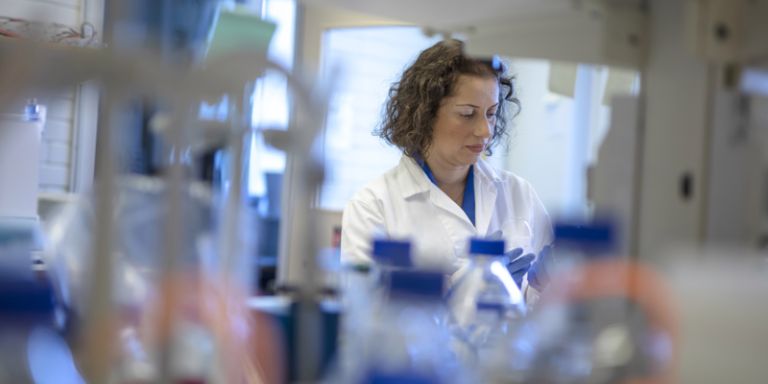

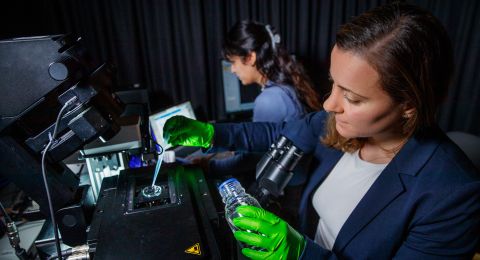

Nasim Sabouri has discovered proteins that regulate four-stranded DNA in the cell. Her findings are already forming the basis for efforts to develop new cancer therapeutics.

Nasim Sabouri

Associate Professor of Medical Chemistry

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, prolongation grant 2021

Institution:

Umeå University

Research field:

Chemical and biological properties of four-stranded DNA

Sabouri’s interest in four-stranded DNA began when she was a postdoc at Princeton University. This DNA is found in virtually all organisms, from viruses and bacteria to human beings, but had been little researched at the time.

When she returned to Umeå University and put together her own research team, she wanted to examine these DNA structures more closely. She soon realized that she was in uncharted territory.

Two unknown DNA structures

Human DNA is often depicted as a double helix. It breaks down into smaller units that include a nitrogen base: cytosine, guanine, adenine or thymine – C,G,A,T. The sequence of the nitrogen bases determines which of the body’s proteins will be synthesized.

It was long believed that the DNA double helix was the only structure formed in the cell, and that four-stranded DNA could only be formed in test tubes in research laboratories.

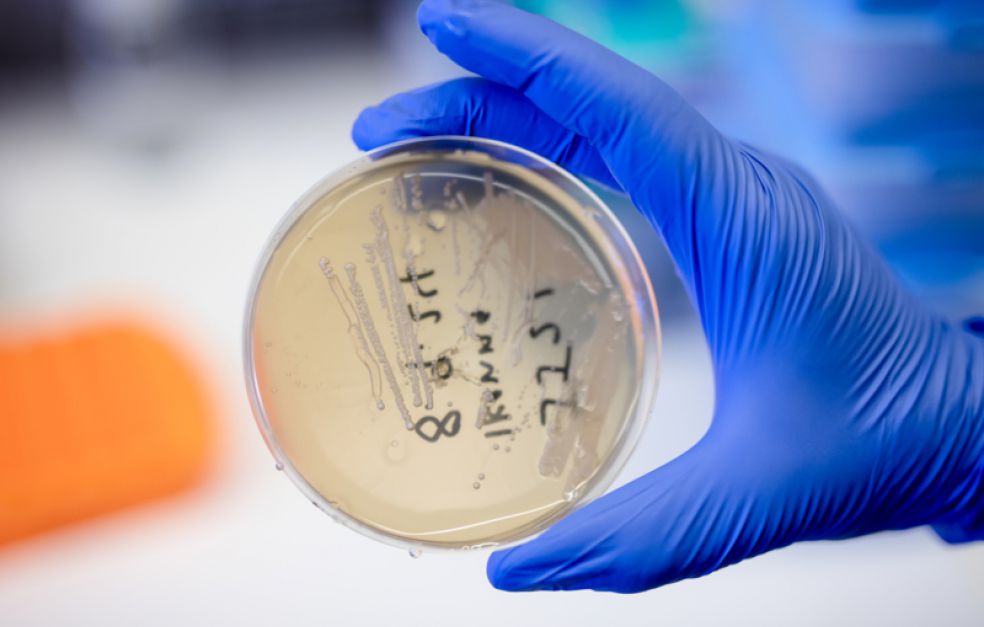

G-quadruplex (G4) was the first four-stranded stranded structure that Sabouri’s research team began to study. It forms when guanine bases from the same or different DNA strands interact with each other.

Latterly the researchers have also begun to study a DNA structure called “i-motif” (intercalated motif), about which even less is known. Its structure is formed in roughly the same way, but is made up of cytosine bases.

Both forms have been retained during evolution, which suggests they are of great importance to the cell. They are often found close to regions in the genome that activate or deactivate genes. They are also found in telomeres, i.e. at the ends of chromosomes.

“Their location in DNA suggests they play key roles in cell regulation,” Sabouri comments.

A correlation has also been identified between G4 and i-motif and the occurrence of cancer as well as neurodegenerative diseases such as Lou Gehrig’s disease (ALS).

“That’s why it’s so important to understand how four-stranded DNA works and which molecules regulate it.”

At first all experiments were performed on yeast – a single-cell mechanism that grows quickly. It also has DNA that is easy to manipulate.

After a time the model could be transposed onto a line of human cells. The project has recently also begun a collaboration with a team researching on zebra fish.

The researchers have now developed a method of studying the structures using fluorescent molecules.

“It’s taken a long time to optimize our methods. We have developed an array of tools for model organisms as well as human cells.”

“I have been given the chance to advance a new and exciting field of research with the aim of developing more efficacious cancer therapies.”

New type of cancer treatment

Sabouri was chosen as a Wallenberg Academy Fellow in 2015. Her grant has since been extended for a further five years. A central aim of her research is to identify proteins and protein domains that bind to four-stranded DNA.

“We want to find out which proteins are capable of resolving these stable structures that can damage DNA if they remain unresolved. We want to obtain a detailed picture of the proteins that regulate four-stranded DNA, and how they can be linked to the progression of certain diseases.”

The process of translating the findings into clinical utility is already in full swing, in collaboration with a company called Umeå Biotech Incubator AB.

“We hope to develop a new type of chemotherapy for various forms of cancer.”

Finding time with the help of strict daily routines

Sabouri was born in Iran, grew up in Täby (just north of Stockholm), and moved to Umeå in the north of Sweden to study for a PhD in medical chemistry. Her doctoral thesis, published in 2008, described how the enzyme DNA polymerase can bypass damaged DNA during the replication process.

Her research places her on an international stage, but in her private life she has both feet firmly on the ground. She has three young daughters and lives on the outskirts of Örnsköldsvik, close to the farm that her husband has inherited and now runs.

This particular day she got up at six, gave her children breakfast and took an early train to Umeå.

“On the train I checked my e-mails and went over a presentation I was to give before lunch.”

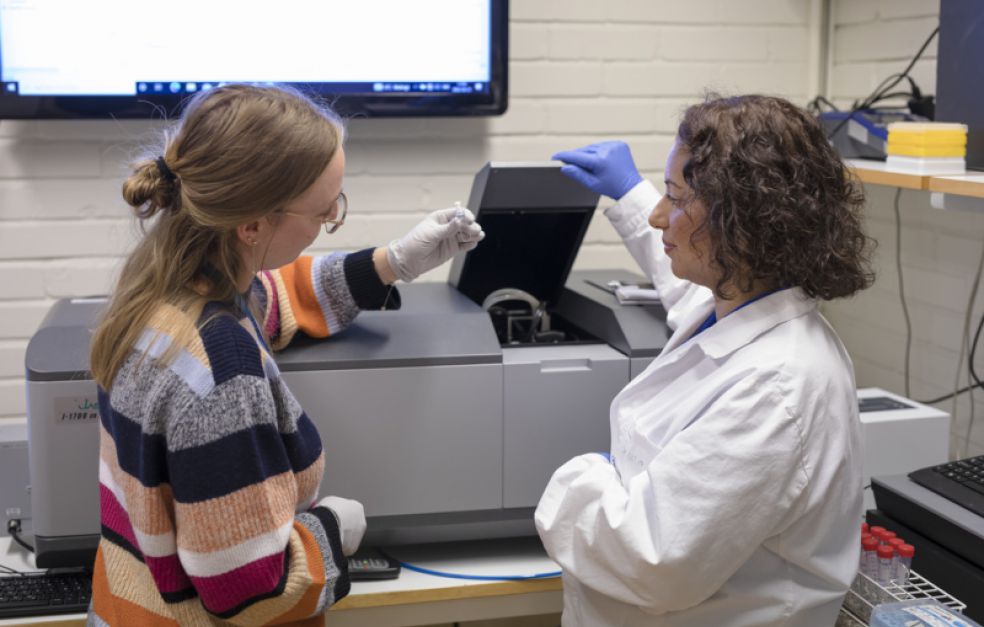

After a short walk from the station to the university, her first port of call is a meeting with the head of department, following by another with her research team.

“Everyone presents what they’ve done during the week. We discuss all results in great detail and talk about how we should interpret them and how to proceed.”

Since January 1, 2022, Sabouri has been both director of doctoral studies and deputy head of department. She has created well-defined routines to ensure she still has enough time for research. Each day she jots down what she needs to do on brightly colored Post-It Notes before she takes the train home.

In her leadership role she sees all her colleagues as individuals.

“With some students I have to be very much a leader; others don’t need as much supervision. When an experiment has failed, I try to find a new approach, and when things go well I usually say something positive. Encouragement is essential. We usually celebrate with Champagne when one of our articles is accepted for publication.”

Text Carin Mannberg-Zackari

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Mattias Pettersson