The lymphatic system is one of the body’s largest organs. Yet it has long been neglected in research, having been largely regarded as a passive drainage system. But in recent years researchers have realized that the lymphatic system holds many secrets, and plays a key role in the body’s immune system and in various diseases.

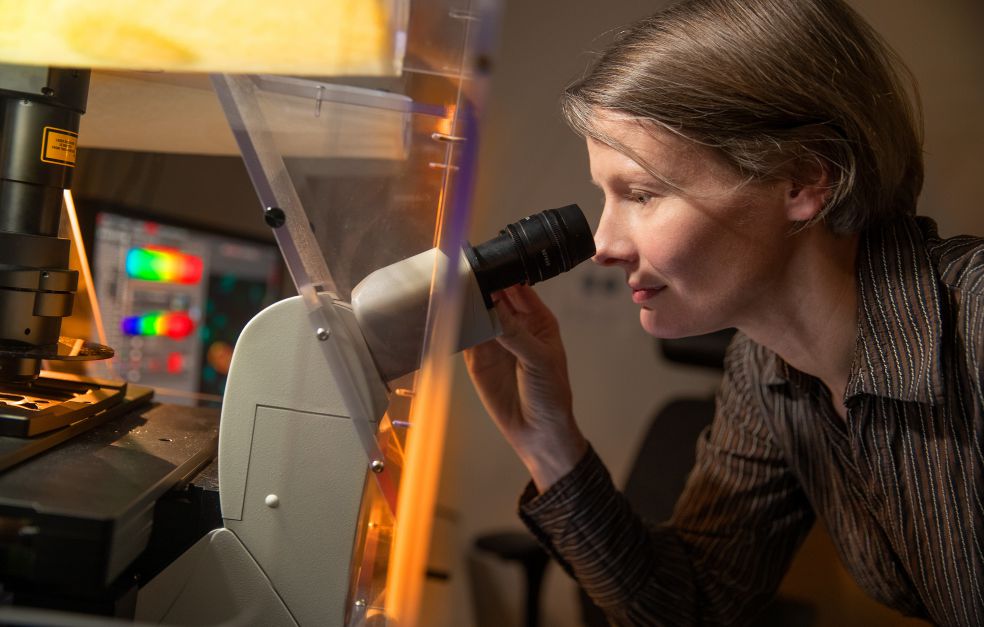

Taija Mäkinen

Professor

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

Vascular biology, particularly regulation of the lymphatic system, and understanding how lymph vessels are formed at molecular level and in living organisms.

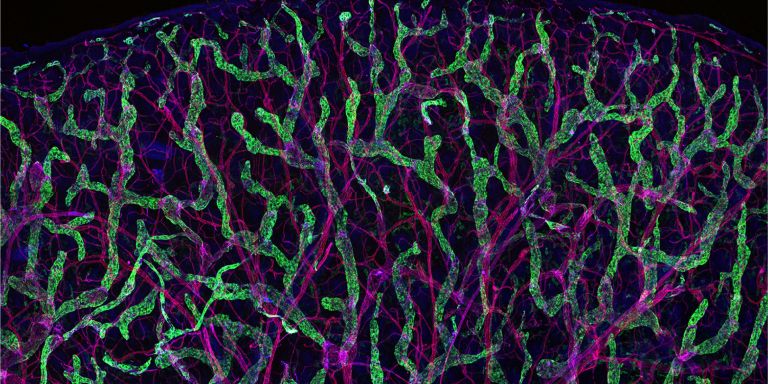

The lymphatic system is a vascular system existing in parallel with the blood vessels. The system reaches into almost all tissues in the body via networks of small tubes. One of its main functions is to carry fluid from the tissues back into the blood, thereby maintaining a stable fluid balance. In recent years research has shown that the lymph vessels are involved in many other processes in the body, and impact various diseases. But we still know little about the biology of the lymphatic system.

Taija Mäkinen is a Wallenberg Scholar, and wants to explore the lymphatic system. She is drawn to the mysterious and the unknown, where access to advanced microscopy is needed to reveal fundamental mechanisms.

“I still recall how fascinated I was as a child when I received my first magnifying glass as a present, and was suddenly able to see details invisible to the naked eye. It’s no coincidence that I now find myself working in a field involving the use of various imaging techniques. And I love the beauty revealed in the images.”

In truth, she could imagine studying any organ system.

“I am interested in developmental processes in general, and how cells in the body interact, communicate, and manage to form so many different specialized organs.”

Lymphatic system discovered by a Swede

During her time as a PhD student at Helsinki University Mäkinen was introduced to the subject by her supervisor, a leading expert in lymphatic biology. As a postdoc at the Max Planck Institute in Munich, she moved on to neurobiology, but returned to lymph vessels when she started her own research team in London. She has been based at the Rudbeck Laboratory at Uppsala University since 2013.

“It’s a happy coincidence, since Olof Rudbeck is one of the discoverers of the lymphatic system in the 1600s.”

She is now devoting all her energies to understanding how the lymphatic system works at molecular level. A key element is to identify unique properties and functions of lymph vessels in different tissues, and ascertain the genes that regulate vessel formation. Among other things, the research is based on mouse models, which are then combined with cell culture studies and single-cell RNA sequencing.

“We now know that the lymphatic system is much more complicated than had been thought, and that it plays an active part in the development of various diseases, including cancer and auto-immune diseases.”

“Being chosen as a Wallenberg Scholar gives me great freedom, and enables me to explore questions that might not be possible to answer in the short term. I also see the grant as recognition of the research findings we have already made in this field.”

For instance, lymph vessel formation in a tumor enables the cancer to spread to the rest of the body via lymph vessels. And the lymphatic system has been found to modulate various functions in the immune system, sometimes with detrimental effects. Endothelial cells, which make up the lymph vessels, can also affect the function of the immune system’s T-cells, that normally attack the cancer cells, thereby allowing the cancer to grow. But Mäkinen hopes it will be possible to use this knowledge to develop new forms of immunotherapy in the future.

Enormous suffering

In addition to common diseases, there is a group of genetic diseases that are associated with the lymphatic system. One example is that of lymphatic deformities, where excessive, almost tumor-like, growth of lymph vessels occurs. Another is lymphedema, usually caused by an absence of lymph vessels and normal function.

Here, too, there is a need for more research; the diseases are not taken seriously, even though they can cause great suffering. During her time in London Mäkinen collaborated with a clinic for patients with lymphedema. It changed her perspective.

“Many people believe that these problems are merely cosmetic, but patients with these swellings can find themselves in dramatic situations involving a great deal of pain. They often contract infections, which may lead to amputation – and there is no cure.”

This is another area in which Mäkinen hopes that research will benefit sufferers. For example, her team has succeeded in modelling exactly the same mutation found in patients with lymphatic deformities in a mouse.

“It enables us to study both the function of the gene in normal development, and various pathological processes. We aim to use this model to test various treatment strategies.”

The brain yields surprises

Mäkinen is pleased that interest in the lymphatic system has taken off in recent years. There is now a steady stream of new publications and unexpected discoveries. One of the most surprising is that the lymphatic system extends all the way into the brain.

“It was thought that lymph vessels were completely absent from the brain, but researchers, including my PhD student supervisor, have now shown that lymph vessels are in fact present in the meninges.”

Follow-up studies indicate that the meningeal lymph vessels may play a part in both neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory diseases, since they control the movement of immune cells out of the brain.

“It reminds us of the fundaments of basic research – to keep an open mind, and have the courage and persistence to spend time researching the fundamental issues.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström