In 17th- and 18th-century Sweden women did demanding physical work, such as chopping firewood or transporting goods. Meanwhile, men might be looking after children or weaving baskets. These findings have emerged from a unique database about working life in the past compiled by historians at Uppsala University. Their research puts paid to long-standing notions about how women and men supported themselves going right back to the time of Gustav Vasa (King of Sweden 1521–1560), and may provide insights into the Swedish model of the 20th century.

Maria Ågren

Professor of History

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

The interface between social history, legal history and economic history, including the ways people have supported themselves, and the view of land ownership in the early modern era, with a gender perspective.

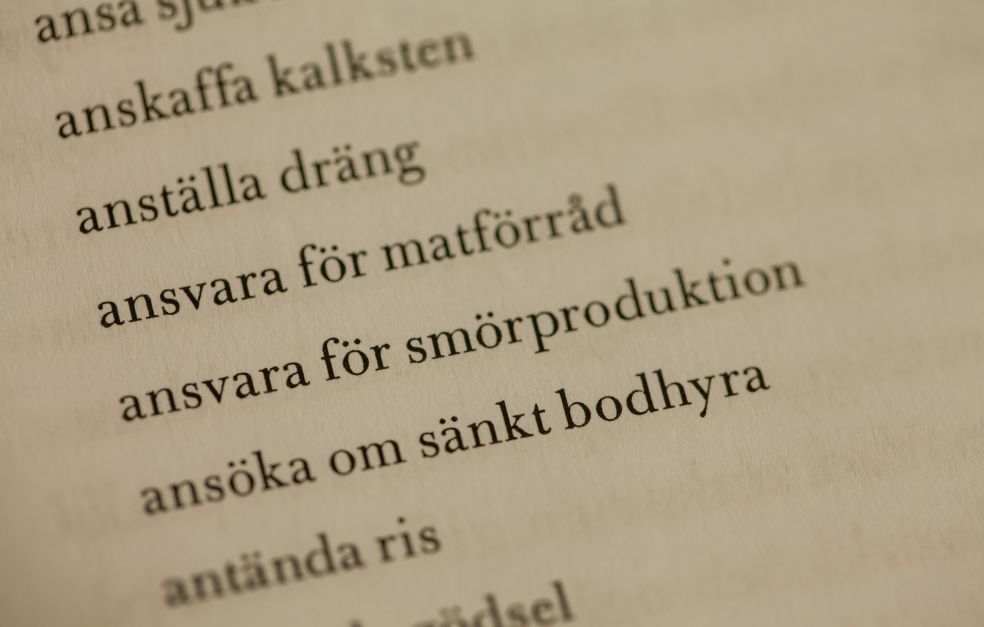

Over the past few years historian Maria Ågren at Uppsala University has led a project to build up a database on working life in Sweden in centuries past. The researchers engaged in the Gender and Work (GaW) project have collected over 30,000 verb phrases vividly describing work in former days, such as “minding children”, and “chopping firewood”. The quotes come primarily from historical court records, and provide an authentic insight into how people spent their days.

“We have developed what we call ‘the verb-oriented method’. The point of collecting and studying verb forms is to gain an idea of what people actually did, not merely what their occupational titles were.”

One problem with occupational titles, expressed as nouns, is the lack of specifics about people’s work tasks.

“People could have the title ‘cobbler’ or ‘mayor’, but do something quite different in practice. The same applies today. My own title is ‘professor’, but it doesn’t really say anything about how I spend my days.”

The historians also face the difficulty that women hardly ever had titles in this bygone age. A new and innovative method was therefore needed to throw light on the working lives of women. The verb phrases enable them to open a door to this unknown world.

“We’re finding both men and women in all types of work – men caring for other people, and women working in the forest or transporting heavy goods. Previous research presumed that men and women lived and worked in separate spheres, but our findings suggest this is not so, at least not in Sweden.”

Married/unmarried?

One key finding is that the main dividing line in the 17th century was not between the sexes. No – the most important variable was marital status. Thus, the differences in work done were greater between married and unmarried people than between men and women. A married person had access to resources, and could decide over the work done by others. This also explains the heavy emphasis on marriage in bygone days – as a way of progressing by becoming head of a household.

“We expected to see that married women had a greater position of power than unmarried women, but this pattern is seen extremely clearly in the extensive material we have gathered, and we were surprised by the force of our findings,” Ågren says.

“Being backed to carry out this project is my most fantastic experience as a researcher. We will be able to work on a large scale and in teams, which is rare in the humanities. The normal situation is for researchers in these fields to work alone.”

New microdata from the 1800s

The first phase of the GaW project was confined to the period 1550–1799. The research is now being extended to a partly overlapping period, 1720–1880, which stretches from the time around the death of King Karl XII to the rise of the labor movement.

The researchers are delving deeper in a limited geographic area – the town of Västerås and the surrounding rural area. The aim is to see whether marital status remains the key variable. Studying a smaller area will enable them to search for people mentioned in court records in church archives, and verify whether or not they were married.

Ågren wants to examine the relationship between norm and practice. The late 18th century saw the establishment of ideas that emphasized differences between men and women, almost as though they were two separate species. By the 19th century this had resulted in new ideals of masculinity and femininity, mirrored by depictions in the press and literature. It is hoped that further data gathering will reveal whether these new intellectual goods impacted day-to-day life.

“One important question about the 19th century is whether there was a shift between masculine and feminine roles in the sphere of work, or whether marital status, rather than gender, continued to define differences in patterns of work.”

The scale of the project is unusual in the humanities, and has been made possible by a Wallenberg Scholar grant extending over ten years. Findings from the project are now being disseminated via conferences, and have already had an international impact.

“Research teams in other countries have been inspired by the project, and are using our methods.”

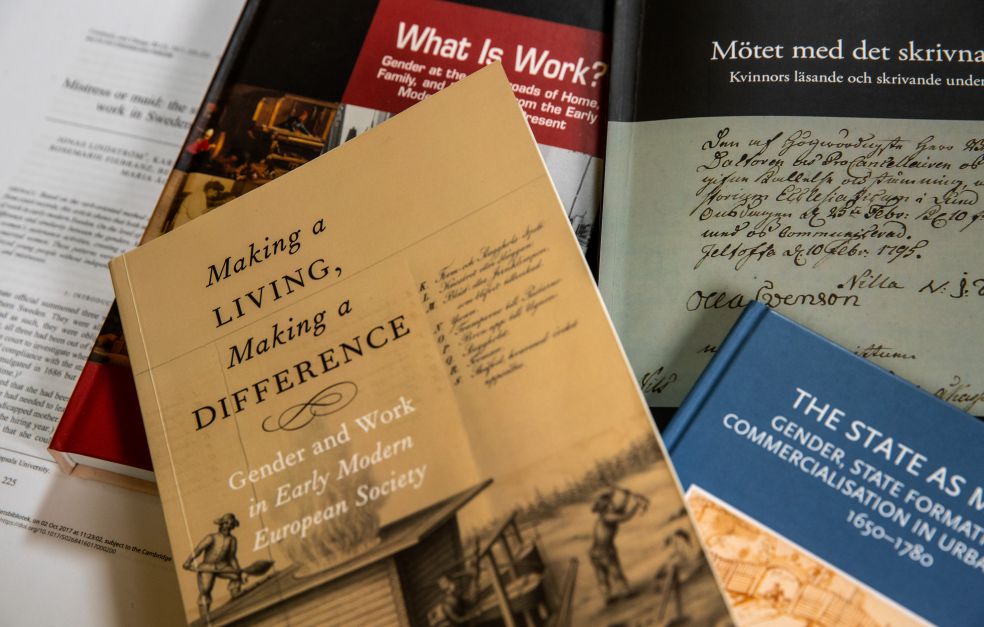

Historical clues to the balancing act of modern life

Ågren and her research team have written a book entitled Making a Living, Making a Difference, which is a seminal account of their research and methods. Another book by Ågren, The State as Master, is a close-up study of families in the 18th century, in which the men were employed as customs officials. Formally speaking, women could not be employed by the state, but the study shows they were nonetheless involved in the men’s work, for example by collecting customs duties from farmers at the customs gates. Meanwhile, men took on duties that we often regard as women’s work, such as taking the children to the customs house and looking after them while performing their regular office work.

Parallels can be drawn with the balancing act of modern life, and Ågren believes that the Swedish model of the 20th century is rooted in earlier times.

“I think there may be interesting domestic roots leading to the greater equality and flexibility that we see today in Sweden.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström