Funding under the Life Science initiative

The projects involving research on forest biology, forest genetics and forest production have been awarded grants within the scope of the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation Life Science initiative, and will run for ten years at a number of higher education institutions.

Principal investigators:

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences

Professors Ove Nilsson

Tomas Lundmark

Uppsala University

Ulf Gyllensten

Science for Life Laboratory in Stockholm and Uppsala

Co-investigators:

Forestry Research Institute of Sweden

Grant in SEK:

SEK 315 million over ten years

(2019-2029)

Almost three-quarters of Sweden’s surface area is covered by forest, mostly coniferous. Forestry has always been central to the Swedish economy, and there is much to suggest that its importance will grow. The transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources will bring an increased demand for forest raw materials. Meeting that demand will require more efficient forestry and a higher forest growth rate, while still meeting exacting environmental standards.

A coherent research initiative combining basic and applied research has started in collaboration between the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Umeå University and SciLifeLab in Stockholm and Uppsala.

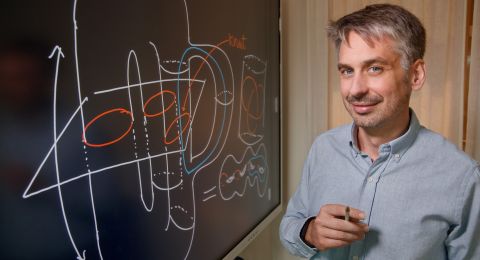

The aim is to adopt a holistic approach to forest growth from every conceivable angle. Projects concerning conifer DNA, forest biotechnology and forest genetics are being coordinated by Professors Ove Nilsson at SLU in Umeå and Ulf Gyllensten at Uppsala University.

Tomas Lundmark, a professor at SLU in Umeå, is heading projects in the field of forest production and forest management.

“It’s been difficult to obtain funding to develop forest management for higher growth, so we were delighted to hear we had received the grant. It gives us great scope to research and develop forest management as cultivation systems,” Lundmark says.

The projects, which have received funding from Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, will run for ten years at a number of higher education institutions.

“It is without doubt one of the largest research grants we have seen. The long time span makes it unique. It takes time to develop techniques for tree breeding, since trees have long growth stages. Now we can invest both in infrastructure and in expertise over the coming ten to fifteen years,” comments Nilsson.

Mapping pine DNA

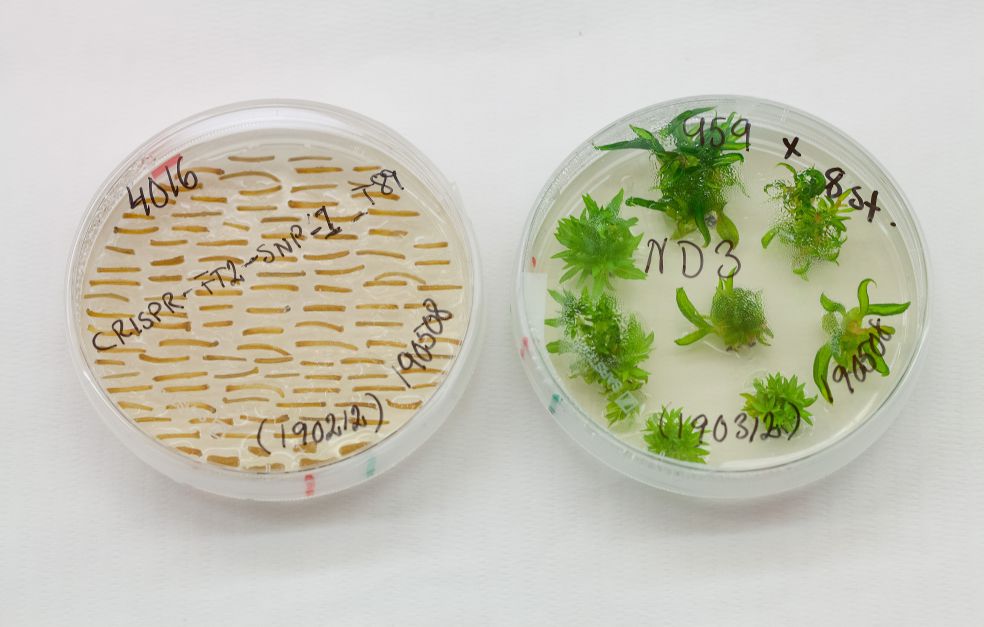

The Swedish spruce genome was mapped in 2013 by researchers at Umeå Plant Science Centre (UPSC). They are now proceeding to make a more detailed update. They will also be mapping the Swedish pine genome for the first time.

“Mapping the spruce genome was highly complicated, since its DNA is so huge and complex. We only just managed it. Technical developments since then have enabled us to go on to examine not just a single spruce in more detail, but also the genetic variation in all spruces,” says Nilsson.

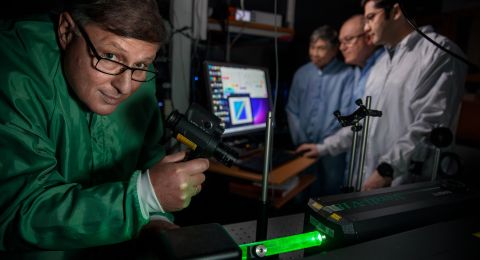

Some 40 research teams at UPSC will be examining the genes that control tree growth, development and adaptation in the forest environment. The researchers are collaborating with the Forestry Research Institute of Sweden as they attempt to identify natural variations in the DNA of thousands of spruces and pines in the Swedish conifer breeding programs. DNA sequencing is being performed at SciLifeLab.

A new generation of trees will be evaluated using a fully-automated “phenotype” unit at Umeå. The unit is a glasshouse, in which hundreds of trees are cultivated on conveyor belts under controlled conditions. Water, nutrients and light are supplied automatically at various stations at which the young trees stop. There are also stops where the length, circumference and other individual characteristics of the trees are recorded.

Tomas Lundmark examines a table of spruce and pine seedlings with keen interest, reflecting over whether more basic science in forest management research offers potential for new insights:

“At present, much forest management is based on long-term field studies. If we can combine observations in the forest with basic scientific experiments, we will be able to acquire new knowledge more quickly. If Ove provides new seedlings and saplings possessing the best possible characteristics, I will look after them in the best environment and in the best way. Together, this may lead to substantially higher rates of growth in the forests of the future, which will be needed if we are to wean ourselves off our dependency on oil.”

Breaking new ground

The research initiative combines basic science with more applied sciences in a way never before seen.

“Collaboration sounds pretty obvious, but there has been a yawning chasm between our fields. If we are to maximize the potential of our findings about genes and their properties, and how that knowledge can be used to breed a completely new generation of trees, they must be given the best possible growing conditions. In addition, improved knowledge about how trees grow will be needed to develop new management methods,” Nilsson says.

Many of the processes controlling growth take place underground. New findings on interaction between trees and fungi and microorganisms, as well as competition between trees, will inform new forest management programs.

“We have discovered that we can borrow tools from basic research to answer questions about forests. Things in my world that were impossible only a year ago can now be done. For instance, we can take a soil sample, remove roots, take a DNA sample of a root, and find out where the part of the tree that is above ground level is located,” Lundmark explains.

Ove Nilsson thinks that climate and environmental changes will necessitate a more flexible approach to forestry.

“We will be moving away from standard protocols to more individualized solutions. Changes are occurring so rapidly, and forests cannot adapt quickly enough and still deliver raw materials. We have to find trees that can cope with new diseases and a warmer climate,” he says.

Lundmark points out that society cannot afford to wait for forests to adapt on their own:

“The whole idea of forest management is to take action to counter undesirable effects, and achieve desirable ones. When the market cries out for more renewable products we must be able to offer alternatives.”

Text Carin Mannberg-Zackari

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström