Project Grant 2022

Resolving the anti-tumor effects of tertiary lymphoid structures

Principal investigator:

Professor Göran Jönsson, Lund University

Co-investigators:

Lund University

Joan Yuan

Kristian Pietras

Institution:

Lund University

Grant in SEK:

SEK 31 million over five years

Each year some 4,300 Swedes develop melanoma – an aggressive form of skin cancer. If it is discovered early, virtually all patients recover once the tumor has been removed. But if the cancer has spread, the prognosis is much worse. For many years chemotherapy was the only weapon doctors had against metastatic melanoma, but it works in only about five percent of cases. For the past ten years or so the most serious cases are now treated with “checkpoint blockers”, a type of immunotherapy that strengthens the ability of the immune system to fight cancer cells. It works much better – but still only helps around half of melanoma patients. The Lund researchers have found a clue as to why this is.

“There is a great deal of research in this field, usually concerning immune system T cells, since the belief has been that they determine whether or not immunotherapy will work. We studied another cell type – B cells – and saw that they often gather in specific structures in tumors in patients who responded well to immunotherapy,” Göran Jönsson says.

He is a professor of medical research at Lund University. Some years ago his team discovered the link between immunotherapy and the clusters of B cells, whose real name is tertiary lymphoid structures. It is as though there are tiny immunological factories in which T cells are programmed to be more effective, and new B cells are formed that can produce antibodies against the tumor cells.

A better understanding of the clusters

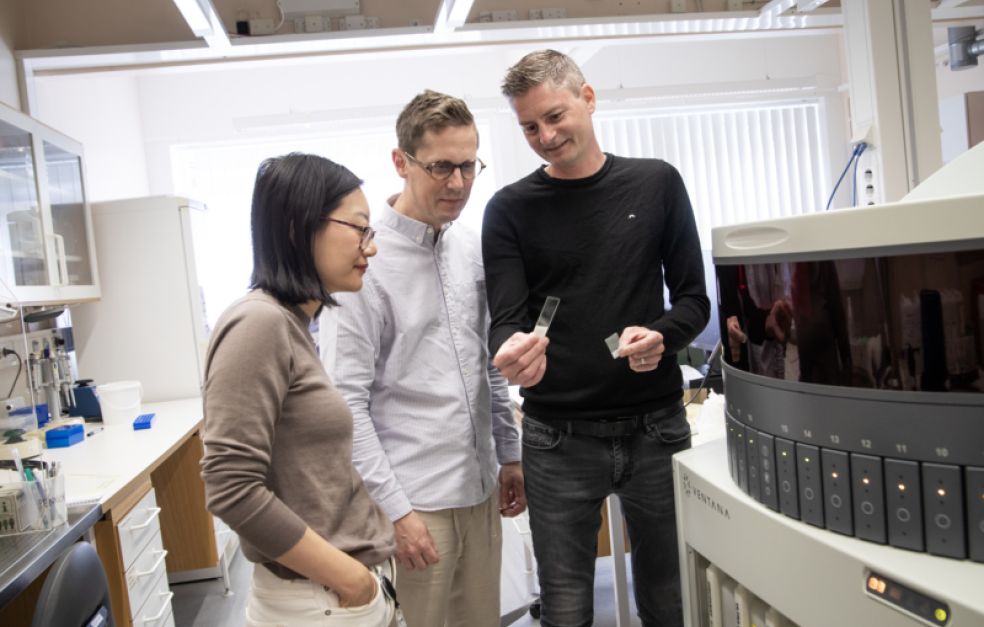

Jönsson is joint head of a project funded by Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation in which he is working in Lund with experts in other fields to study B cell structures more closely.

“We want to understand how these structures are formed and exactly what they look like inside the tumors. We’re doing this by studying tumor material from patients, and also by trying to create the structures in mouse models,” Jönsson explains.

The other researchers heading the project are Joan Yuan, researching in developmental biology, who has developed multiple mouse models to study B cell development, and Kristian Pietras, professor of translational cancer research, who is studying another type of cell – fibroblasts – in mice. Fibroblasts are support cells that have been found to play a key role in the formation of B cell clusters.

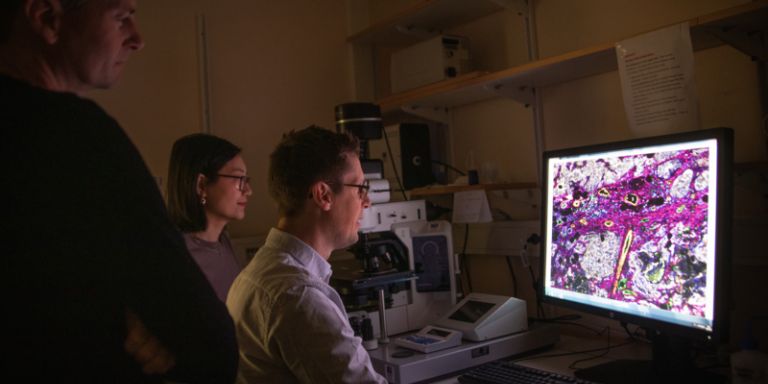

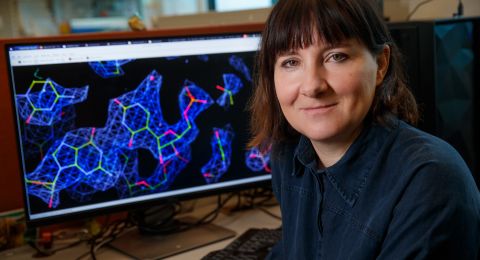

The researchers are now using various techniques to see what happens both in human tumor material and in mice. They are using single-cell sequencing for in-depth analysis of an individual cell’s content of DNA, RNA or proteins, and spatial sequencing, which enables them to ascertain the location of different cells and molecules in the tumor.

Mouse models and human tissue

“We’re using the mouse models to gain a more detailed understanding of the mechanisms. We will then turn our attention to the material from human tumors and see whether we find the same mechanisms there. We’ll also try to use what we learn from the human material for modeling in mice, to induce them to form the B cell structures we’re interested in.”

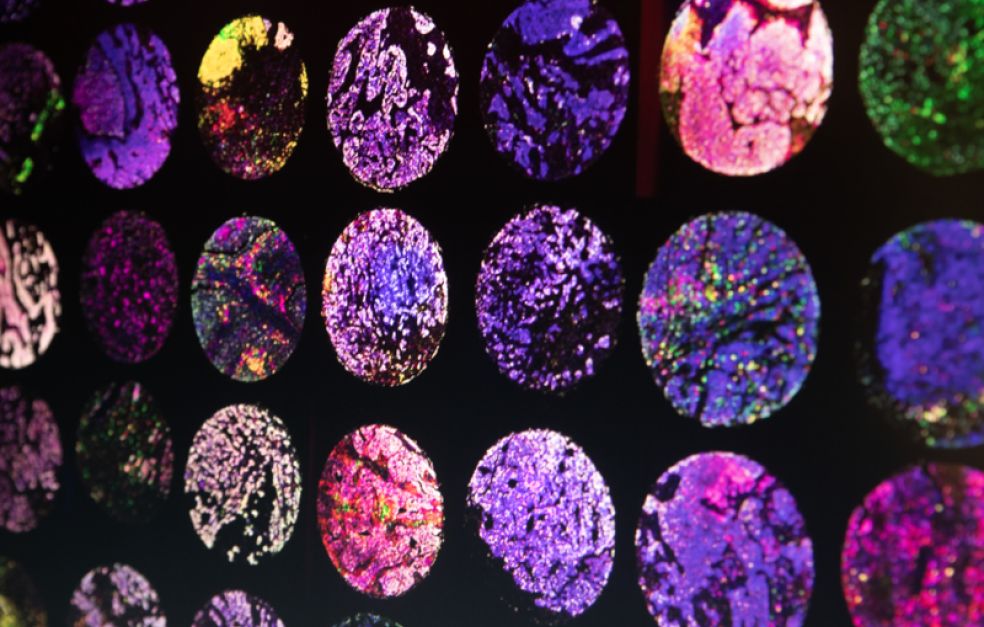

There are a number of B cell variants in the body. Some of them form antibodies; others have the job of identifying material from suspected cells or infections so that the immune system can go on the attack. The researchers hope to control the cells in mice that are present and active in the clusters, so they can find out which of them are key to the success of immunotherapy. They will also be determining the factors distinguishing mature B cell clusters from less mature ones, which are also common in melanoma tissue, to see whether they have different functions.

Cluster formation triggered by a combination of cells

It may be possible to find a substance in the body – a biomarker – whose concentration indicates whether or not the patient has developed B cell clusters. If so, the biomarker could be used to assess whether or not a patient will benefit from the therapy. But most of all, it would be helpful to find a way of driving the formation of the clusters so more patients can be helped by immunotherapy. The researchers in Lund believe formation can be triggered by signals from multiple different cells: possibly a combination of tumor cells, immune cells and vascular cells. They liken it to the formation of another structure in the immune system, i.e. the lymph nodes, where the cell signals needed for them to form are fairly well known. The human tumor material used by the researchers comes from metastases in the lymph nodes, and the B cell structures appear to form more easily there than elsewhere.

“I think our respective fields of expertise in the project complement each really well. Our ability to combine such advanced mouse models and genomic techniques enables us to obtain large quantities of extremely useful information. This has been made possible by the collaboration between the three teams,” Jönsson says.

Text Lisa Kirsebom

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Åsa Wallin