Project Grant 2012

The gut metagenome as a novel target to treat childhood obesity

Principal investigator:

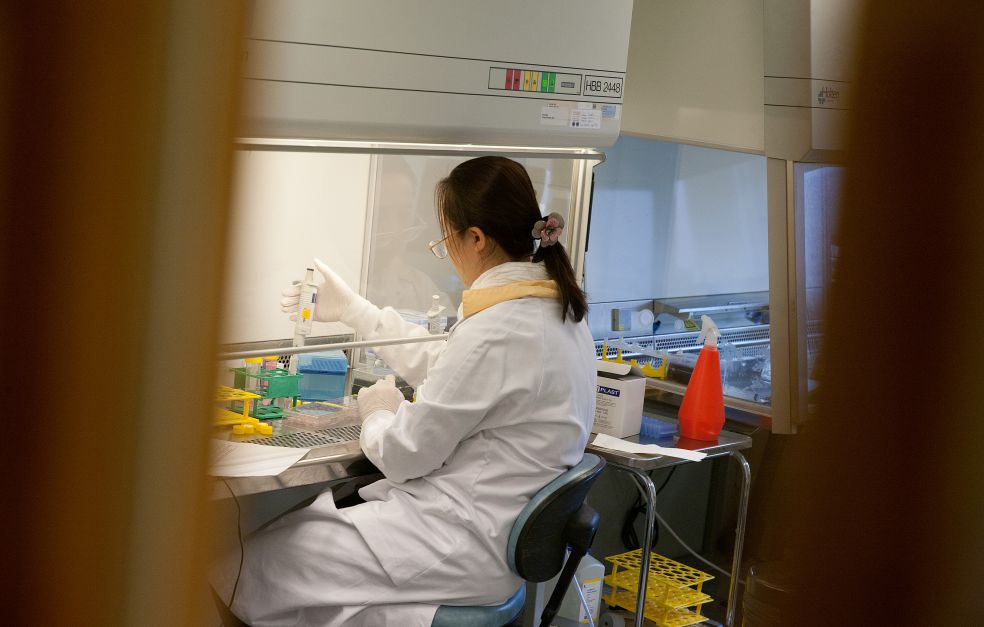

Fredrik Bäckhed, Professor of Molecular Medicine, especially the role of the microbiota in metabolism

Co-investigators:

Jovanna Dahlgren

Institution:

University of Gothenburg

Grant in SEK:

SEK 30.8 million over five years

“The dream scenario is to develop a probiotic, a bacteria culture, which can be provided to children who lack the protective bacteria. It could be administered as drops, like vitamin AD drops, in capsules or in yoghurt,” says Professor Fredrik Bäckhed the Director of Wallenberg Laboratory for Cardiovascular and Metabolic Research.

Because the microbiota develops from birth and in the first years of life, it may also provide a window of opportunity when it can be manipulated.

Overweight and obesity are a runaway health problem in large parts of the world. Too much sedentary behavior and junk food is the most common explanation. But since the beginning of the 2000s, the researchers have begun to be increasingly interested in the significance of the gut microbiota as a contributor to development of obesity and other so-called lifestyle diseases.

“It was when I worked together with the American researcher Jeff Gordon and discovered that germ-free mice did not develop obesity and that profiling the gut microbiota through sequencing got more affordable and readily available the field took off.”

Map of the establishment of the gut microbiota

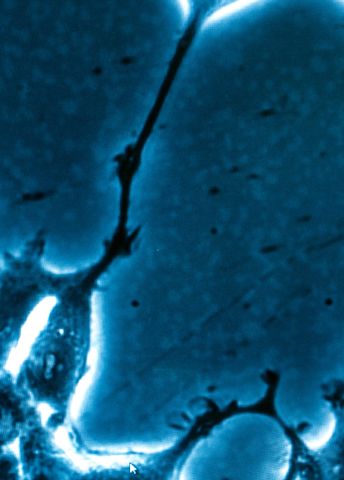

The intestines contain ten times more bacteria than cells in the human body. Some bacteria are beneficial while others can cause disease if they are provided too much space. Together, they form an inner ecosystem.

“The significance of the normal microbiota has been forgotten, it was popular to study in Pasteur’s time. However, it is also much more difficult to study compared with the pathogenic bacteria, bacteria that cause disease such as Salmonella.”

Fredrik Bäckhed’s interest in the connection between the microbiota and childhood obesity was incited by Jovanna Dahlgren and Josefin Rosvall, physicians and researchers at Queen Silvia’s Children’s Hospital, who set up a study of childhood obesity in Halmstad.

“They studied 3,000 children who were born during one year and they concluded that the microbiota was a factor of interest.”

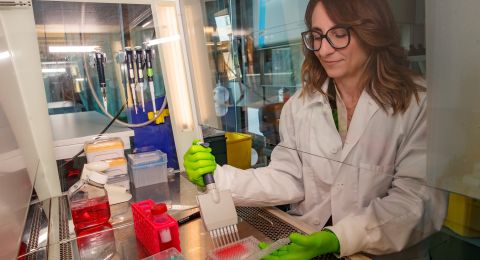

In 2008, a sub-study was initiated with 520 children, of which 120 were born by C-section. Vaginally born children get the mother’s stool in them while children born by C-section get skin bacteria in them. A register was set up with facts about breastfeeding, formula feeding and stool samples from mothers and children at birth. Samples were also collected after four months when they began eating samples of food, at 12 months when most had stopped receiving breast milk, at three years and five years of age.

“We are creating a map over how the microbiota develops from birth to the age of five. Because overweight and obesity are relatively common, we expect that several of the children in the group will develop childhood obesity and that this set up will allow us to determine whether the gut microbiota is altered before the onset of disease.”

Lack protective bacteria

Such prospective studies take time so in order to demonstrate a causal relationship, experiments were also initiated with germ-free mice.

“The objective is to determine the development, composition and function of the gut microbiota. By colonizing germfree mice with gut microbiota from lean and obese children we may identify bacteria that are connected to leanness or obesity and explore whether it also modulates the fat storage in mice.”

The researchers’ hypothesis is that children who develop obesity lack bacteria that lean children have.

“In adults, the collective knowledge indicates that the obese have a less complex microbiota than thin people. Our hypothesis is therefore that early disturbances in the gut microbiota may have consequences later in life.”

What is cause and effect?

Hence, the researchers know that the microbiota differs, but the question is what comes first, the chicken or the egg?

“We do not yet know if the gut microbiota causes obesity or if obesity affects the gut microbiota. We therefore believe that the animal experiments and the monitoring of children over time, in other words even before they develop obesity, can contribute to understanding if the microbiota directly contributes to obesity.”

Fredrik Bäckhed believes that Gothenburg is a perfect place for studies of the gut microbiota since there is a well-established cooperation between researchers, doctors and patients.

“It was a strategic choice to establish my laboratory here. Patients with cardiovascular disease and diabetes are continuously followed in studies and since we hypothesize that there is a connection with the gut microbiota in diabetes as well, it is a major asset

Diseases like celiac, asthma, allergies, type-1 diabetes and colic also have connections with the microbiota.”

The research team also collaborates with a team in Copenhagen and one in China.

“The project grant from the Wallenberg Foundation means that we can focus entirely on the science for five years. The results are completely up to us and the hypothesis, and it feels very inspiring.”

When the study is concluded in 2018, the oldest children involved will be 10-11 years old.

“It would be incredibly interesting to follow them all the way up to the age of 60 to look at cardiovascular disease, among other things,” says Fredrik Bäckhed.

Text Carina Dahlberg

Translation Semantix

Photo Magnus Bergström