In the past ten years, Mathias Uhlén has led one of the largest scientific projects in Sweden's history: mapping all of the proteins in the body. The project has generated an enormous bank of data. As a recently named Wallenberg Scholar, he now wants to delve into all the details and create a comprehensive picture of the body's fantastic machinery. The challenge is to turn data to knowledge.

Mathias Uhlén

Professor of Microbiology, KTH Royal Institute of Technology; Professor of Molecular Bioscience, Technical University of Denmark

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

KTH Royal Institute of Technology and Technical University of Denmark

Research field:

Creating an atlas of all human proteins.

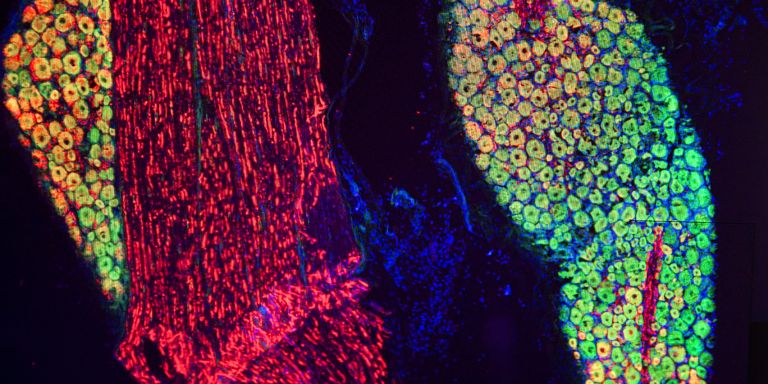

What is it that makes a kidney a kidney? And what makes a heart a heart? All cells, regardless of whether they are in a kidney or the heart, contain exactly the same genetic material and genes. However, different genes are active in the various cells. This leads the cells to have entirely different functions. Some become nerves, others begin to produce insulin. If researchers are to understand how our bodies work, it is these differences they need to begin to establish.

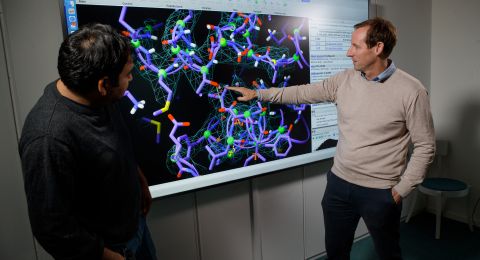

Mathias Uhlén, Professor of Microbiology at KTH Royal Institute of Technology, has focused on this in particular in the past ten years. He has conducted the gigantic »Human Protein Atlas« project, a mapping of all human proteins. Every gene is a code for what a protein will look like. Since it is the proteins that account for all activities in the body. They build muscles and tendons, catalyze chemical reactions, send signals all over and much more.

In the Human Protein Atlas Project, researchers have mapped what organs the various proteins are in. Today, they have collected data on around four fifths of the body's more than 20,000 proteins.

“It has been a bit of a factory. Now what I would like to do is to take a step away from all the details and try to understand human biology in a more holistic manner. If we compare it with a car, for instance, it might take 10,000 parts to make a transmission. I want to understand in the same way what the list of ingredients looks like, for example, for a kidney or a liver,” says Mathias Uhlén.

All cells are surprisingly similar

One of the insights that has grown forth through the Protein Atlas Project is that the majority of all of the body's proteins are present in all cells.

“When I began this project ten years ago, I thought that the proteins such as those that are in the heart would differ from those in the brain. But what is becoming increasingly clear is that few proteins, only around 10%, are tissue specific. These are more an exception than a rule. More than half of all proteins are expressed everywhere in the body,” says Mathias Uhlén.

He believes in hindsight that this might have been able to be foreseen. A very large number of the genes we have are also in very primitive organisms like fruit flies or yeast cells. All cells, regardless of organism, use related genes to generate energy or repair their genetic material. These necessary genes are sometimes called "housekeeping genes". They stand for the routine maintenance.

This insight, that the body's cells are more alike than different, plays a major role for the development of new medicines.

“This has major consequences. If a medicine against a protein that is involved in kidney disease is being developed, these proteins may also be in the brain. This can have serious side-effects,” says Mathias Uhlén.

This also explains why so many of our current medicines have side effects.

"Wallenberg Scholar is the finest award one can receive as a researcher in Sweden. It shows that what you do is appreciated among colleagues. It also gives me an opportunity to continue developing knowledge on human biology and disease. I want to convert all of the data in the Protein Atlas Project into knowledge."

Wants to investigate what distinguishes healthy from sick

Through his large mappings, Mathias Uhlén hopes, however, to be able to find proteins that are both disease-specific and organ-specific.

Besides preparing a list of ingredients for different important organs, he wants to develop a list of ingredients for different diseases.

“For example, I want to understand how a kidney works both under normal conditions and when diseases occur. All medicines are targeted at proteins in the body. Understanding what proteins are involved in disease means understanding medicine development in the future,” says Mathias Uhlén.

Another future goal is finding proteins that can indicate that a disease is on the way of developing.

“My dream is that we will be able to take a blood sample once a year and, using it, discover a disease far before it breaks out. There are many diseases that could be good to discover before the symptoms present themselves. If, for instance, you find certain cancer forms early, you have a 90% chance of survival. If you find them late, you have a 10% chance. So by diagnosing the diseases in an earlier stage, you can go from 10% survival to 90%, without needing to develop any new medicines,” says Mathias Uhlén.

Research is the best there is

Alongside of his professorship at KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Mathias Uhlén has a 20%-professorship at the Technical University of Denmark in Copenhagen. In addition, he leads the work at the newly built Science for Life Laboratory in Solna. The large round building has been filled by 350 researchers and now an equally large building is ready to be filled by an equal number of researchers. This takes a great deal of time.

“But being named a Wallenberg Scholar makes it possible for me to continue doing what I love. The older I get, the fonder I am of the research process,” says Mathias Uhlén.

Text Ann Fernholm

Translation Semnatix

Photo Magnus Bergström