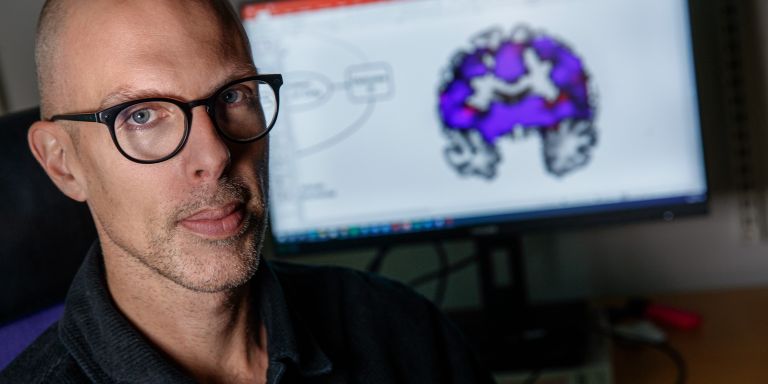

As a psychologist, Björn Lindström is interested in human behavior. Now he wants to map the mechanisms in the brain that enable us to learn from each other. Research into social learning can provide essential knowledge about how human culture is formed, including problematic phenomena such as conspiracy theories and extremism.

Björn Lindström

PhD, psychology

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2021

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Research field:

Understanding the psychological, computational and neural mechanisms involved in social learning – the process by which we acquire knowledge from and about other people.

Social learning is one of the key elements shaping human culture. But we still know little about the deeper mechanisms underlying social learning. What really happens in the brain when we learn from others?

As a Wallenberg Academy Fellow, Lindström is examining the neurobiological och psychological threads that intertwine to enable humans to learn from each other.

“Cultural evolution is essential to us as a species, and social learning is one of the psychological processes that enable this.”

Ideas and behaviors are transferred from one person to another, and also between generations. Contemporary technology is a consequence of gradual improvements over thousands of years.

“We learn from our parents and we imitate others who appear to be competent and successful. And we can do it much better than any other species,” says Lindström.

Developing a model

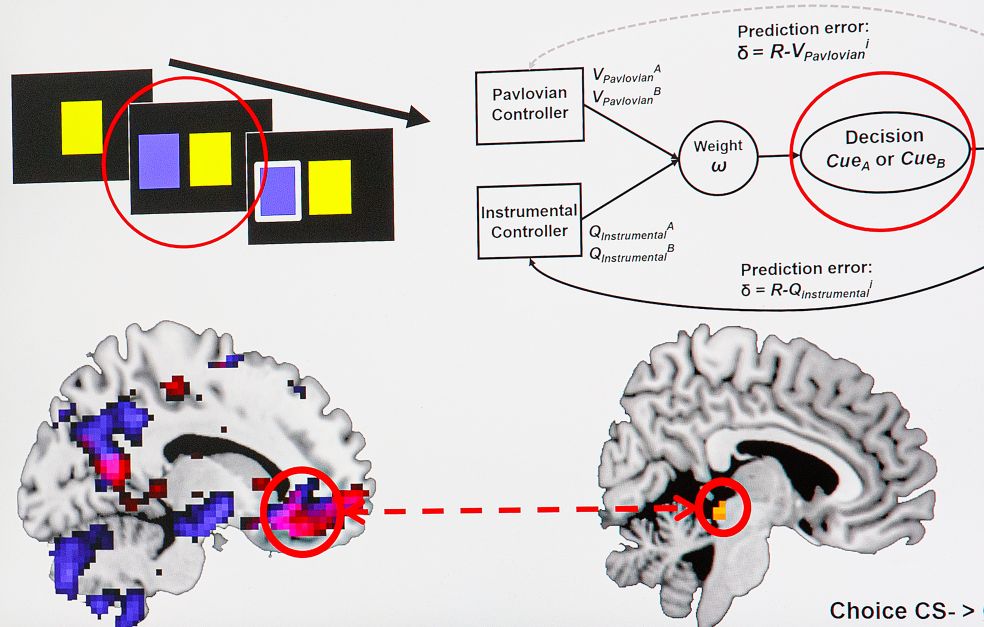

As part of his research, Lindström is delving into the mechanisms underlying social learning. In his search for answers, he is using a variety of tools, including behavioral experiments, mathematical models and brain imaging studies.

The aim is to identify the mechanisms for social learning, and to use this knowledge to create a model capable of explaining how individual learning mechanisms in the brain can express themselves as cultural patterns and behaviors.

“A mechanical model of this kind can help us to understand how human culture is shaped. Hopefully, in the future we’ll be able to use the model to describe differences in social learning between different groups of people.”

The findings may also provide new insights into autism, for instance, which can impact social learning.

Simulating social media

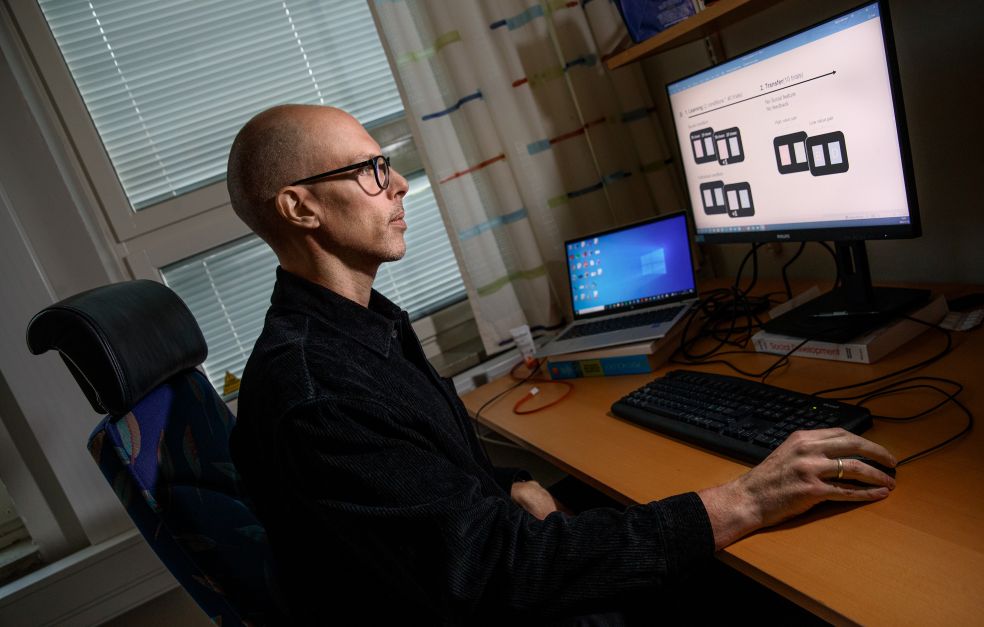

The research is divided into a number of sub-studies. Among other things, software resembling a simplified internet social media platform is being used to examine behavior. The researchers are using a simulated network that allows controlled studies. Subjects take part in an experiment involving a series of decisions at the computer.

“We want to see how participants learn via rewards and penalties. They are given access to certain social information and can see how others have reacted, or the decisions that have yielded most rewards for others.

Learning of this kind is also known as “reinforcement learning” and shows how people often adapt or change their behavior in line with reactions around them. For example, we are keen to post images or clips that attract large numbers of “likes.”

“Our hypothesis is that social learning is based on reinforcement learning,” says Lindström.

The next step is to analyze how participants behave; the researchers are attempting to describe their behavior mathematically. The mathematical model can then be related to real-life biology by way of brain imaging studies. These will enable the researchers to develop a model for understanding social learning on a large scale. To this end, part of the project involves computer simulation.

fMRI (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) is being used to study brain activity. A large number of brain images are collected during the tests. The images reveal the parts of the brain where most activity occurs while participants are performing their tasks.

“It seems the brain does in fact correspond to the signals predicted by our mathematical model,” says Lindström.

Combating conspiracies

But our ability to imitate others also has a downside, and can give rise to problematic phenomena. One topical example is the growing spread of conspiracy theories on the internet.

“Another is vaccine skepticism, which came to the fore during Covid,” Lindström says.

One aim of the research is to gain a better understanding of social learning processes of this kind, which have potentially negative implications for society.

“We need to improve our in-depth understanding. In addition to fundamental neurobiological knowledge, we’ll obtain some clues about how to combat the spread of conspiracy theories and extremism via the internet.”

The insights gained from the research could be applied to commercial social platforms, always assuming that businesses and society at large want to make use of the findings.

We learn from our parents and we imitate others who appear to be competent and successful. And we can do it much better than any other species.

The Wallenberg Academy Fellow grant has enabled Lindström to establish his own research team. After some years in Switzerland and the Netherlands, he has returned to Karolinska Institutet, where he received his PhD in 2014.

“Karolinska is an international research environment, and thanks to the Wallenberg Academy Fellow scheme, I can adopt a long-term approach to addressing challenging research issues. This would not be possible if I had to keep chasing funding,” Lindström explains.

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström