Project Grant 2017

Mast cells and their proteases: future targets for asthma therapy and diagnosis

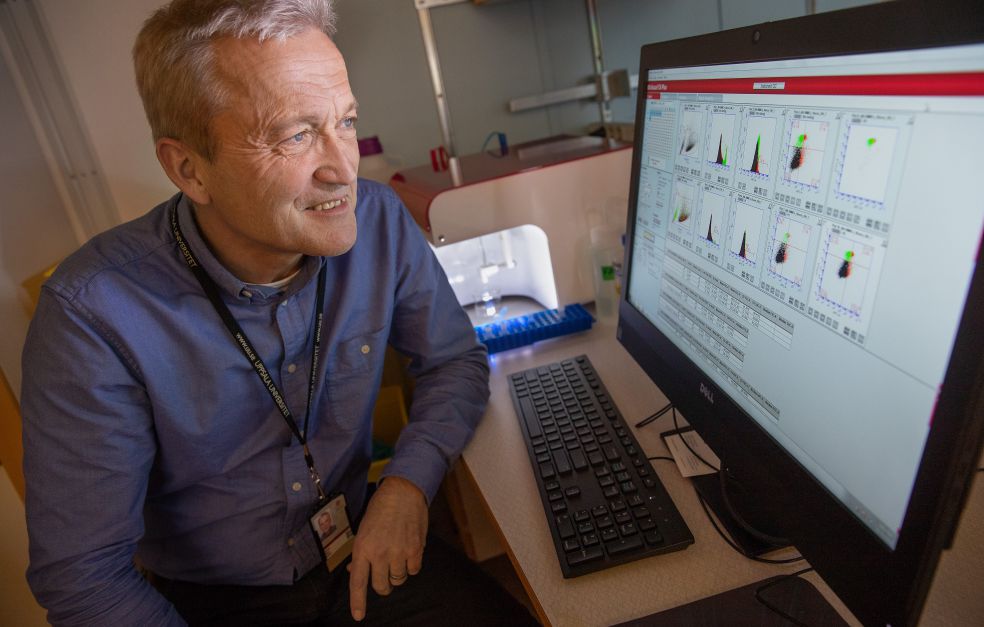

Principal investigator:

Professor Gunnar Pejler

Co-investigators:

Uppsala University

Mohammad Alimohammadi

Kjell Alving

Jenny Hallgren

Lars Hellman

Christer Janson

Andrei Malinovschi

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences

Sara Wernersson

Institution:

Uppsala University

Grant in SEK:

SEK 34,300,000 over five years

Asthma, a chronic lung disease, has become more common in recent decades. Some ten percent of adults in Sweden are affected. For children, the figure is somewhere between five and ten percent. The severity of the disease and its symptoms vary: from increased mucus production in the respiratory tract to severe attacks, with chest tightness, pain and severe breathing difficulties.

With treatment, many asthma sufferers can lead active lives without too much discomfort; others experience a marked deterioration in their quality of life. This is partly due to shortcomings in diagnosis and treatment of asthma, and a lack of methods for distinguishing between its different forms.

Professor Pejler thinks that a new approach is needed. He works at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Microbiology at Uppsala University. He heads a network of Uppsala researchers taking part in a research project funded by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

Focus on mast cells

The researchers are seeking clues in the body’s own immune system. The aim is to gain a clearer picture of the course of the disease at molecular level. The project is focusing on mast cells, a type of white blood cell in the immune system.

“Our overall vision is to understand the role played by mast cells in asthma. We want to know exactly what part they play in the disease, and which molecular mechanisms operate.”

Mast cells have a long evolutionary history, and are linked to the congenital immune system. They probably fulfilled an important function in early human evolution. One indication of this is that mast cells have the ability to neutralize toxins, such as snake venom.

“We no longer need as much protection against poisonous snakes, but historically it was probably a valuable characteristic,” Pejler says.

Harming and protecting

For many years mast cells attracted only desultory interest in the academic world, but recently the field has seen a huge upswing. It transpires that mast cells perform numerous important tasks. Studies have established that they are involved in allergic reactions and asthma, as well as a number of other diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, and certain forms of cancer.

“One unusual property of mast cells is that they can both harm and protect: they can trigger inflammations and allergic attacks, but also protect against infections of various kinds.”

The variability of mast cells renders the research field exciting and fruitful, although it is also difficult to put all the pieces of the puzzle together. This is why the project involves such a large number of prominent mast cell researchers from different disciplines, who will be contributing their perspectives and methods.

“It’s a great strength that the Wallenberg Foundation funding has enabled us to gather world-leading expertise along the whole chain, from basic science to clinical research.”

Secretions impacting asthma

When mast cells are active, they secrete large quantities of various inflammatory substances. One example is histamine, which makes the mucus membranes swell up and the bronchi contract. Research to date has focused on developing antihistamines, which inhibit histamine production.

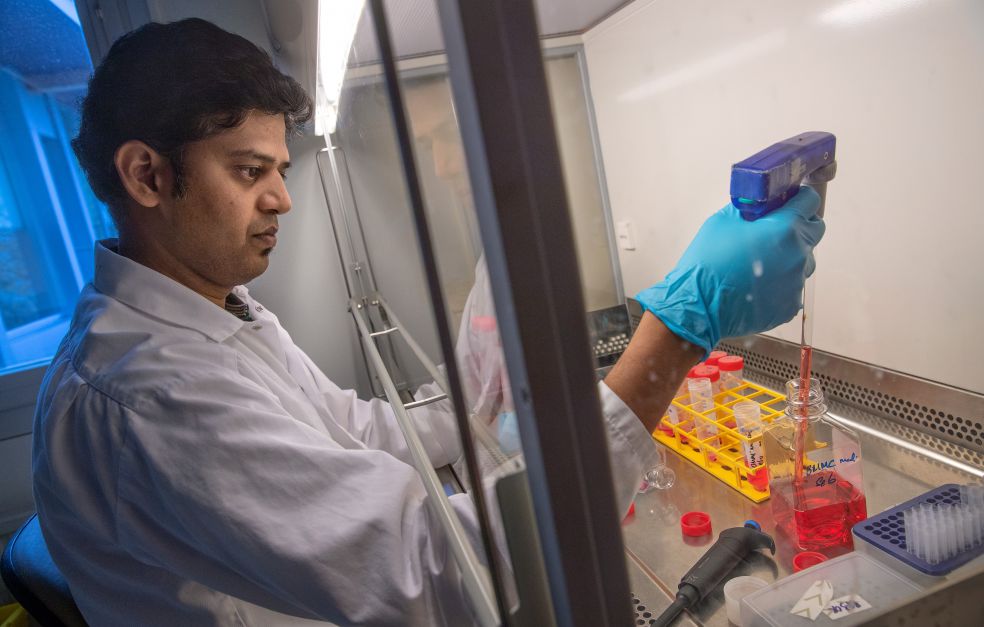

But mast cells produce other substances as well, including a type of enzyme called proteases. The researchers suspect that proteases play a major part in the way asthma manifests itself. Specialized animal models are being used to study what happens in the absence of mast cells or certain proteases.

“We can already see that mice that are missing one of the proteases – tryptase – experience milder asthma symptoms. We want to continue these studies to see whether there is a potential therapy using a drug that inhibits tryptase production.”

It has also been found that other proteases seem to have the opposite effect, i.e. a protective function. Mice lacking the enzyme chymase suffer a worse asthmatic reaction than those with this enzyme. These conclusions are supported by the outcome of clinical studies showing a correlation between chymase and better lung function in humans.

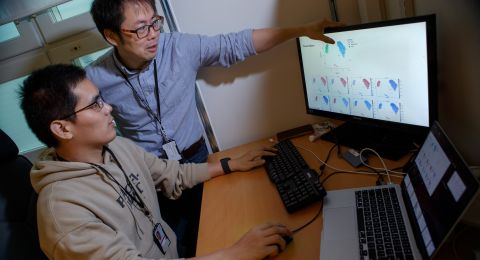

New findings yield better diagnosis

The researchers will be going on to analyze biobank material and samples from patients who have developed asthma. The results will establish whether a correlation can be seen between asthmatic reactions and activation of mast cells – and whether the level of different proteases differs between different forms of asthma. This would open the way for a completely new kind of diagnostics.

“We hope to be able to use the proteases as a new biomarker in asthma diagnostics,” Pejler says.

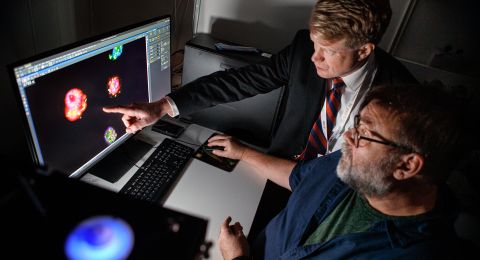

The road to new asthma therapies is much longer. The main priority is to gain a better understanding of the role played by mast cells and proteases in asthma. Among other things, the researchers want to study whether the genetic programming of mast cells differs between asthma sufferers and healthy individuals, and whether proteases in the mast cell are capable of influencing the genetic programming of other bronchial cells.

“We want to delve deeper into these mechanisms and find out exactly what happens when mast cells are spurred into action. We know that different proteases can have differing impacts, including how they affect cells in the lung. There are many unique discoveries we can build on thanks to the grant.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström