Project Grants 2011

The mucus layer and microbiota

Principal investigator:

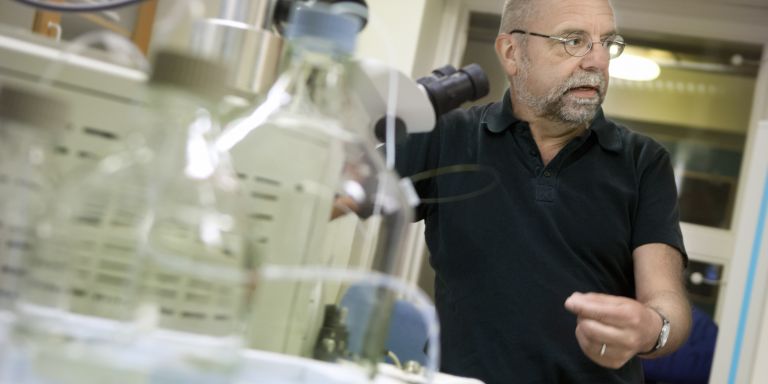

Gunnar C. Hansson, professor in Medical Biochemistry

Co-investigators:

Fredrik Bäckhed

Niclas G. Karlsson

Sara Lindén

Magnus Simrén

Susann Teneberg

Institution:

University of Gothenburg

Grant in SEK:

28.2 million over five years

We carry around about two kilos of bacteria in our large intestine. It’s not difficult to understand what a huge impact they can have on our health and diseases. Bit by bit we are gaining a better understanding of how intestinal bacteria live and are selected, and it’s a research team at the University of Gothenburg that has taken the international lead in the field. The reason we don’t get sick more often, despite this considerable quantity of bacteria, is that we have a protective barrier in our intestine, a major discovery that was made by Professor Gunnar C. Hansson and his colleagues.

“You can compare this with our skin, which is protected by several layers of dead cells . In the large intestine we have double layers of protective mucus instead, which is built up around the protein and mucin MUC2. Nobody noticed this before because mucus is invisible and contains lots of water. It’s similar to tears,” says Gunnar C. Hansson.

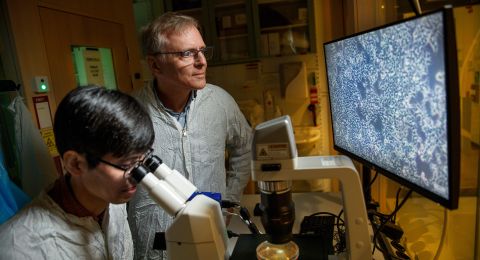

The inner of the two mucus layers keeps the bacteria in the intestine from getting down to the cells. It used to be thought that the immune system was designed to be able to differentiate between good and bad bacteria, but all these bacteria mainly live entirely separated from us. Another interesting find is that the intestinal flora is similar in different people and that we have a nearly identical carbohydrate clothing of the mucins that make a large portion of the mucus. There seems to be an as yet unexplained mechanism that has the ability to select bacteria, which may be because the bacteria can bind to these carbohydrate structures.

Mucus layer can break down

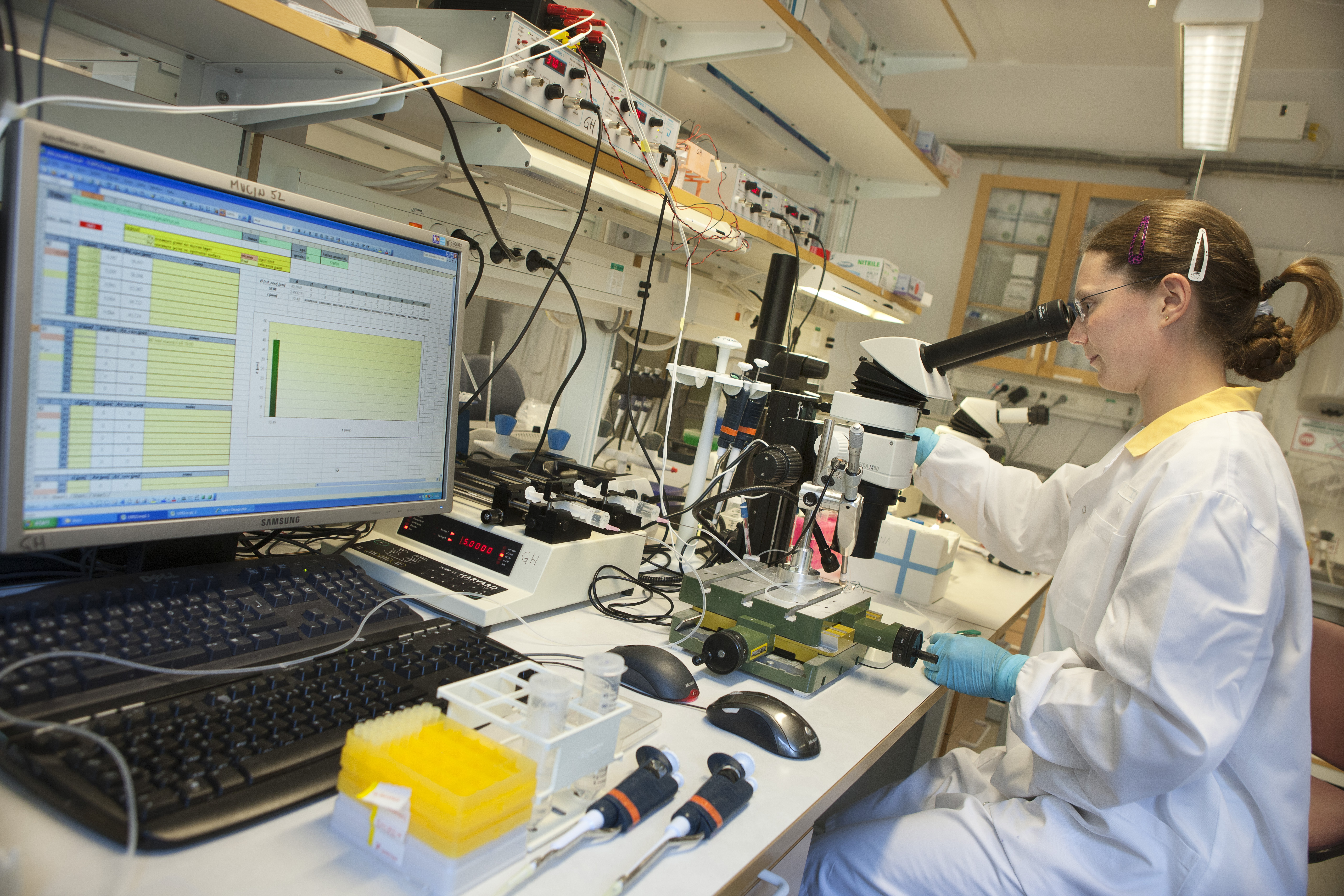

In a new project, funded by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, these researchers now want to enhance our knowledge of the outer mucus layer in order to understand the mechanism for how bacteria are selected, how they live in the outer mucus layer, and how they can break down the mucus to get energy for themselves. Among other things, the scientists will be creating an experimental animal model in which they will study the bacteria flora and human large-intestinal mucus.

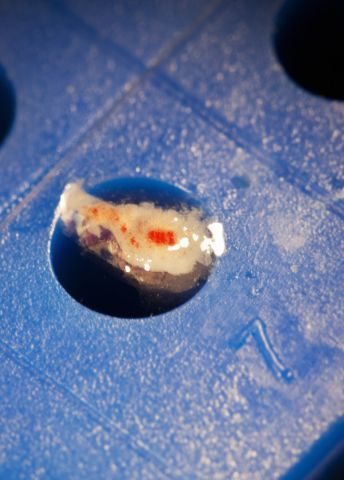

The mucus is formed in special cells, and the mucus molecules themselves are very densely packed inside them. When released, the mucus molecules expand more than a thousand times in volume. This unpacking can be likened to opening an umbrella, and the molecules arrange themselves in net-like structures that lie on top of each other, creating a protective filter that bacteria can’t penetrate.

“But in connection with the conversion of the inner mucus layer into the outer, the mucus expands. The holes get larger, and bacteria can penetrate and live in it, and at the same time they can eat it There’s a constant renewal process going on that takes only one or two hours,” Gunnar C. Hansson explains.

The whole point of the bacteria eating the mucus—this degradation—is that the body regains some of the energy that is used when the mucus is constantly renewed. Without bacteria humans would have to eat more. Through bacteria energy is returned to help supply the intestine’s cells, thus conserving energy for the body.

But bacteria can also bring about more rapid degradation of the mucus, destroying it. This can lead to various intestinal disorders, probably including ulcerative colitis, for one.

Transplanting bacteria

If they manage to gain a better understanding of which bacteria are healthful and how they are selected, scientists may be able to manipulate and transplant intestinal flora in patients. It could involve a new method for curing type-2 diabetes, for example, and Fredrik Bäckhed’s research team, which is included in the project, has also found a link to obesity. Obese individuals have a different mix of intestinal flora, with about one fifth of the bacteria deviating from normal.

“This research is still in its infancy, but the findings may ultimately help us understand and treat several major public health disorders,” says Gunnar C. Hansson.

Mucin research has also indirectly yielded new knowledge about cystic fibrosis. This is a disease where mucus blocks various organs and gets stuck in the lungs, causing severe lung infections. Mucus production occurs in the same way in the lungs as in the intestine, sparking hope that it will be possible to help patients by testing ways to produce more normal mucus.

More healthful foods

Another vision is to develop smarter foods by adding more healthful bacteria. Today’s healthful yogurts and similar products could be replaced by an entirely new generation of functional foods.

“You can imagine giving babies a bacteria shower at birth, but also producing scientifically developed foods, where we truly understand the role of bacteriaand can get the useful bacteria to stick and survive longer in the intestines.”

When Gunnar C. Hansson began to be interested in mucin in the late 1980s, he was the laughing stock of the research community. Few colleagues understood how anyone could be interested in mucus.

“People sometime called me ‘Mucus Hansson,’ and virtually no one was interested. But nobody’s laughing now. That’s the great challenge of basic research. You have to be prepared to probe the unknown, to be curious, and, above all, be persistent.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Donald S. MacQueen

Photo Magnus Bergström