Project Grant 2019

Breaking barriers to efficient immunotherapy of brain tumors

Principal investigator:

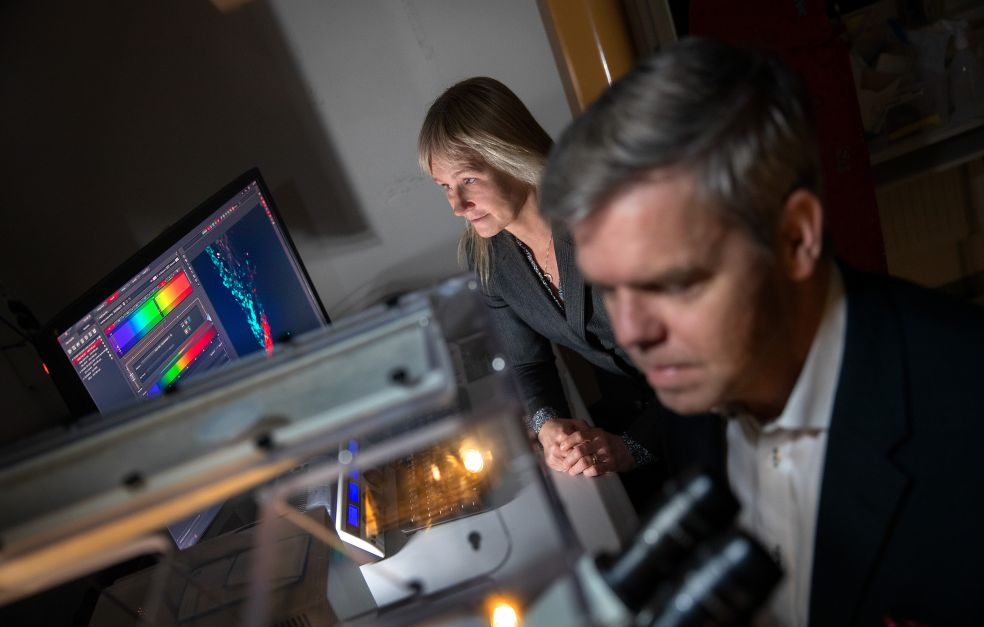

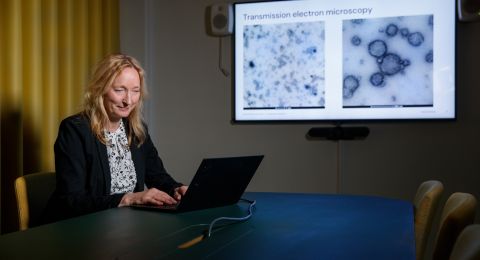

Anna Dimberg, Associate Professor

Co-investigators:

Uppsala University

Elisabetta Dejana

Magnus Essand

Bengt Westermark

Institution:

Uppsala University

Grant in SEK:

SEK 31,500,000 over five years

Every year about 1,300 Swedish people receive what many believe to be a death sentence: they are diagnosed with a brain tumor. Not all brain tumors are life-threatening, but many of them require complicated treatment with an uncertain outcome. And there is no cure at all for certain kinds of brain tumors. One example is the aggressive form known as glioblastoma. This cannot be removed entirely by surgical means; remnants of the tumor remain in the brain. Researchers Anna Dimberg and Magnus Essand at Uppsala University therefore believe a new, radical approach is needed.

“A powerful driver of our research is the prospect of being able to save patients for whom no effective treatment is currently available,” Dimberg says.

They are leading a five-year interdisciplinary project funded by Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. Their sights are set on developing new treatment strategies by using the body’s own immune system – immunotherapy. Cancer immunotherapy has had a major impact over the past few years, and immune checkpoint inhibitors was rewarded with the Nobel Prize in 2018. Immunotherapy is already used successfully to treat melanoma, lung cancer and some forms of leukemia.

New portals to the brain’s immune system

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are antibodies that inhibit the brake of T-cell, a specific white blood cells able to recognize cancer cells, and thereby unleash an immune response to attack the cancer.

But attempts to use this kind of immunotherapy on brain tumors have so far failed. The reason is that there are hardly any T-cells at all inside the brain tumor of a patient with glioblastoma.

“This is partly because the immune system in the brain is discrete from the body’s other immune systems, and is designed differently,” Dimberg explains.

“The brain must protect itself. The blood–brain barrier protects the brain from harmful substances, and keeps most of the adaptive immune system, including T-cells, out. So we have to find other ways into the brain’s immune system. But this is a balancing act, since we don’t want to cause too strong a reaction,” says Essand.

Exciting breakthrough

T-cells do not normally enter the brain, and the few that actually manage to do so are lost in the unfamiliar surroundings. If the immune system is to be pushed into attacking and disabling cancer cells in the brain, the researchers must induce the right microenvironment around the brain tumor. They have managed to do so in animal models, and the results are encouraging.

“We are actually the first in the world to ensure that the right kind of immune structures can be formed in association with brain tumors – it’s an exciting breakthrough,” Dimberg enthuses.

Brain tumor boot camp

In order to create the right microenvironment, the researchers have developed a virus with a tropism for the central nervous system that carries the building material needed to build lymph node-like structures. Normally, T-cells are activated in lymph nodes in the rest of the body’s immune system. In the brain, however, there are no lymph vessels that can transport immune cells and tumor-derived proteins to the lymph nodes except for the meningeal lymphatics.

“The nearest lymph nodes are found deep in the neck, but by inducing lymph node-like structures, known as TLS (tertiary lymphoid structure), we create an environment in the brain in which T-cells can be trained up and learn to recognize the brain tumor,” Dimberg explains.

“You could say we place a field hospital – or a boot camp – inside the brain tumor,” Essand says.

One aspect of the research is to enhance the transport pathways into the brain, to make it easier for the T-cells to make their way from the bloodstream to the brain tumor.

High-risk idea with huge potential

The project has brought together specialists from a number of fields, including tumor immunologists, vascular biologists and virologists. One of the researchers is Bengt Westermark, doyen of the research world, and a leading international expert on glioblastoma.

“Thanks to the funding we have received from Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, we have the chance to perform absolutely the best type of analysis, and have no constraints on our methodology. We can also adopt a more long-term approach, and do not need to chase quick results – we can get to the heart of the matter instead,” says Dimberg.

“It’s an extraordinary privilege to be able to work in this way,” Essand adds.

The research concept is a radical one, since it involves a risk of triggering an immune reaction in the brain. But the idea rests on a solid foundation, and if lives are to be saved in the future, it is necessary to explore new, more daring treatment strategies.

“Many patients today have no curative treatment, which is why high-risk projects like this one are needed. We hope that when the project is finalized, we will have a method that can be tried out in clinical studies,” says Dimberg.

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström