Great strides are now being made in what we know about our sense of smell. The recently discovered ability to measure signals from the olfactory bulb in the brain opens the way for new methods of identifying diseases. Loss of smell is linked to diseases such as Parkinson’s, and this symptom could be used to make a diagnosis up to ten years earlier than at present.

Johan Lundström

Associate Professor of Experimental Psychology

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, prolongation grant 2018

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Research field:

Multisensory neuroscience, smell perception

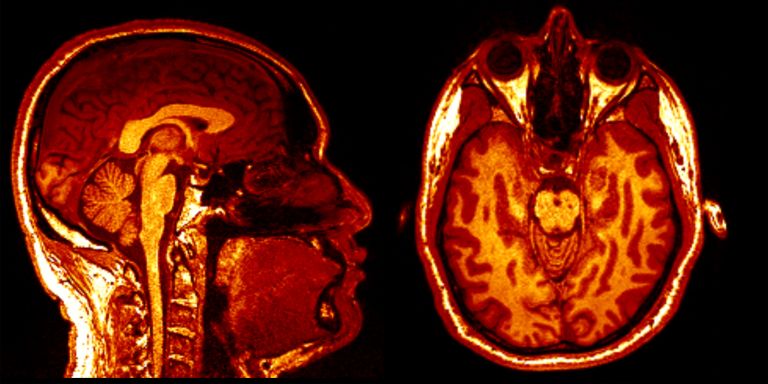

Johan Lundström is a researcher at Karolinska Institutet, and has for many years researched into our sense of smell. As a Wallenberg Academy Fellow he has been given the opportunity to pursue lines of research that have yielded fresh insights into how the sense of smell works. Among other things, the funding has made it possible to develop a method of exploring the olfactory bulb, the first station in the brain where odors are processed.

“We use standard EEG to examine activity in the brain’s neurons, albeit in a new way so we can delve deeper into the brain. For the first time we’ve been able to detect signals from the olfactory bulb.”

This method enables scientists to ascertain how our sense of smell normally works, but it can also be used to indicate diseases. Parkinson’s is one disease linked to an impaired sense of smell. It is often described as a motor disease, but the most common early symptom is a deteriorating sense of smell.

“We see that the disease begins in the olfactory bulb, and can measure a marked decline in sense of smell as much as eight to ten years before the patient receives a clinical diagnosis. So the disease could be detected much earlier than is currently the case,” Lundström says.

The method could be used as a simple test to measure olfactory bulb function, e.g. as part of an annual health check-up. This would make it possible to identify people at risk of developing Parkinson’s.

“The test can show whether an in-depth examination should be carried out, such as a DaT scan to measure dopamine deficiency. We have already shown scientifically that the method works, but we lack funding to develop a prototype.”

Lundström is now involved in multiple projects to see whether measuring olfactory function may be relevant in relation to other diseases, such as Alzheimer’s.

One of nature’s best signal systems

Humans use smell and taste to explore their surroundings. Our sense of smell evolved to help us detect danger, such as poisonous foods or an approaching fire.

“All organisms alive today are able to detect chemicals. It’s one of the best signal systems nature has come up with. Odors can travel long distances night or day, and can linger for a long time. It’s an optimal signal source,” Lundström explains.

But there are also people born without a sense of smell. Lundström’s research has shown that they compensate for this by relying more on their sight and hearing.

“The unique quality of being a Wallenberg Academy Fellow is the freedom I have as a researcher to take risks. I have the time and the resources to explore the most promising and interesting issues, even where it is not certain that the outcome will be optimal. The support we have received has led to a breakthrough that we can now develop further.”

Other studies include patients who temporarily lose their sense of smell. Nasal polyps are growths on the mucosa in the nose, and affect about three percent of the population. The problem can be remedied with a simple operation, but the patient’s sense of smell is usually not fully restored. The reason is that while the olfactory region in the brain is inactive, other senses take the opportunity to move in.

“The brain can be likened to a fancy penthouse suite. It’s not usually empty for long; there’s always a line of would-be occupants. If we lose input in one region of the brain, there are immediately numerous other inputs knocking on the door, wanting to move in.”

Covid-19 and loss of smell

Loss of smell also affects many people who contract the SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus. Lundström has reoriented his research as a result of the pandemic. Studies have shown that at least half of people confirmed positive for Covid-19 suffer loss of smell. An estimation is that at least ten percent of those people will lose their sense of smell long-term. A conservative estimate is that by spring 2021 at least 30,000 people in Sweden had experienced total loss of smell.

“We’re trying to work out what part of the sense of smell the coronavirus affects, but we’re also keen to study how smell training can help people to regain their sense of smell.”

One theory is that the virus attacks support cells in the olfactory mucosa. These cells are needed for the odor receptors to be able to process odors. If the odor receptors do not receive the support they need, the sense of smell will be lost. Another theory is that the virus attacks the olfactory bulb. It is now hoped that the recent new findings about the olfactory bulb can form the basis for a new type of electrical treatment.

“The idea is to kick-start activity in the olfactory bulb by stimulating nerves in the skin that lead all the way into the olfactory bulb. Our tests reveal that the olfactory bulb responds better to odors, and that the sense of smell improves.”

Some Covid-19 patients have also suffered from parosmia – dysfunctional smell processing causing pleasant smells to be perceived as unpleasant.

“Losing one’s sense of smell is horrible – not being able to enjoy food or the scent of one’s partner or children. But parosmia is actually even worse,” says Lundström.

The research shows that most patients are helped by smell training, a method that also reduces the risk of the problem becoming permanent.

“My advice to anyone who loses their sense of smell is to start smell training. The earlier you start, the better the effect. We have set up two websites – lukttest.se in collaboration with fellow researchers in Israel, and lukttraning.se. We hope to see a smell clinic open in Sweden at some point in the future, because the Swedish health care system lacks knowledge about our sense of smell.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Jonas Borg