Project Grant 2020

Adipose tissue senescence and metabolic disease in man

Principal investigator:

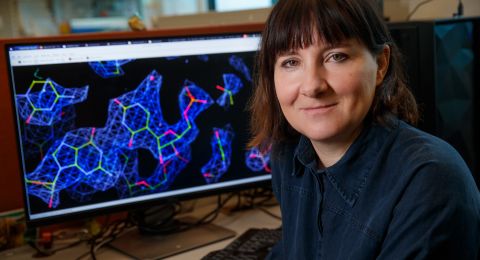

Dr. Kirsty Spalding

Co-investigators:

Uppsala University

Göran Possnert

University of Gothenburg

Ulf Smith

Institution:

Karolinska Institutet

Grant in SEK:

SEK 31 million over five years

Obesity is a ticking global health time-bomb. Over the past 40 years it has become ten times more common in children and young people around the world. It causes growing health problems such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer.

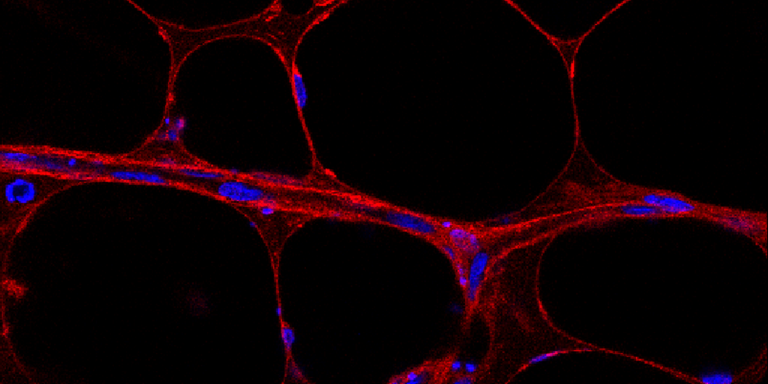

The unfavorable obesity trend has sparked a growing interest among researchers in the body’s fat cells. Fat cells were considered simple cells whose main function was to store and release energy. They had a fairly low profile in a population in which most people were of normal weight. But it is now clear that fat cells are involved in many bodily processes. Kirsty Spalding elaborates:

“We’re beginning to appreciate that fat cells have many different functions, impacting many different aspects of human health, extending, for example, from reproduction to the immune system, cancer and, not least, metabolic health.”

Spalding is a researcher at the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology at Karolinska Institutet (KI), and is heading a project aimed at examining a specific mechanism: how premature cell ageing in adipose tissue can be linked to type 2 diabetes and other metabolic diseases.

The project is a collaboration between researchers from KI, the University of Gothenburg and Uppsala University, and is being funded by Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

“We complement each other well, and anticipate major synergies. Thanks to the size of the grant, we also have a real chance of developing a field that hold lots of potential and is rapidly expanding.”

Cells ageing before their time

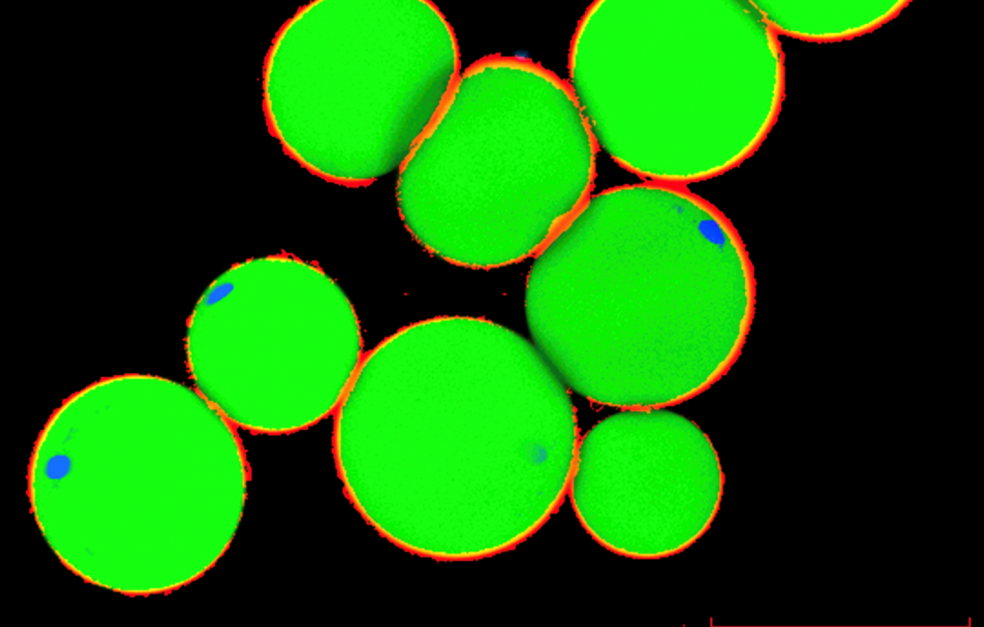

The researchers are interested in a condition that in scientific terms is known as senescence. It is defined as a state of irreversible cell cycle arrest. Senescence can occur as a normal part of aging, or in some cases due to cellular stressors, for example DNA damage, resulting in a state celled premature cellular senescence.

“When I first heard about senescence, I had the impression that these cells were old and inactive. But nothing could be farther from the truth. It’s a mistake to think they are completely passive, just waiting to die,” Spalding says.

Senescent cells secrete inflammatory substances that can impact neighboring cells or whole tissue. Harmful cells accumulate over time, potentially causing systemic inflammation. This may in turn cause cancer and compromise the function of entire organs.

Senescence occurs in different parts of the body, but this project is focusing on adipose tissue. The researchers have observed an increase in prematurely ageing cells in the adipose tissue of people with diabetes. Now they want to find out more about the causes.

“We are interested in investigating the mechanisms whereby senescence is induced, including what triggers senescence and which cell signaling pathways may be involved.”

Knowledge about these signaling pathways may eventually enable researchers to block them, thereby preventing cells from exiting into a senescent state.

New diagnostic potential

The project also includes a study of the substances secreted by the senescent cells. The scientists want to know more about how these molecules cause changes in the body, such as impaired glucose tolerance and insulin resistance, which can lead to diabetes.

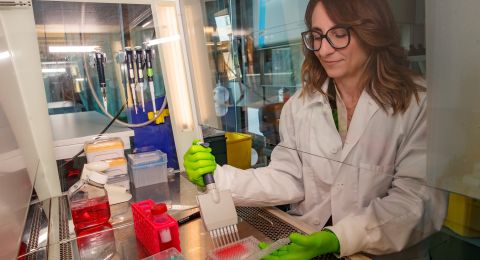

This information will in turn offer scope for new ways of identifying people at risk of developing diseases. The researchers have access to a large patient database, and will be matching the secreted molecules with blood samples from people in various stages of disease.

“We hope to develop a new diagnostic test for diabetes and other metabolic diseases.”

Unexpected help from the Cold War

Spalding is isolating senescent cells and attempting to ascertain their age. She is using a method she herself developed during her time as a postdoctoral member of Professor Jonas Frisén’s research team.

“It’s a slightly wacky but super-effective method that enables us to determine the age of cells using radiocarbon dating.”

The method makes use of the numerous above ground nuclear weapons tests carried out in the

1950s and 60s, which more than doubled the level of radioactive carbon-14 in the atmosphere. Since then levels have gradually fallen. The scientists measure the amount of carbon-14 in the DNA of the cell, enabling them to determine with a high degree of accuracy when the cell was formed.

“The question is whether more senescent cells form as we grow older, or whether it is in fact the immune cells that become less efficient at getting rid of old senescent cells.”

As part of the project, it is also planned to carry out a pilot study to see whether it is possible to kill prematurely ageing cells using a new class of drugs called senolytics. Data on the effect of these drugs on age-related diseases in animal models are promising, and preliminary results from two tests on humans give cause for optimism.

“Clinical trials are expensive, and a long way off, but we want to conduct a pilot study to see how a pharmaceutical study involving people at risk of developing diabetes could be designed.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Martin Stenmark, Daniel Roos, Spalding research group