Wallenberg Scholar Marianne Gullberg explores the relationship between language, thought and brain in language learning and multilingualism. She also highlights the importance of gestures. The results can be used to develop new virtual tools to improve language learning.

Marianne Gullberg

Professor of Psycholinguistics

Wallenberg Scholar

Grant from Marcus and Amalia Wallenberg Foundation

Institution:

Lund University

Research field:

Adult second language learning and multilingualism, both in speech and gestures; language processing, including neurological aspects.

In her youth, Gullberg spent time abroad, learning new languages and experiencing different cultures. When she returned to Sweden to study general linguistics, she was struck by the huge difference between theory and practice.

“There was such a marked discrepancy between the situation when you sit in a classroom to learn a language and what happens when you travel to the country where the language is spoken, where you are bombarded with quick-fire communication and have no time for reflection.”

Linguistics was dominated by structural topics and theoretical frameworks, but Gullberg found that research was lacking on how language is actually used in real time, particularly when the language is new to the user.

The art of learning a new language

Her curiosity led her to a career in research. For ten years she was a research leader at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in the Netherlands. In 2010 she was recruited by Lund University to two positions: Professor of Psycholinguistics and Director of the Humanities Lab.

She has addressed big issues, such as what really happens when we learn a new language, and how different languages interact with each other in a multilingual person. Human language is a complex communication system, linking cognition, emotions, memory and brain activity.

“It’s an incredibly rapid process – a question of milliseconds. In that space of time we manage to go from a vague idea about what we’re going to say to choosing the right words, grammar, sounds, intonation and gestures. The converse – understanding what someone else is saying – is equally rapid and complex. How do we manage it when we learn a new language, or when we have to cope with more than one language at the same time?”

Myths about gestures

Part of Gullberg’s research addresses the interplay between speech and gestures. There are plenty of preconceived ideas about how gestures are used in different languages. Italians, for example, are often considered to be highly expressive.

“People like to imagine a street corner in Naples, where elderly Italian men stand around gesticulating wildly. But seat them on opposite sides of a table top and the lively gestures disappear. Our research finds no support for the view that Italian or French people use more gestures than Swedes.

Gullberg likes to play myth-buster, although she is also careful to be nuanced. There are differences in gestures between languages, and we do tend to notice modes of expression that are unfamiliar to us. The French, for example, have a more extensive repertoire of gestures that can take the place of words.

“There are numerous conventional gestures that serve as standard expressions, such as thumbs up or tapping the nose with the index finger.”

“The Wallenberg Scholar scheme is a dream grant. It provides funding and time to take on risky projects and completely new topics. For me as a humanities scholar, it is an honor to receive a grant of this importance, which also creates new networks.”

Unconscious gestures part of the language

But to a linguist the gestures we produce unconsciously are more interesting. They are called “co-speech gestures” and form part of the linguistic system. When we are faced with another person, we include information from gestures and base our understanding on all aspects of communication.

“In fact it’s usually difficult to ignore gesture information – we register it automatically.”

Co-speech gestures are colored by each language. One example is the difference between Swedish and German. In German the verb is placed at the end of the clause, which means that a gesture made in the middle of a Swedish sentence comes at the end of a German one. These differences also offer scope for interesting experiments, such as how people react to foreign accents, for example.

“A foreign accent is not just a question of pronunciation – the hands play a part too. Can someone who speaks German or French with perfect pronunciation but gesticulates ‘in Swedish’ be perceived to have an accent?”

Virtual teachers

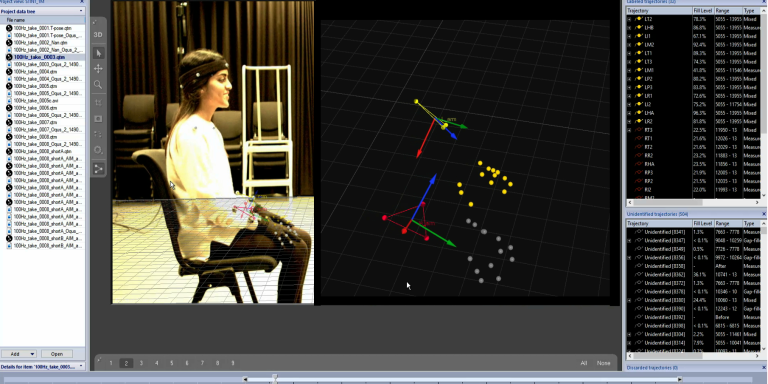

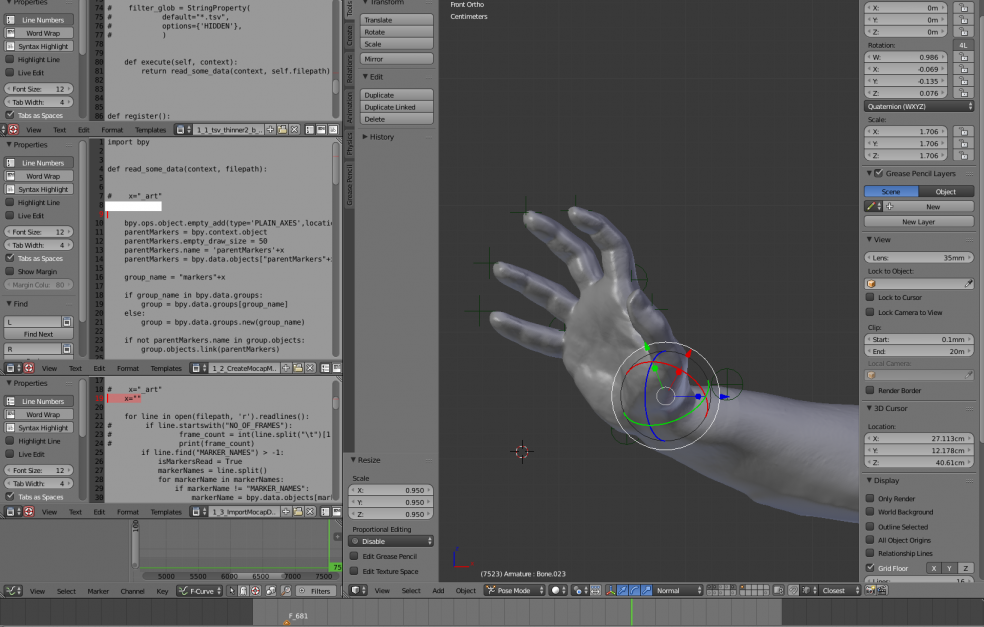

The research is being conducted experimentally, and combines methods traditional in the humanities with high-tech instruments. The researchers use articulography to measure tongue movements. Motion capture is a technique we have seen used in movies such as Avatar and Lord of the Rings. Tiny sensors are placed as markers on different parts of the body. A three-dimensional recording of the markers then allow us to map body movements. This method yields highly detailed information about the interplay between speech and gestures.

Another part of the project involves use of electroencephalography (EEG) to record how the brain reacts to language we are listening to.

“It gives us a fantastic opportunity to lift the lid and see what really happens in the brain, for instance if a gesture is made in the ‘wrong’ place”.

The project also uses the motion capture data recorded to build virtual language teachers capable of communicating both speech and gestures in a virtual environment.

“Language teaching can be supplemented by recreating a ‘virtual Frenchman’ to help Swedish students learn a foreign language, as well as new arrivals to learn Swedish. After all, language plays a central part in integration, and virtual training opens up new possibilities.”

Another application is the creation of social robots.

“Thanks to the virtual speakers now available we can help to make robots more ‘alive’ and realistic in their speech and gestures.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Caroline Larsson, Henrik Garde, Nadia Frantsen