Mia Liinason

Associate Professor of Gender Studies

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2015

Institution:

University of Gothenburg

Research field:

The fight for women’s and LGBT rights

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2015

Institution:

University of Gothenburg

Research field:

The fight for women’s and LGBT rights

We meet Mia Liinason at the University of Gothenburg, Department of Cultural Sciences, which, somewhat surprisingly, is housed in a Chalmers University of Technology building. She works there as a senior lecturer in gender studies. This is an interdisciplinary subject, and a young one at that. Only five years ago Liinason was awarded the very first doctorate in gender studies at Lund University. Her thesis addressed the emergence of the subject.

“It is fairly unusual to research a subject from within, so to speak. I might be sitting in a meeting when someone would suddenly exclaim ‘Hey, are you conducting a participant observation study now…?’ But I really enjoy researching in such a new field. It offers plenty of opportunity to be involved in shaping the subject,” Liinason says.

“It is wonderful to have been admitted as a Wallenberg Academy Fellow. It represents recognition of my work as a researcher, as well as of this somewhat contentious subject – a newcomer to the academic world. And the fact that the grant is generous and broadly framed means I will be able to carry out an open, exploratory project.”

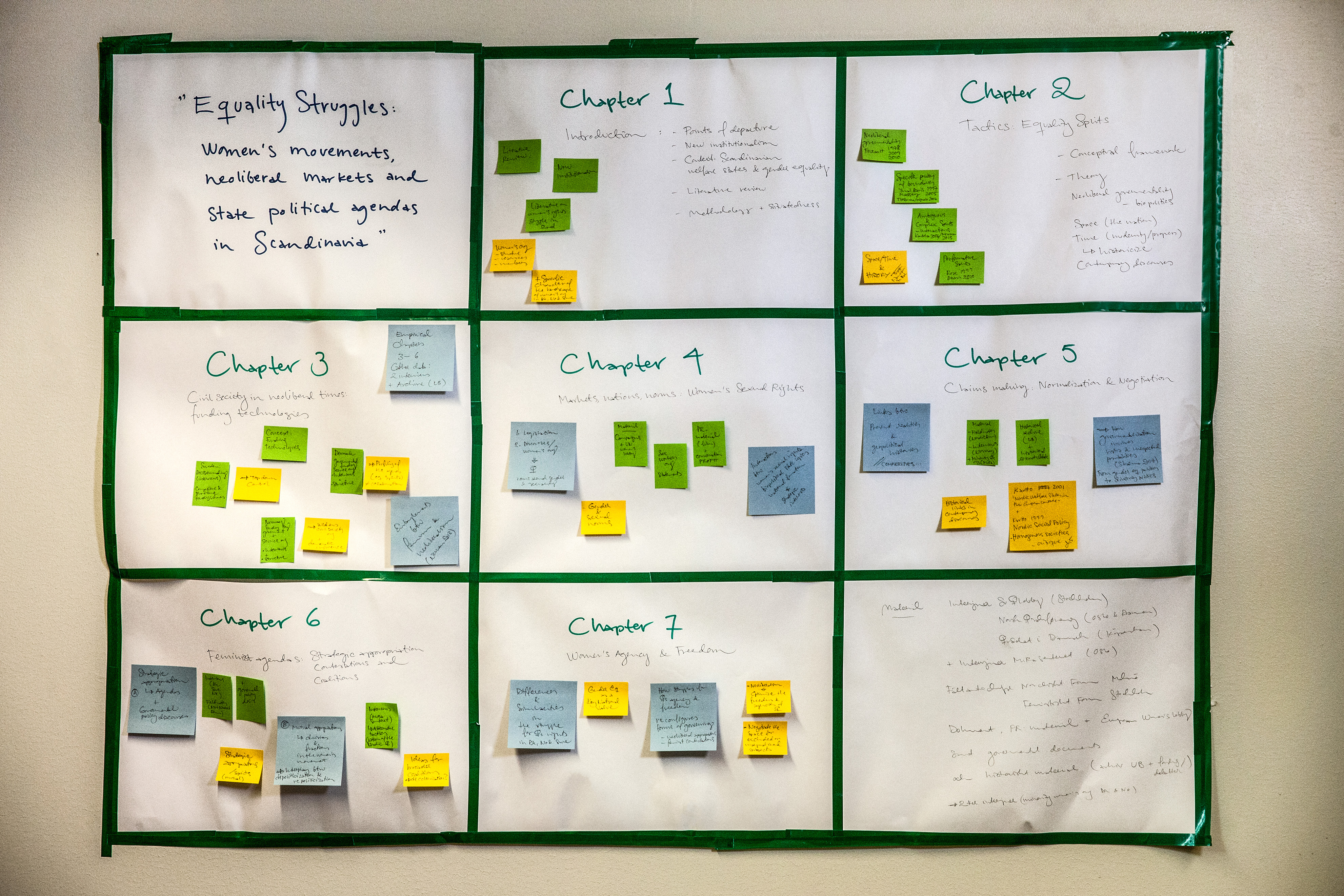

In recent years her research has largely focused on the struggle for women’s and LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transsexual) rights – how it differs from one place to another, and what happens when people from those places meet. As a Wallenberg Academy Fellow, Liinason will be studying and comparing the struggle for rights in Russia, Turkey, and Scandinavia.

Pride parades are attacked by the police in Turkey and banned by the courts in Russia, while in Scandinavia police, politicians and government agencies take part in the processions. But this has not always been to the liking of activists – not, for instance, when right-wing populist politicians take part, or the Migration Agency, which has been heavily criticized for putting LGBT people in danger by sending them to areas where they risk persecution.

“It is interesting that conflicts are so different. Women’s struggles has often centered on power and gender, but in our research we want to study ‘interacting power structures’: how nationalism, sexism, racism, homophobia and transphobia combine.”

Today, although there are substantial regional differences, the fight for the rights of LGBT people and women is an international movement. So Liinason and her colleagues will be studying cross-border co-operation, both on the spot in the three regions, and using the internet.

“Globalization has often been criticized for buttressing power centers throughout the world. But it has also given people the opportunity to meet across borders in their struggle for social rights. Additionally, I want to examine how the sense of belonging to a community can be created remotely, for example how solidarity can be expressed on social media.”

The political process known as neoliberalism is often subject to the same criticism as globalization. Simply put, neoliberalism means that the state is given less power and influence, but also less responsibility. Critics consider this increases the gap between the haves and have-nots in society. But Liinason points out that when the state wants to reduce its influence, more resources are often allocated to non-governmental organizations and bodies, e.g., women’s or LGBT rights groups, which are expected to assume greater responsibility for resolving their own issues. But they do not always use the resources in the way the state intended.

“Both globalization and neoliberalism impact the movements I am studying, but the movements are also involved in negotiating to achieve the society and the politics we want. So activists in turn impact globalization.”

Liinason is studying not only the battle, but also our perception of it.

“It’s often assumed the only way to conduct a fair fight is to join the modern, western, secular project. But there is more than one way to live a life in freedom. This is one of the reasons I have chosen to study Russia and Turkey in particular. They are so complex, historically speaking. For instance, during the Soviet era women were prominent in the labor market. And for many years Turkey had the stated aim of modernizing the country and making it more secular.”

In recent years there has been growing governmental oppression of dissidents in both Russia and Turkey. And the huge number of refugees from Syria has given Turkey a new role in Europe. As a researcher, Liinason must consider a number of dimensions – as project leader she must also think about security.

“Before we carry out fieldwork we have to see what the Ministry for Foreign Affairs says about traveling to these regions. A lot has changed since I began the project.”

Liinason herself is not politically active at present. She has no time, and it would be difficult to research a political movement to which she herself belonged. But in a sense her research was born of political commitment. Liinason was a cultural writer, and she noticed that she was drawn to issues of women’s and LGBT rights. She felt she needed to learn more, and decided on gender studies. Then she thought that her words as a writer would carry greater weight if she had a PhD. Once she had begun to do research she wanted to continue a little more, and a little more...

“Research is incredibly inspiring and rewarding; it enables me to get to the bottom of important and complex issues. But it doesn’t mean I won’t once again concentrate on writing at some point.”

Text Lisa Kirsebom

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström