Axel Englund’s research inhabits the border zone between literature and music. He now has a new project in which he is studying the relationship between music, corporeality and sexuality among modernist writers, including Proust, Mann and Musil. The aim is to provide a new understanding of music’s central role in the modern novel.

Axel Englund

Professor of Literature

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, prolongation grant 2019

Institution:

Stockholm University

Research field:

The role of music in literature, particularly from modernism onwards

Englund is a professor of literature, but also has a thorough grounding in music. After high school he studied theory of music and composition in Sweden and Germany.

“When I moved from the artistic to the academic world, my interests swapped places. My main focus became literature, although I kept one foot in the musical world.”

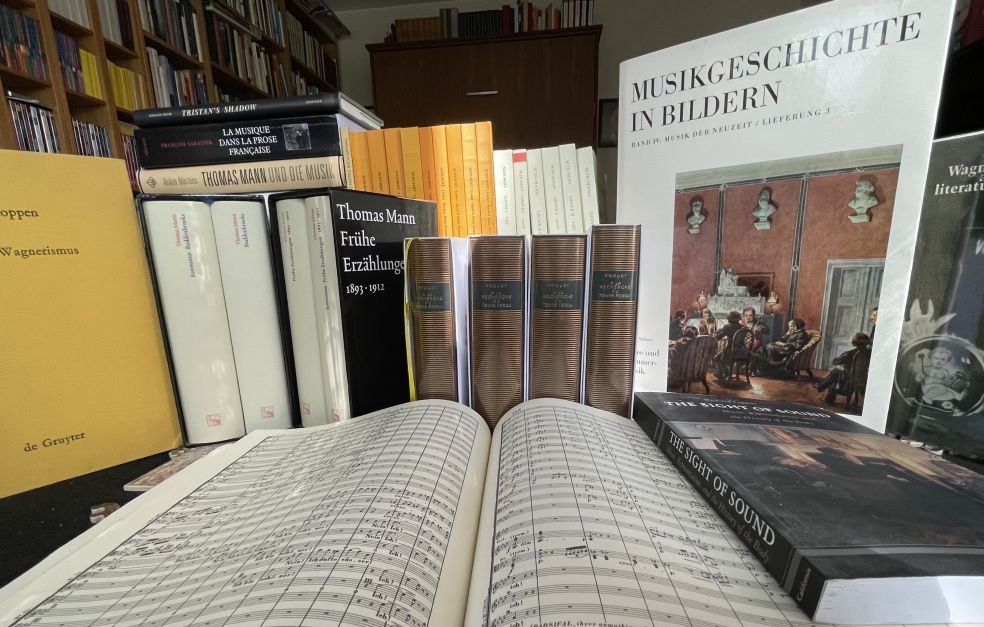

As a Wallenberg Academy Fellow, he is concentrating solely on relationships between word and note. In his book Mörkerstråk (“Strings of Darkness”) he discusses music in 19th century German poetry. Four poets are studied in depth: Rainer Maria Rilke, Nelly Sachs, Paul Celan and Ingeborg Bachmann.

Englund writes about the idealized role of music in German culture, and how its status changed due to the Second World War and the Holocaust. Playing Mozart did not serve as a vaccine against barbarism – a painful realization that changed the German self-image, and that can be traced in various ways in its poetry.

Another part of his research deals with opera in our own time, and has resulted in a book entitled Deviant Opera – Sex, Power, and Perversion on Stage.

“It’s an entirely different subject, which I gradually began to study due to my interest in poetry and music.”

Englund describes how contemporary directors take ever greater liberties with works, and become co-creators. Common ingredients are sexualized power, fetish aesthetics and sadomasochism. The aim often seems to be to put on innovative productions.

“But purportedly radical approaches turn out to include established conventions. For instance, operas are often set in mental hospitals, exploiting the operatic interest in tragedy, illness and hallucinatory borderline conditions. One aim of the book is to broaden the reader’s horizons and see what is being created on the opera stage today.”

“Thanks to the Wallenberg Academy Fellow scheme, I now have the time to read and think in peace, and have been able to pursue the lines of inquiry that are most intellectually fruitful. Most of all, I value the freedom. Research requires you to come up with new ideas. Many researchers today, however, are obliged to follow a predetermined plan, and are prevented from following up the most interesting insights.”

Disembodied music

In his next project Englund will be focusing on the role of music in the modern novel. The power of music over humankind is an ancient idea. Back in antiquity Plato believed that music strongly influenced the soul – but by the late nineteenth century ideas about music had assumed a new and very different nature.

“A radical change occurred in the way music is performed, first with the advent of the phonograph, then the gramophone and radio. For the first time in history music became disembodied – it could be heard without anyone’s hands or mouth being present in the room.”

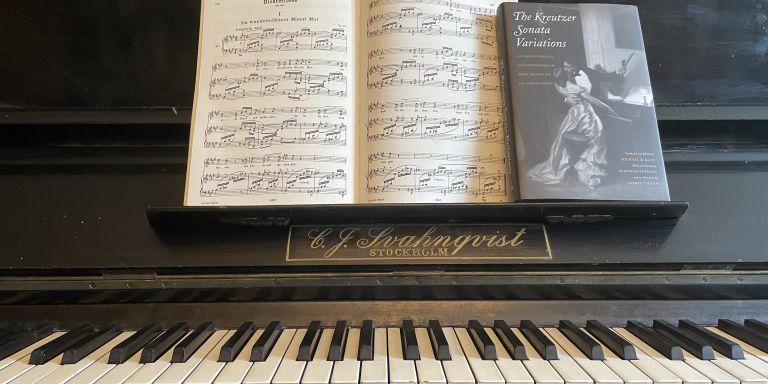

Bourgeois music culture, centered on the piano, now faced competition from new mechanical devices. Yet novelists of the time stressed that music was an embodied phenomenon. Only when it became possible to listen to music through a technological device, did it become relevant to speak of “live” music.

“What’s remarkable is that numerous authors with an abiding interest in both music and new technology nonetheless describe music primarily as an embodied, social phenomenon.”

One prominent example is Marcel Proust. His novel Remembrance of Things Past, published in seven volumes between 1913 and 1927, is chock-full of automobiles, aircraft, telephones and other modern inventions.

“Proust was also extremely interested in music. But over almost four thousand pages no mention is made of a single gramophone playing music; it is always performed live.”

Music and sexuality

The view of music was also influenced by ideas in the nascent field of sexual science. Music and musicality were linked to erotic desire and suppressed sexual identities.

“Many sexologists saw links between various sexual preferences, for example homosexuality, and musicality. And for Freud and psychoanalysis, musical performance represented an aesthetic sublimation of the libido.”

Music was also a burning topic in the discussion of gender roles. Some experts put forward theories on the harmful effects of music, particularly on women.

“There were doctors who thought that music affected reproduction, and claimed that women could not be piano tuners, because their menstrual cycle would be adversely affected by daily exposure to the sound of a piano.”

Englund is studying a broad selection of novels from the period 1900–1930. These include works by central modernists such as Thomas Mann, Robert Musil and James Joyce, as well as lesser-known names and early lesbian and gay literary classics.

He hopes the project will add to our understanding of the modern novel. Earlier research has mostly examined how authors have viewed music as an abstract structure, and have been inspired to experiment with narrative techniques. Some modernists wrote in fugue or sonata form, for example.

“But I want to present a different perspective by showing how the art of sound came to represent the physical, evocative and carnal in literature.”

Nowadays we live with constant access to music, not least via mobile streaming services. It is hard to imagine a time just over a hundred years ago when almost all music was “live”.

“It’s just as hard to conceive of a situation in which eroticism was so hidden compared with the present day, but the early twentieth century is an exciting era to explore. Therein lay the origins of what we have come to be.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Sören Andersson, Edith Askegård, Axel Englund, SVT