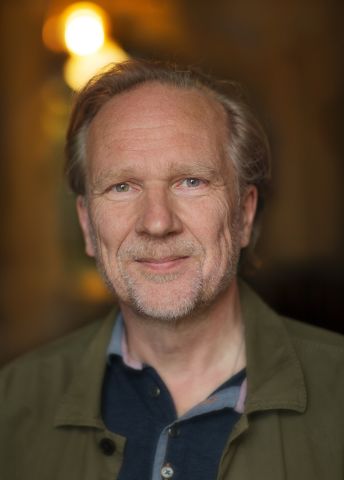

Tore Ellingsen

Professor of Economics

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Stockholm School of Economics

Research field:

Institutional economics, organizational economics, behavioral economics

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Stockholm School of Economics

Research field:

Institutional economics, organizational economics, behavioral economics

One might imagine that researchers in economics mainly concern themselves with studying economic policy, labor markets or the financial sector. But there is also research in the overlap between philosophy, psychology and economics. Ellingsen is a professor of economics at Stockholm School of Economics, with a particular interest in ethics.

That interest was born during his time as an undergraduate, when he discovered that these discussions were largely absent in the study of economics. One source of inspiration was the little book “Ethics and Economics” by Amartya Sen, later a Nobel laureate.

Almost by accident, Ellingsen began to explore this field. When he was teaching economic organization theory, he found evidence for the contention that traditional economics alone cannot explain how people make economic decisions. It is customarily assumed that people are rational, selfish and materialistic. But in reality, people often behave differently.

“My students challenged established theories, for instance how people behave in negotiations, which was a valuable eye-opener.”

My research has derived inspiration from classical thinkers in moral philosophy such as Cicero and David Hume. Their work continues to be of theoretical importance and offers much from which we can learn.

When Ellingsen was unable to provide satisfactory answers to his students’ questions, he realized that new research was needed. It was necessary to confront theory with experimental evidence to gain a deeper understanding of how economic and social factors interact. This paved the way for some scientific studies in the intersection between contract theory and behavioral economics.

“At first, I focused on the individual’s psychology, but I became increasingly convinced that this did not provide a full explanation. The most interesting questions concern groups and how individuals relate to social culture as a whole.”

In his latest project Ellingsen wants to focus on our sense of duty and its role in society. This is in the context of new and interesting research findings. A study published in Science in 2019 describes how researchers in the US and Switzerland studied how people in different countries react when they find a wallet containing money. The findings reveal huge differences from one country to another.

“In Sweden, for example, eighty percent of the wallets were returned, whereas in China, the figure was only twenty percent. And it seems that these differences are related to morals and culture that impact people’s behavior in various ways.”

The study also shows that wallets that contained more money were more often returned, contrary to what might be expected.

“It suggests that people may feel a greater duty to act fairly when the stakes are higher.”

It is difficult to give an unequivocal explanation for the results, but there probably exists a form of universalism and tolerance in the countries where people are more honest, Ellingsen says.

“It may have something to do with political stability and religious background, as well as what children learn in school – whether they learn to respect and tolerate other people, for instance.”

Several clues may emerge from the current project. Ellingsen hopes to use Swedish data to identify how a sense of duty impacts individuals in the workplace.

“We have fantastic data in Sweden, which means I can gather information on how dutiful different people are. I don’t know their identity of course, but it’s possible to measure various individual behaviors, such as whether or not they voted, for example.”

Once a measure has been obtained showing how dutiful people are, it will also be possible to study the correlation between a variety of parameters, including choice of career, wage levels and work ethic.

“It’s interesting to see whether those individuals who have a greater sense of duty also have more independent jobs or earn more.”

Working from home was common during the Covid pandemic. Since then, there has been an ongoing discussion about the attitude of employers to distance working. Ellingsen wonders whether remote work might be a better approach in societies with a higher level of reliability:

“This is a topical issue that can be examined in the light of our research.”

Ellingsen also wants to incorporate insights from other fields. One example is a collaboration with lawyers with a view to developing better contract drafting.

“Imagine a complicated construction project in which efforts are made to include loyalty to the project itself in the contract instead of trying to describe how all disputes are to be resolved. The focus will then be on formulating common values and a common goal.”

Ellingsen hopes that his research will be of future use to decision makers, businesses and society as a whole.

“Ultimately, it’s about understanding the role played by ethics in creating a functioning society. Our research highlights the role played by ethics in economic processes, thereby help to achieve societal gains if people in politics, trade and industry become better at seeing and understanding these mechanisms.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström