On average, people are living longer and healthier lives, but this goods news does not apply to everyone. People with higher education are healthier. Wallenberg Academy Fellow Johanna Wallenius is exploring welfare challenges of the future, including the growing health inequalities in society.

Johanna Wallenius

Professor of Economics

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, prolongation grant 2019

Institution:

Stockholm School of Economics

Research field:

Macroeconomic relationships between employment and formulation of economic policy, focusing on pension systems, family policy and higher education.

Wallenius is a professor of economics at Stockholm School of Economics. In recent years she has instigated research projects on themes such as pensions, family policy, and health and inequality – topics of great importance in the welfare context.

“We’re studying major demographic trends using advanced models and simulations, but the most rewarding aspect is that our studies are highly relevant to future economic policy.”

The findings can provide an important contribution to public debate, and hopefully serve as a basis for potential policy reforms.

“I’ve been invited to speak about my research by both the Swedish and the Finnish finance ministries.”

“The Wallenberg Academy Fellow scheme gives me a fantastic opportunity to meet smart and driven researchers who are at roughly the same career stage as I am. This makes it easier for me to transition into a more senior research role. The generous funding also enables me to devote much more time to research.”

Different pathways to pension

One premise for the research is the ageing population. People in the developed world live longer than ever, but they are also having fewer children. This poses a major future challenge for public finances. According to the EU Commission Ageing Report, by 2060 there will be one pensioner for every two people working, instead of the present one for every four.

One possible solution is that people work more and for longer. Wallenius has studied various factors that influence people’s desire to retire. One conclusion is that a carrot is better than a stick when it comes to incentivizing people to continue working.

“A robust pension system should be based on the premise that continuing to work yields financial benefits.”

Wallenius has chosen to compare the Anglo-Saxon countries, the Nordic region, and Central and Southern Europe. There are many routes to retirement. Some countries have very generous pension systems, and people can retire at a fairly young age. It may be more difficult to qualify for disability benefits in those countries, however.

In other countries there are fewer ways of retiring early. This can have unforeseen consequences.

“The result may be that people are encouraged to claim various forms of welfare. It’s important for politicians to consider this when they design social security systems.”

Single people face a poorer old age

Different life choices impact welfare as people approach old age. People living alone run a greater risk of ending up in poverty, whereas those who are married or living together can usually look forward to greater financial security.

Some countries, such as the U.S., have pension systems based on marital status. Wallenius elaborates:

“Marriage in the U.S. can almost be seen as a way of insuring against poverty. Pensions are tied to both spouses, and can be increased by the other spouse’s income.”

But research has shown that marriage or cohabitation seems to have a favorable effect on people’s finances even in countries with individual-based tax and pension systems, among them the Nordic countries.

Single-person households have a tougher situation. Wallenius has observed some worrying tendencies. Increasing numbers of children are now growing up in single-parent households, often in strained circumstances.

“Risks faced early in life have persistent consequences. We’re now trying to find out whether other welfare solutions or labor or family policy reforms are needed to alleviate poverty.”

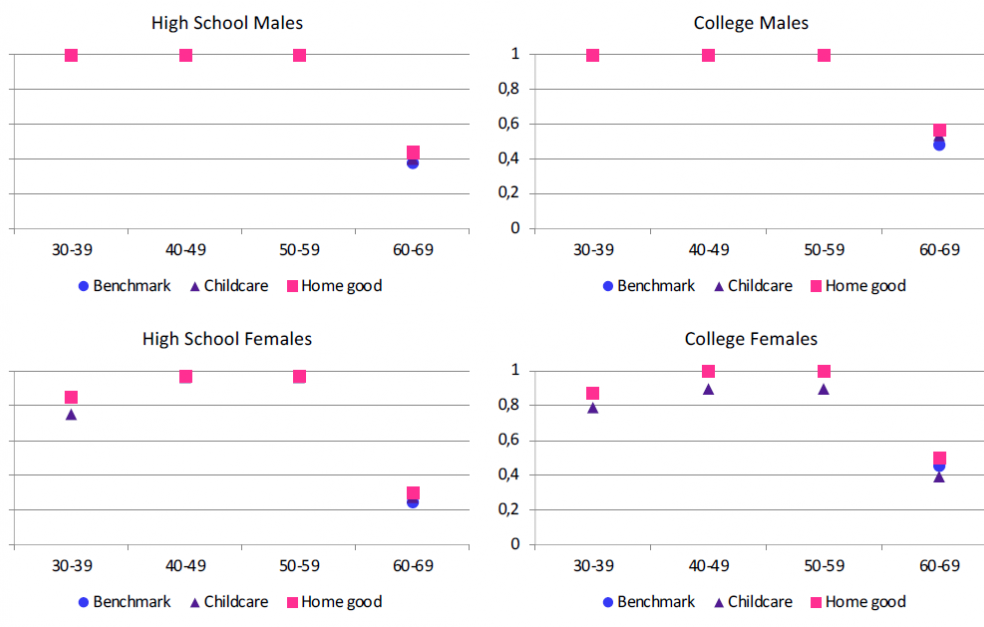

The link between health inequality and longevity is the focal point for another part of the research. On average, people are living longer and healthier lives – a positive trend but the gains of which are unevenly distributed.

“The improvements in health and life expectancy are mostly seen among people with higher incomes and higher education. We want to learn more about the underlying socioeconomic factors.”

Higher education brings healthier choices

Part of the project concerns the U.S., where private welfare solutions dominate. The same socio-economic gaps in health and life expectancy can be observed in countries with generous publicly-funded insurances systems.

“It’s been established that unequal access to health and medical care makes a difference, but that it is only one piece of a larger puzzle.”

Her findings suggest that education is a more important factor than many people think. Education impacts people’s lives in many ways: from knowledge to choice of career, salary and lifetime income.

“Highly educated people have greater opportunities to invest in their health. They invest more in exercise and preventive health care, have medical check-ups more regularly, and are able to buy healthier food. They’re also more inclined to follow their doctor’s recommendations, for example to change lifestyle or undergo complicated treatment.”

Wallenius sees a clear link between educational level and investment in personal health. This may be why countries with widely disparate welfare systems display similar socioeconomic inequalities in human health and longevity.

“Now we’re wondering whether it wouldn’t actually be more cost-effective for society to invest more in education than in health and medical care. This is an angle we want to examine thoroughly over the next few years.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Tuure Tuunanen