Over the past few decades the number of listed companies has fallen sharply in the U.S. as well as Europe. Shrinking stock exchanges have caused concern among policymakers at the highest level, but we still do not know much about the socio-economic implications. Wallenberg Scholar Alexander Ljungqvist is studying the phenomenon, and its impact on investors, consumers, and savers.

Alexander Ljungqvist

Professor of Financial Economics

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Stockholm School of Economics

Research field:

Financial economics, particularly the socio-economic role of the stock market

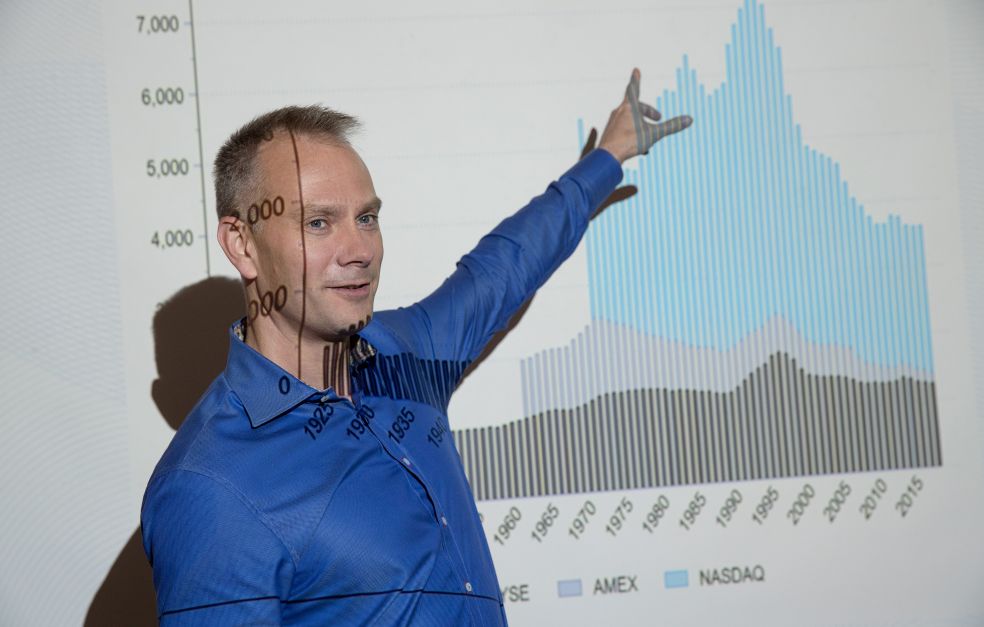

The number of listed companies in the U.S. has halved over the past 20 years, and Europe has seen a decline of about one-third. The reasons are open to debate but may include an increased regulatory burden. Ljungqvist, who is a professor at the Stockholm School of Economics, elaborates:

“One reason may be that some companies consider a listing too costly and cumbersome, perhaps because of tougher regulations on insiders and information disclosure. Another reason may be the creation of alternative sources of capital, such as private equity funds and the like, allowing companies to raise capital without going public.”

Whatever the underlying reasons, the fact is that stock markets are shrinking. But the decision not to list a company is not just a matter for its owners. Ljungqvist believes the phenomenon may have broader socio-economic implications.

“There are several groups that could be impacted, which is something I want to study as a Wallenberg Scholar.”

“The grant received as a Wallenberg Scholar is a luxury in the research world. It provides the long-term funding that is essential for us to be able to carry out a unique infrastructure initiative in the field of financial economics.”

Less access to information

The first category that Ljungqvist plans to study is investors. Investors are constantly on the lookout for information, and the more companies that are listed, the richer the information in the market. The information a company discloses helps investors to value not only the company in question but also other, similar companies.

“But when the amount of information available in the market shrinks, it may be more difficult for investors to value other companies.”

Consumers may also be impacted by the ongoing decline in the number of listed companies. The connection is not as far-fetched as it sounds. One factor is competition between companies. If innovative start-ups allow themselves to be bought up by giants such as Facebook or Google instead of listing on the stock exchange and raising capital that way, the likely result will be less competition in the market.

“A greater number of independent innovative companies listed on the stock market would likely give consumers more choice and better prices than if the companies let themselves be bought up.”

Harder to invest in ground-breaking sectors

A third category that Ljungqvist plans to study is that of savers. The concern is that it may become more difficult for the public to gain access to attractive investment opportunities.

“Anyone can buy securities listed on a stock exchange. The public has maximum access. But if companies are privately owned, they are only available to a privileged group. Neither you nor I can buy stock in a Silicon Valley start-up, for example,” Ljungqvist points out.

This issue is much debated at the moment, and researchers see new types of problem as innovative technology sectors grow.

“Let’s say that AI becomes a major force to be reckoned with in the economy. We economists would be happy to see savers being able to take out a kind of ‘insurance’ to cover the risk of losing their jobs, namely by investing in companies focusing on artificial intelligence.”

Saving in this way could, to some extent, compensate for future job losses. But if companies in these innovative sectors do not list, the opportunity to insure in this way is much diminished.

But Ljungqvist is not judgmental about companies’ choices. The aim of his research is to gain a better understanding of the stock market’s role in the economy and to make a contribution to the policy debate that is already underway.

“Decision makers in the political arena and financial regulators are concerned about the shrinking stock exchange and are considering what action to take. But in my view, there is a risk of rushing to judgments. First, we have to find out whether this is a socio-economic problem, which is why my research may play an important part in the policy debate.”

Back from the U.S.A.

The data for these projects will be obtained from U.S. sources, whose quality Ljungqvist says is better than that of European databases. Also, the trend has progressed much further there. He is well acquainted with the U.S. stock market after many years in America, among other things as a professor at the Stern School of Business at New York University, and as a member of the Nasdaq Listing Council.

In 2018, Ljungqvist moved back to Sweden, having been appointed to the Stefan Persson Family Chair in Entrepreneurial Finance at the Stockholm School of Economics. The following year, he was chosen as a Wallenberg Scholar – only the second economist to receive the honor. He will now have a unique opportunity to introduce new research approaches into economics. One example is a research lab inspired by the natural sciences, with standardized procedures and the highest conceivable standards of transparency and research ethics.

“We will be able to employ full-time assistants who devote all their time to research. Hopefully, this will be a model that can be used by others.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström