Dogs, too, can develop cancer and immunological diseases. With that in mind, Kerstin Lindblad-Toh began to research into dog disease genetics to find out how this knowledge can be applied to humans. Her goal is for the new findings to translate into personalized diagnostics and health care.

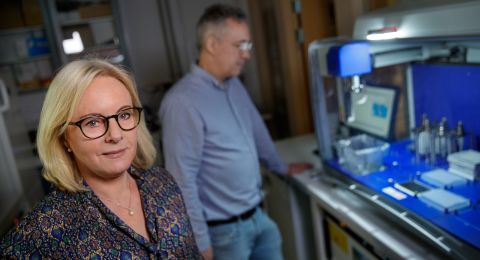

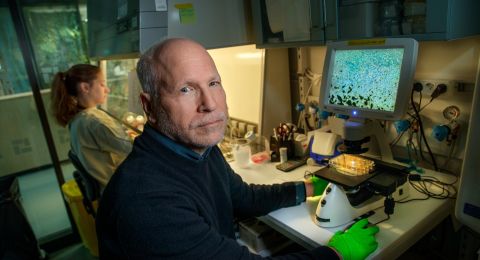

Kerstin Lindblad-Toh

Professor of Comparative Genomics

Wallenberg Scholar

Institutions:

Uppsala University and the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT

Research field:

Disease genetics in mammals and humans

Lindblad-Toh has long been at the global forefront of developments in genetics. As far back as the 1990s she began to study the genetic relationship between mice and humans as a postdoc in Boston. And her research took on a momentum all of its own. To date she has been in charge of sequencing the genomes of more than 150 mammals – large-scale projects that have advanced the boundaries of science.

“When we see which parts of the genome are common to all mammals, we will have a better idea of which parts are also important in the human genome. Most pathological mutations take place in the parts that are the same in all mammals,” Lindblad-Toh explains.

She is now devoting her energies to a major initiative on disease genetics in dogs and humans, made possible by the Wallenberg Scholar grant and a project grant from the Foundation. The aim is to integrate genetic research with the health care sector.

“We can use the dog as a model for understanding various diseases. Dogs often develop diseases akin to those affecting humans, such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and immunological diseases,” Lindblad-Toh explains.

One reason for this is that dogs and people live in the same environment and share the same lifestyle. But the fundamental explanation lies in selective breeding by humans.

“Over the past hundred years or so we have bred a multitude of dog breeds for desired characteristics and behaviors. Some traits are hidden and are passed on – some of them also cause disease.”

“The Wallenberg Scholar grant means a lot. It is of course an acknowledgement that our research is of a high quality, but it also offers new opportunities to try out ideas as we pursue our goal of bringing the human genome all the way from basic research to the health sector.”

Immunological diseases

Among other things, Lindblad-Toh is studying the genetics behind immunological diseases. She mentions SLE, a rheumatic disease in which the immune system attacks joints and organs, potentially causing intense suffering:

“The impact of the disease varies. During some SLE episodes the patient may be very ill indeed and may even suffer organ damage. Sufferers must also live with long-term problems caused by the disease.”

The wide variety of symptoms, including light hypersensitivity, kidney problems and lung damage, suggests that the underlying genetic causes are complex.

“We want to understand the interrelationships involved,” says Lindblad-Toh.

The researchers are using gene mapping methods on multiple dog breeds to create a map of relevant disease genes. So far, they have found disease genes for SLE, eczema and thyroid disorder, and have also identified several areas of canine DNA that are associated with disease.

Mapping patient DNA

Lindblad-Toh and her fellow researchers used the canine studies and a review of scientific articles as a basis for selecting just over 1,800 candidate genes. A study was then designed in collaboration with clinics throughout Scandinavia. The aim was to collect samples from patients with diseases such as SLE, Sjögren’s syndrome, myositis and Addison’s disease.

“We have collected as many samples as we possibly could in Sweden and supplemented them with material from Norway and Denmark. It is more usual that the same pathological mutations are found within a homogeneous population, as in these countries.”

The researchers sequence patient DNA and compare it with various control groups, such as elderly and healthy people. Sometimes they strike pay dirt.

“We have found many extremely interesting mutations with a regulating role, controlling when, where and how much protein is synthesized,” says Lindblad-Toh.

Paving the way for personalized medicine

The new discoveries describe previously unknown genes for several diseases, including SLE, and regulation pathways and groups of genes with a similar function. The findings will be used to identify sub-groups of patients, and find genetic risk factors capable of identifying people who risk developing various complications.

Lindblad-Toh says it represents another step toward personalized medicine:

“We’re hoping to be able to predict whether a given individual will develop the disease – and an enhanced understanding of the genetics may also enable us to say how the individual will be affected, perhaps in their lungs or in some other way.”

The researchers also hope it will be possible to help people suffering from unknown immunological diseases, where clinical diagnoses currently remain elusive.

“Ideally, there should be a clear genetic diagnosis for patients with an unknown disease, with a simple procedure for informing a relative that they may be at risk of developing a disease. And of course, we must be able to design specific therapies.”

Lindblad-Toh has been involved in establishing two scientific hubs: SciLifeLab in Sweden and the Broad Institute i USA. She spends part of the year in Uppsala and the remainder in Massachusetts. She thrives in these international environments and the inspiring networks that bind them together.

“Our strength lies in endeavoring to collaborate as much as possible, and in our desire to address the major questions concerning the cause of disease. Interdisciplinary collaboration is essential and is the reason I want to work in both places.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Mikael Wallenstedt, Magnus Bergström