Project Grant 2018

Deciphering the role of functional constraint and convergent evolution on genome regulation

Principal investigator:

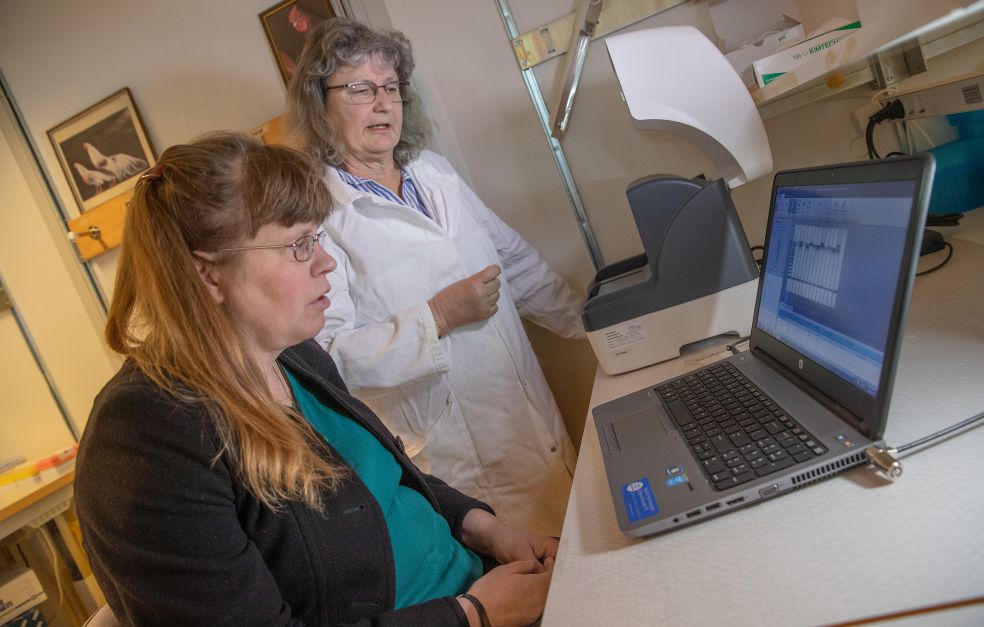

Professor Kerstin Lindblad-Toh

Co-investigators:

Karolinska Institutet

Patrick Sullivan

Institution:

Uppsala University

Grant in SEK:

SEK 28.1 million over five years

The “man’s best friend” proverb is ascribed to King Frederick the Great of Prussia in the 18th century. By then dogs had already served as beloved pets and been put to use for hunting and as watch dogs for thousands of years. The oldest skeletons of domesticated dogs can be traced back to the Stone Age.

The multimillennial relationship between humans and dogs is reason enough to study similarities and differences between dogs and humans. Many dog breeds suffer the same kind of diseases as humans – cancer and cardiovascular problems, for example. But only now, thanks to modern-day large-scale DNA research, has it become possible to detect pathological changes in DNA.

Kerstin Lindblad-Toh is Professor of Comparative Genomics at Uppsala University, and heads a research project funded by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. She is sifting through enormous quantities of data in search of patterns to improve our understanding of the DNA.

“If we can find mutations in the DNA that give rise to different characteristics, our work may ultimately contribute to the development of new and better drugs.”

Focusing on the brain

Lindblad-Toh is one of the pioneers of international genome research, leading a team that mapped mouse and canine DNA as far back as the early 2000s. It was then that she realized that the dog could serve as a disease and behavioral model – and now the technology has caught up with her.

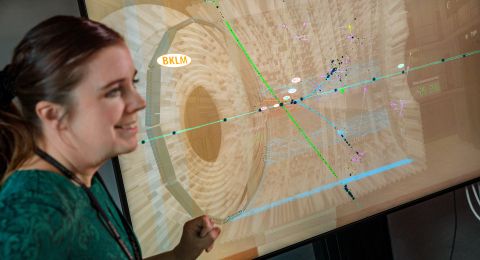

“We’re finally reaching a point where we can compare genetic and physiological aspects of brain function in humans and dogs.”

At present the mouse brain is often used as a disease model, but it is much smaller than the human brain. The researchers hope that detailed mapping of the dog brain will provide radically new insights.

“We believe that the canine brain is fairly similar to that of humans. Dogs are social animals, and are capable of interacting and communicating. We are using new methods, such as single-cell analysis, to study different parts of the cerebral cortex, which is involved in decisions governing interaction and behavior.”

Fast track to medical research

The dog can be used as a fast track to a better understanding of human diseases. Data from hundreds of thousands of patients may be needed to find genes regulating schizophrenia or depression, whereas it may only require hundreds or just a few thousand individuals to make equivalent studies of dogs.

One reason that many common diseases also affect dogs is their close association with humans. Dogs have been bred strictly in order to achieve certain perceived ideal characteristics. But selecting a gene to achieve a given appearance or behavior can sometimes impact other tissues in the body, potentially causing cancer, for example. Another explanation may be that human interference has compromised the ability of natural selection to eliminate bad mutations, instead preserving, and even accumulating, disease genes in dogs.

“Many of these diseases have genetic causes – there has been an accumulation of certain variants that are not much good for survival, but have some other desired characteristics in terms of appearance or behavior,” Lindblad-Toh explains.

There are already results identifying genetic risk factors for conditions such as OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder), and SLE (systemic lupus erythematosus), an auto-immune disease in dogs, which can also affect humans.

“We are grateful that there are so many dog owners who want their dogs to take part in our studies, even though the situation can take a heavy emotional toll. A central part of our job is also to achieve results that can lead to better diagnosis and treatment methods for dogs with diseases.”

Mapping DNA in hundreds of mammals

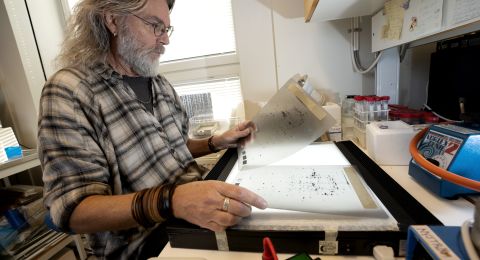

Aside from the canine studies, Lindblad-Toh is involved in mapping the genomes of many other animals. In recent years her lab and collaborators have put together a dataset of ~250 sequenced mammals. Huge quantities of data are now being processed so that comparative studies can be made.

The researchers are concentrating particularly on areas of DNA that have remained intact throughout the evolutionary process – some 10 per cent of the entire genome. But they are also studying areas that have changed extra rapidly in dogs or humans. They want to identify DNA regions that are particularly important for certain behavior or diseases.

“This is where a difficult job gets even trickier – we have to understand exactly which letters in the DNA are functional. Say that we find a region outside a gene, and see ten separate mutations, but we don’t know which ones cause the disease. This is one of the tricky problems we often have to deal with.”

One solution is to study data from functional genomics in the canine brain to see which genes are switched on and off in different parts of the brain. This involves painstaking detective work.

“We’re trying to take something to pieces and examine every minute piece of the puzzle, which isn’t always easy when you’re keen to do many things at once,” Lindblad-Toh says, laughing.

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström