Project Grant 2016

Arctic Climate Across Scales

Principal investigator:

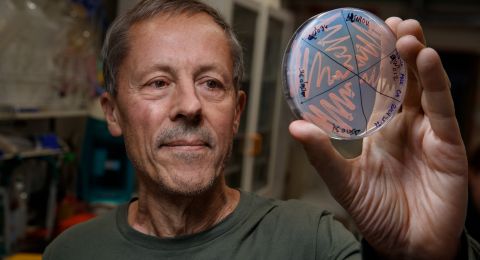

Michael Tjernström, Professor of Meteorology

Co-investigators:

Annica Ekman

Gunilla Svensson

Hans-Christian Hansson

Ilona Riipinen

Johan Nilsson

Radovan Krejci

Rodrigo Caballero

Institution:

Stockholm University

Grant in SEK:

SEK 29.9 million over five years

Michael Tjernström, who is a professor of meteorology, has been on several research expeditions to the Arctic. In summer 2018 he is headed for the Arctic Ocean surrounding the North Pole. This time Oden, a research vessel and icebreaker, is carrying equipment to gather meteorological data.

“On board Oden we will be heading into the ice north of Svalbard, to somewhere far to the north where we will find an ice floe and moor to it, then letting the ship drift with it for five weeks.”

Thanks to project funding from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, Tjernström and his fellow researchers at Stockholm University will begin to realize their vision of a permanent observatory on Oden that will provide observations also from future expeditions undertaken by other scientists.

“Numerous observations of meteorological processes are made in most climate zones, often from permanent observatories, but less from the Arctic and hardly any from the Arctic Ocean. This is of course because the Arctic is as it is – there is nowhere to set up permanent instruments. The ice is constantly on the move and breaks up. Sooner or later the equipment ends up in the water. Accurate monitoring of processes simply has to take place from ships, from icebreakers.”

Temperatures rising faster in the Arctic

Reasons for the project are the international climate convention signed in Paris in 2015 and the special sensitivity of the Arctic climate. Under the convention, countries must work to keep the rise in the global average temperature below 2 degrees, and preferably below 1.5 degrees Celsius.

“Current climate change is most rapid in the Arctic. The rise in Arctic temperatures is between two and four times larger than the global average, depending on the time span measured. This means that if we use the worst-case scenario envisioned by the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), with a global temperature rise of just over 4 degrees Celsius by the end of the century, the warming will be 8–12 degrees in the Arctic. This will naturally have enormous implications for everything in the region.”

There is also a growing realization that events in the Arctic will have implications elsewhere. Tjernström explains that changes in the region will impact the global climate:

“Although there are many positive developments, CO2 emissions are still increasing, and we add to global warming with each day that goes by. This doesn’t mean there’s nothing we can do, but we must realize that the climate will not return to what it was for a very long time, even if we manage to radically reduce emissions.”

The overall question the project is intended to answer is what will happen to the summer ice in the Arctic if we manage to limit the global rise in temperature to two degrees. The uncertainty inherent in current computer models is the key to the project. Tjernström elaborates:

“The Arctic as a system is characterized by its perennial ice. True – some ice melts every year, but some multiyear ice remains at the end of summer. So the entire ecosystem, with its unique plants and animals, and traditional way of life for communities hunting seals and whales from the ice – all this is dependent on the presence of the permanent sea ice. According to our current calculations, summer ice will disappear completely sometime after 2050, although there is much uncertainty about exactly when this will happen.”

Chain of processes

Tjernström explains that when large quantities of warm air enter the region in spring, the snow overlying the ice starts to melt much earlier. This darkens the surface, and when the sun brings real heat in the spring and summer, less sunlight is reflected, and the ice melts even faster.

Eight climate researchers and their teams are collaborating in the project. They hope that more detailed knowledge of three interlinked processes in Arctic systems will improve the accuracy of climate models: how the Arctic is impacted by changes in large-scale atmospheric weather, how clouds are formed in the area, and how energy is exchanged between the ocean, ice and atmosphere.

“We want to understand the entire chain – from large-scale weather to the ice melting.”

Sources of the meteorological information collected on board Oden include radar and lidar (light detection and ranging), which entails sending out signals that measure what the atmosphere bounces back. But much of the monitoring also uses conventional techniques such as weather balloon soundings. The first year after an expedition is spent ensuring the quality of the data and converting it into something that can be understood and analyzed.

“We want to be able to create a refined digital copy of reality in the Arctic in our computers. All data will also be shared with other research teams around the world. Our project is also part of a larger ongoing project called Year of Polar Prediction (YOPP).”

Text Susanne Rosén

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström

Facts about the Arctic:

The Arctic is the area surrounding the North Pole. Cold winters and cool summers typify the Arctic climate. Some four million people live in the region. Many of them belong to the forty or so indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic. The Arctic environment is unique. Much of the flora and fauna is endemic and depends on ice and cold conditions to survive.

In recent decades, and particularly in the 1990s, the definition of the Arctic has been widened and has acquired more political connotations, partly independent of climate and vegetation. According to that definition, the Arctic region comprises the Arctic Ocean, all of Iceland, Greenland and Alaska, as well as the northern areas of Canada, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia.

Source: Swedish Polar Research Secretariat, and Wikipedia